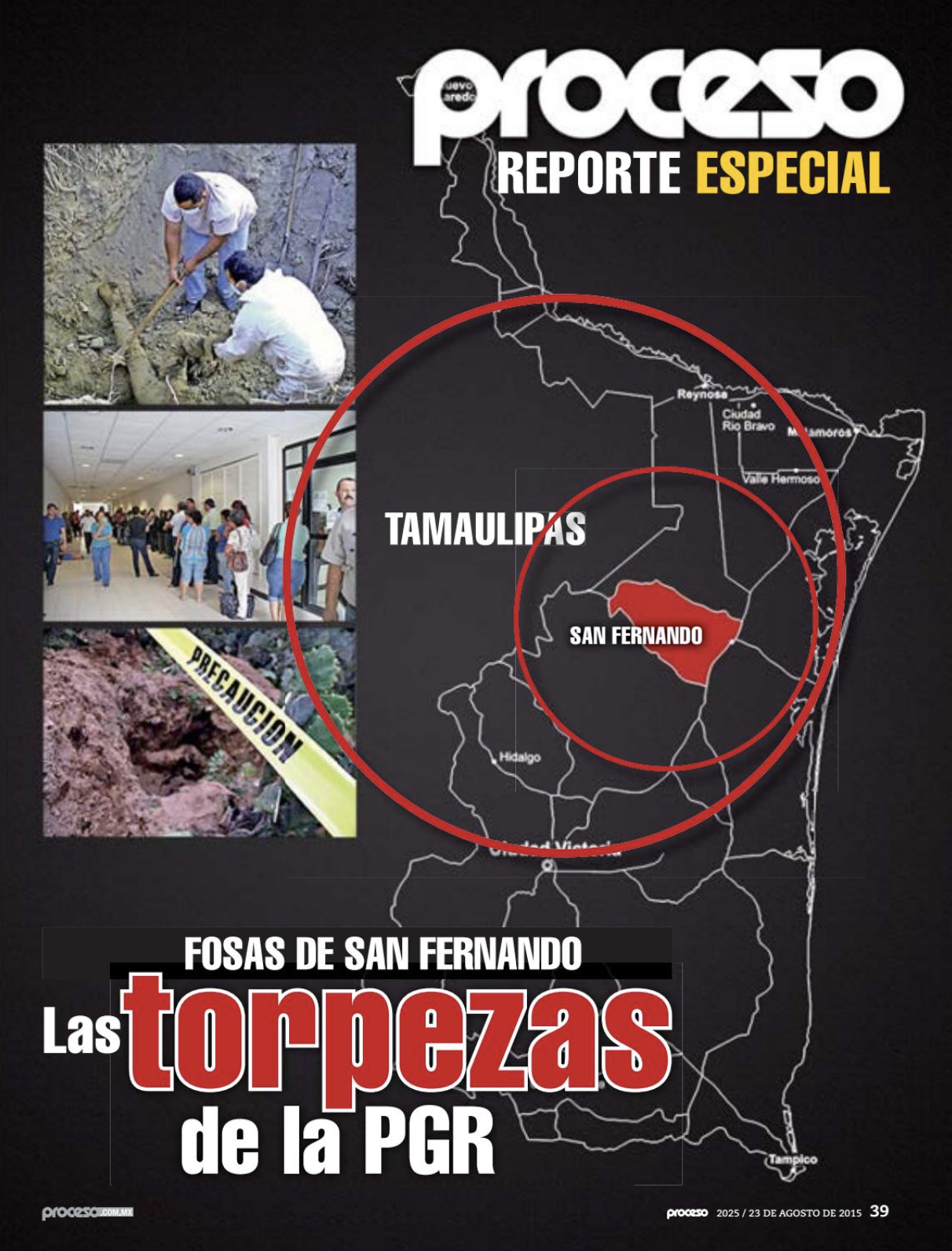

The municipality of San Fernando, in the state of Tamaulipas, about 93 miles from the northern border of Mexico, was the scene of two crude acts of violence last decade. The first, in August 2010, was the massacre of 72 migrants, most of them Mexicans and Central Americans, who were taken off the buses in which they were going to try to cross into the United States and then were tied up and murdered.

The second was the discovery, in 2011, of 47 clandestine graves with almost 200 bodies, which hinted that the massacre a year earlier had not been an isolated event.

Although the Mexican government recognized the events and blamed the Zetas cartel, journalists and organizations have denounced that authorities not only failed to investigate potential complicity of officials, but also “re-disappeared” many of the bodies with deficient forensic procedures, the incorrect delivery of bodies and the concealment of information, which prevented relatives from identifying missing loved ones.

Turati was allegedly spied on, and confronted fears and obsessions during her investigation on the violence in San Fernando, in the state of Tamaulipas. (Photo: Mary Kang/Knight Center)

Both events represented a turning point in the career of Mexican journalist Marcela Turati, who in 2011 was sent by the magazine Proceso, where she worked as a reporter, to cover the discovery of the graves.

Upon arriving in San Fernando, she encountered a horror that marked her for life, but also a series of injustices and irregularities that the press was not covering in depth and that became a kind of professional obsession for the journalist.

More than 12 years later and after hundreds of hours following clues, carrying out dozens of interviews and reports, and producing several collaborative projects, Turati released "San Fernando: Última Parada" (San Fernando: Last Stop) in 2023. It’s a book that presents a multi-character narrative about those horrific events to which she has dedicated more than a decade of her career.

The journalist shared with LatAm Journalism Review (LJR) her experience and lessons learned from carrying out her editorial project, in a country where, she says, the press has the challenge of learning to better cover and tell stories of the disappearances of people and organized crime – issues in which Mexico has record numbers.

This interview has been edited for length and clarity.

LJR: What do you think the press has done poorly in its coverage of the disappearance of people in Mexico?

Marcela Turati: I wouldn't blame the press. Yes, we have 111,000 disappeared people, we have media outlets that are not interested in this topic because it does not translate into clicks, because many people don't want to know. So we have a very big challenge, which is how we tell it. We also have a lack of training for journalists. We often stay in the anecdote and it is difficult to find a more social focus, because the articles with testimonies are more impactful than the articles that tell you how the system operates.

I always thought that there were no journalists in San Fernando, but obviously there were, but they have been silenced for many years. Journalists were also under threat, like many people. Interviewing people in a silenced area is very complicated. Having any information is very dangerous.

So I wouldn't put the burden that the topic is poorly covered on journalists, because they have many jobs. Those that I see who are still dedicated to the topic of disappearance are journalists who are committed to it, who make time for it in their free time because they need the families to be heard.

LJR: Why did you decide to write a book for this complex 12-year investigation?

MT: There were things [from the investigation] that I kept for myself, that I couldn't publish in the magazine Proceso, things that were very cruel or very hard to explain to the reader. In four pages you cannot tell the cruelty with which these people were murdered, because they were not shot to death, their torture was very harsh. That was one of the things that I preferred not to publish in Proceso, because it seemed to me that in a story I was only going to horrify people, but no one was going to understand anything.

I also had a lot of interviews, but with people I couldn't even name and for whom it was still dangerous to talk, so I started collecting and collecting information. There came a time when I said: “all of this cannot be published like this, loosely.” I had a lot of things and I said: “I'm going to start making a book.”

I was thinking: “How do I give it a narrative structure?” I was stuck. But at one point I said: “this has to be a multi-character narrative.” I already had so much time, so many testimonies, that I said: “this cannot be told by a single character.” There are many passages, it’s 12 years, they are different locations, not everything happened in one place. Then I started making a collage by theme, like layers of an onion.

The book is a chorus of voices, there are monologues, too. I just wrote an introduction and people read what everyone in San Fernando experienced. Or what happens to the families of victims who search for their relatives and everything they experienced in their searches.

"San Fernando: Última Parada" is a multi-character story of the massacres of migrants in the state of Tamaulipas. (Photo: Courtesy Penguin Random House)

LJR: How did you collect those testimonials?

MT: I worked at the magazine Proceso, so I followed the issue if I knew that relatives of the massacred migrants were coming, or if I knew that an organization had contacted some of the families of the people found in the graves. I was in [the organization of investigative journalists] Periodistas de a Pie and had called for the founding of a collective called Más de 72 to carry out investigations and follow this news. We did a first investigation into what the massacre of the 72 was like and we began to see that the government was lying, that it had invented things that did not make sense and we made a website of all these facts.

Then I did a second part with some students. I asked them each to take a thematic line about the graves and we would investigate. This monitoring was so obsessive that I had to apply for several grants, one of them to process some forensic files that an anonymous source gave me in 2013, two years after [the discovery of] the graves. I also received information from people who realized that they had cremated several of the bodies that I was following up on. Then I was able, thanks to a grant with two other colleagues, to follow the path the migrants had taken, but in reverse, to go town by town asking for survivors, people who had information or who knew more about what had happened on those trips. There I began to notice irregularities, that very poor forensic work had been done, that the Attorney General's Office had lost bodies, that it had delivered incorrect bodies, that bodies that had been identified had disappeared and it had never notified their families.

I also partnered with the National Security Archive in Washington, which declassified some cables and gave me the information. Also here through [the National Institute of] Transparency in Mexico. There were many years of asking for information and taking advantage when the families of the victims came to Mexico, or that I could go to Honduras, Guatemala, or El Salvador, or to Guanajuato, Michoacán, or even enter Tamaulipas, to ask everyone who had some information that would tell me something. And from there, a clue led me to another person, to another, to another until I was able to write this book.

At Más de 72, we asked people on networks if they had more information. That's how people from Tamaulipas who were no longer afraid to tell me, to invite me to go, started writing to me. Also reviewing the documents, taking out the names of the officials who signed, or witnesses, all kinds of people, I tracked them down until I convinced them to give me an interview to understand not only from the victims, but also to understand from the government what happened in these cases and why they didn't prevent it, why they hid the bodies.

LJR: You were among the journalists who were spied on with the spyware Pegasus*. How did this affect your investigation?

MT: It wasn't just that incident of spying, there were two. When I published a story in Proceso where I mentioned that there were bodies that had been identified by the Attorney General’s Office, but that the Attorney General's Office had not returned them to their relatives and had buried them, or that they had cremated bodies of people and that they had been handed over incorrectly, that report triggered the Attorney General’s Office to investigate me. They requested all my calls from six months prior and asked the investigative area of the Federal Police for all the geolocation data from when I traveled, and who I spoke with. They analyzed how many of my calls had been with victims or with human rights defenders, and they also tracked me. They went to houses where I went. They wanted to know who passed me the information I had published. That was the first time I was spied on. And to do it without a judge's order, they invented an investigation folder, which [said that] I was suspected of kidnapping and organized crime in those graves. I was in the investigation folder of the same case I was investigating! I still am.

In 2016 and 2017 it was the Pegasus thing, when my name appeared on the lists [of people allegedly spied on]. I suppose that was because of the case [of the disappearance of 43 students in] Ayotzinapa.

I did notice very strange things, I noticed strange calls. People came to give me false information, or that I felt they were giving me false information. People came to tell me that they had disappeared relatives and I discovered that no, it was a lie. People came and told me they were Zetas, that they wanted to take me to show me where they had a grave. They also stole the hard drive from my computer, I had problems with the internet at home. We realized that my house's IP had pages like the Army's blocked, that we couldn't see certain pages.

It was very complicated because I didn't really know what was happening. I also didn't know for which case [I was being spied on]. That was a learning experience: not having dangerous investigations open at the same time, because then it is very difficult to know, from everything that happens to you, who the actors are, or who could be behind it. But for me it was clear that it was the Army** in the Ayotzinapa case and the Attorney General’s Office in the case of the graves.

[Editor’s notes:

*Turati’s name appeared on a list of journalists and others potentially targeted using Pegasus spyware. This was reported by a consortium that included investigative journalism nonprofit Forbidden Stories. After the release of the list, the NSO Group, which produces Pegasus, denied the allegations.

** President Andrés Manuel López Obrador has denied that the Army spied on journalists.]

LJR: Were you afraid?

MT: It was always complicated. I didn't even want to transcribe things because I was afraid that they were monitoring me. That's why I also carried a lot of hard drives and notebooks because I didn't feel like transcribing them. I felt that when it was time for me to write it down I could transcribe them, but not before. So that made it even more complicated. It was emotionally very hard.

The fear stopped me a lot, the fear that something would happen to people, the fear that I would reveal some identity, the fear that my files would be taken away, fear of the government, and my own fear that I wanted to continue investigating. Entering San Fernando also always made me very afraid, but I still went in to collect testimonies.

Prior to the launching of her book, Turati published in Proceso magazine numerous reports on the murder of migrants and the discovery of clandestine graves in Tamaulipas. (Photo: Proceso)

LJR. How did this investigation impact you emotionally?

MT: The issue of covering graves, seeing photos of bodies, meeting the families, seeing files, seeing photos of destroyed corpses, being in it all the time became very emotionally complicated for me. There were many moments of not wanting to know about the investigation, of not wanting to know if I wanted to publish it or if I had already forgotten about it. Until it occurred to me to send the book proposal to the Javier Valdez Cárdenas award. So, since I won, that made it clear to me that I had to finish it.

But I decided that the book was not going to be about what happened to me. Although I do reflect on silence, on the zone of silence, on the difficulty of finding truth in a place where pieces [of the puzzle] have disappeared, where authority does not want you to know, where it persecutes you, where it destroys evidence and constructs false evidence.

LJR: I imagine that it is not easy to let go of a topic for which, as you have said, you had an obsession. What's next for you as a journalist?

MT: I want to continue reaching out to different families and seeing how they can use the book for the cause of truth, to ask for justice.

On the other hand, I did a closing ritual. Rituals are important to me, that's what I also learned in this reporting process. What caused me obsession, what had inhabited me were the photos of these murdered young people, of their bodies. So I somehow made a ritual, talking to them, telling them that I already fulfilled it, that this was my goal, and that I hope they get justice. And emotionally I feel that in some way I am giving closure, handing them over to their relatives, presenting them.

It is time to continue talking about it, presenting it, because the book has many keys to understand what we are experiencing today in Mexico. It is not a story of the past, but many things continue to happen.

What follows is also taking some time of silence, of rest to be able to “reset” and change the subject. Take some time and then continue.

Workshops taught by Marcela Turati and her team as part of the project “A dónde van los desaparecidos” (Where do the disappeared go) aim not only to train reporters on how to better cover and report on the disappearances of people, but also how to create a network of journalists, provide support and help them mitigate risks.

Turati shared five main tips that journalists can apply when addressing the issue of disappearances in a journalistic investigation.

1. Follow up on leads

“From the moment you enter the first case, [you must] preserve the information, pay attention to everything. Always keep phone numbers, names, in case you have the chance to follow them. Always try to give it continuity.”

2. Establish a team security strategy

“You always have to try to be monitored, to have a team with whom you are working, with whom you coordinate and organize yourself to be able to establish a security scheme.”

“If you are going to release information to see if some people might contact you, make sure people who contact you are not part of a trap. You have to pay attention to the security measures, to see if you are going to contact these people.”

3. Stay alert to the topic during other reporting

“On each trip, do your normal day-to-day work, but also continue to advance the other topic, always keep it in mind wherever you are. Suddenly I found people who for some reason knew [about my investigation] and it was thanks to me mentioning it that, in the United States and other countries, I found many new sources that I had not thought of.”

4. Address the problem on a large scale

“I always say 'I wasn't so interested in whether the leader of the band was one character or another. I'm interested in understanding how the whole system works.' I am interested in understanding more sociologically how terror is established or how the Attorney General's Office operates."

“For me it is very important to reveal the mechanics of violence, that it not remain in anecdotes and that of horror, but that each story also has something revealing about how these logics of violence operate, without failing to point out what the State does, what it should have done.”

5. Point out the faults of the authorities

“There are many stories about drug traffickers or terror, but we have to put a magnifying glass on the response that the State should give, and check and investigate why it was not given and why people were left helpless. And then we also [must point out] the criminal attitudes of those who had to identify the bodies and did not do so.”