The Darien Gap, a dense jungle connecting Colombia and Panama, has become a deadly route for migrants seeking to reach the United States. Entire families, including young children and babies, face the unforgiving nature and constant danger of violence on their journey.

A record number of migrants – 520,000 – passed through the area in 2023. Almost 280,000 have crossed this year as of Oct. 7, according to the Panamanian Ministry of Security.

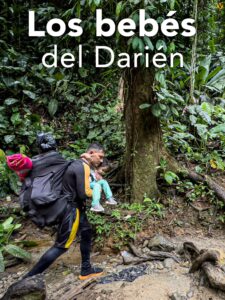

José Guarnizo published a report concentrating on the vulnerable children who migrate across the Darien Gap. (Photo: José Guarnizo)

While news of the Darien often reaches consumers around the world from foreign correspondents from large media outlets, journalists from Panama and Colombia specializing in migration are providing critical reporting on the region.

José Guarnizo, cofounder and general director of Colombian news site Vorágine, has witnessed human tragedy in the Darien since 2009. He said what drives him is not only documenting the physical dangers of the jungle, but also capturing the stories of those who traverse it.

With 18 years of experience covering human rights and migration, he has returned to the Darien again and again, each year finding new voices, new faces and new tragedies.

“What matters to me is capturing the characters in the best possible way. I want to know their stories and I try to go with them on the journeys as far as I can,” Guarnizo told LatAm Journalism Review (LJR).

In 2023, he published a special report about “the most vulnerable” people making the trek: children and their mothers.

“Every year, the Darien claims lives,” Guarnizo said. “Desperate mothers, children who don't survive the crossing, families left separated in a terrain where life is worth little.”

Despite the risks, Guarnizo always finds someone willing to share his story. The most important thing, he said, is to “build trust.”

“Ask first what they need at that moment, and what I can help them with, and do it in a genuine way. From there, trust is built,” Guarnizo said.

That connection is what drives him to return to the jungle, again and again, although he admits it's not always easy to leave behind the people he meets along the way.

“You even have a hard time letting people go sometimes,” Guarnizo said.

Grisel Bethancourt, a Panamanian investigative journalist with more than 20 years of experience, has witnessed the radical changes of the Darien.

What was once a quiet region of Indigenous communities is now a forced passage for thousands of migrants every day, an area where migration and drug trafficking have profoundly altered the lives of locals.

Bethancourt began covering the Darien from another perspective: the rights of children born from guerrillas who were not recognized as Panamanians.

Soon, however, her focus broadened to understand how the massive flow of migrants was affecting Indigenous communities.

One of the places that left the biggest mark on her was Bajo Chiquito, a small Indigenous village in the middle of the jungle.

“What was once a small village with wooden houses now has multi-story cement structures,” Bethancourt told LJR.

Panamanian investigative journalist Grisel Bethancourt has witnessed the profound changes of the Darien Gap. In 2023, she concentrated on the village of Bajo Chiquito for a bilingual report published by newspaper La Prensa and transnational investigative network CONNECTAS. (Photo: Grisel Bethancourt)

Her reporting shows the transformation of this community where ancestral traditions have been replaced by an economy based on the business of migration. In her article, she tells how goldsmithing and basket-making were traded for working in restaurant management, internet service shops and currency exchange offices.

“The Indigenous communities have left many of their customs behind, and everything is driven by money,” Bethancourt said. ”Seeing how young people have abandoned farming and fishing for the modern clothing and electronic devices that now control their lives.”

Bethancourt recalls nights in the jungle when the darkness is filled with illegal activity.

“The lack of intervention by Panamanian authorities has perpetuated extreme poverty,” she said.

Drug trafficking and sex work thrive under the light of the moon, and local criminals control the economy, according to Bethancourt’s reporting. Migrants, exhausted and often robbed of everything, arrive in these towns looking for help, but face new struggles to survive.

Both Guarnizo and Bethancourt have experienced the risks and emotional drain of reporting on the Darien.

“I couldn't sleep the first night. The pain of seeing people destroyed by fatigue, swollen feet, children arriving alone without their parents... that marks you forever,” Bethancourt said.

Grisel Bethancourt, far right, conducts interviews in Bajo Chiquito. (Photo courtesy Grisel Bethancourt)

Guarnizo said his journeys covering the Darien usually last about a day and a half. He doesn’t cross the border – just accompanies the migrants there and returns home. He points to the risks covering the migration zone, including robbery and harassment.

Yet, he said, “A story is not worth anyone's life.”

He knows that walking through those jungles is dangerous, but also that those stories must be told.

In the middle of so much darkness, both journalists find a point of light. Guarnizo speaks of the strength and hope that persist among migrants.

“Even in the hardest stories, you find something positive, because not everything is black and white,” Guarnizo said.

And Bethancourt, despite the challenges, sees her work in the Darien as one of the most significant opportunities of her career.

“Journalists have many opportunities, but this has been one of the most important to demonstrate the rigor and quality of journalism in Panama,” she said.

*Desiree Marquez, the author of this article, is a bilingual journalism undergraduate student at the University of Texas at Austin. Originally from the Juárez-El Paso border region, she has a passion for storytelling and is enthusiastic to contribute her skills in writing and communication in a variety of platforms.