Four years ago, when the Colombian government signed the Peace Accords with the then Farc guerrilla, one of the fundamental issues was the attainment of justice and truth about what happened in the longest armed conflict in Latin America. This is something that has also been sought after by Colombian journalism which has investigated and intensely covered the 60 years of violence.

To narrate the armed conflict also means writing the country’s memory. If certain standards take place, it is a process that can bring dignity to the victims.

That is why, when the journalism site Rutas del Conflicto and the project La Paz en el Terreno handed their investigations and database over to the Commission for the Clarification of Truth, Coexistence and Non-Repetition, it undoubtedly turned into a historic act for the journalism in that country and as a way of recognizing its labor. A month later, according to Óscar Parra, director of Rutas del Conflicto, the outlet would be the first to officially give information to the Special Jurisdiction for Peace (JEP).

Both the JEP and the Truth Commission were created during the signing of the peace accords on Sept. 26, 2016 and again, after some modifications, on Nov. 24 of that same year. In simplified terms, the JEP is a tribunal in charge of judging the crimes committed in the framework of the armed conflict, while the Truth Commission's function is to clarify and give a historical explanation to the conflict in an in depth final report.

Screenshot of site Rutas del Conflicto.

On February of this year, the JEP contacted Rutas del Conflicto for the first time, Parra told LatAm Journalism Review*. The JEP was interested in the feature “Ríos de Vida y Muerte” (Rivers of life and death), a piece of journalism work that with the help of forensic techniques narrate the stories of missing people in rivers, as well as the bodies that appear in them: communities near rivers that find bodies and bury them in mass graves, families that look for their loved ones in rivers, places from which the bodies were thrown, among other acts.

“We have put in a great effort because it is unique, it is a hybrid of journalism and other things. When we did our reporting, we tried to find other technical elements that could facilitate the work of these entities,” Parra told LJR. “Besides telling the stories of the people around the area… we went and took a coordinate, we constructed a database and that mixed in with a bit of general history, from a journalistic standpoint.”

To get these geographic coordinates, the journalistic team had a forensic specialist. “All this is public information [on our site], but there is one that is structured in a database, so [the Jurisdiction] asked us if it was possible to access that information so that it could enter it into the JEP system and analyze it,” Parra said.

Even though the JEP looked specifically for information about the Magdalena River because it had solicited precautionary measures to protect one of the cemeteries in the area, the JEP asked the team of Rutas del Conflicto if they could turn over all the information on the site.

“It’s not very commun [for an outlet to turn over their data to an institution], but, well, we are very happy because if the information that we worked on can help in the future, wonderful,” Parra said.

1,500 records between databases and journalistic investigations

Since 2014, the digital native medium Rutas del Conflicto has sought to tell through the convergence of journalistic formats the stories of the Colombian armed conflict that have not been documented. The site, in addition to its more traditional investigations and features, has been characterized by developing a database construction methodology and mapping places in a journalistic way.

“What it does is that it builds a database that allows communication, a database for journalism,” said Parra, who added that this is a document that goes beyond being quantitative. “What we do is build a database that allows us to classify, and build maps, but that will also allow us to classify these records by other types of information.”

Their journalism investigations are accompanied by seven databases that unite all types of information and it allows them to affirm that the site has “the most complete and interactive journalism archive in the history of the war in Colombia,” with at least 1,500 records.

Those databases are a part of different projects that cover massacres, stories of those disappeared by the rivers, land disputes and including a map of survivors or family members of victims.

After the signing of the peace agreement, La Paz en el Terreno a project done in conjunction with Colombia 2020 came to fruition to cover the peace process by the newspaper El Espectador. It has two main objectives: to cover violence against social leaders and cover the reintegration of the former combatants of the Farc.

In the case of violence against social leaders, the site has already documented 220 murder cases. That database can be classified by certain information, for example if the leader was part of the LGBTI community, a union, if they fought for land restitution, if they were part of an Indigenous or Afro-descendant community, among other details. Because the number of murders "surpassed them," the team has managed to do more in-depth reporting on 130 of the 220.

Screenshot of La Paz en el Terreno project and its special report on the social leaders killed in the country after the signing of the peace agreement.

The Truth Commission also became interested in these investigations. Since the start of the Commission’s three-year term, which ends in 2021, Rutas has worked on some projects with them. Around April, however, other areas within the Commission that had never been in contact with the site began asking them for information.

According to Parra, they were interested in one of his investigations on companies and lands that gave an account of alleged agreements signed by the Public Force and the Prosecutor's Office with mining and energy companies in sensitive areas for land management. Usually these agreements took place in locations where social leaders protested the activity of these companies and would later end up in prison. “A terrible ethical dilemma […] these agreements showed that the companies were in the end financing the army, police and the prosecutor,” explained Parra.

"By May, every time a person [from the Commission asked us for documents] we would say, 'Listen, you ask for stuff by little chunks.' So they told us: 'Is there any chance you could give us all you have?” Parra said. "And we decided that yes, it was an honor that they had asked us to contribute during this moment and to the work of the Commission, which we feel is so important."

According to Parra, both the JEP and the Truth Commission received those 1,500 records. The journalistic investigations are listed with their urls, while download links were provided for the seven databases for which "they simply press a button and begin to download the data and then that information is reconstructed." Parra added that engineers from those entities upload the data to their respective servers and thus combine the information with what they already have.

Journalism to piece the truth and help in the healing process

"Journalism is an agent of memory and it deserves to continue being it in contexts of conflict and war, and Colombia is a very notorious case," Ginna Morelo, a Colombian journalist with 25 years of experience covering the armed conflict, told LJR. “This is because the tools of journalism strengthen and help present the different sides of the facts; from journalism, the participants of conflict can meet through the course made available; and from our work we propose the reconstruction of a political memory of violent events, their victims, perpetrators and contexts.”

Indeed, for Morelo, who is also the director of the masters in Scientific Journalism at the Pontificia Universidad Javeriana de Colombia, both the media and journalists have played an important role in narrating the conflict that "has resulted in more than a few contributions to investigations of historical and judicial purposes.”

For Morelo, handing over the documents to the JEP and the Commission is a recognition in some way of the work of journalists who have covered the conflict during the past 60 years.

"The contribution and the importance of journalism is so significant in the reconstruction of the memory of the conflict, that the work done responsibly and ethically contributes to clarifying [unknowns] from entities such as [the JEP and the Commission]," Morelo said. "I think it’s wonderful that it happens, because several of us have contributed in different ways at specific times and that shows that our work is useful, contributes to democracy and contributes to the clarification of the war."

In an interview with LJR, Ricardo Corredor, communications director of the Truth Commission, said he also agrees with this and believes that the Commission's work is done in a particular context precisely because “it comes to speak of a conflict about which much is known,” although, of course, not all.

“In the case of Colombia, we must recognize that it is not that the conflict we are experiencing went unnoticed. [...] One can have observations, criticisms of the way certain things were covered or that was covered more on one side than the other, with ideological tendencies, in short, one can make criticisms of course, but this is really a conflict that has been talked about, and that was covered by the media,” said Corredor.

The Commission has a specific time frame to try to explain from the historical point of view the 60-year armed conflict. At the end of the three years of its mandate, the Commission must deliver a final report with an explanation based especially on victim testimonies, but the perpetrators’ as well.

"All that work that journalism has done is a source that the Commission has and has been and will continue to use for this term to offer new understandings about our conflict," said Corredor.

According to him, in addition to the information from Rutas de Conflicto and La Paz en el Terreno, the Commission has received at least 500 reports from organizations of all kinds: human rights, civil society, the Armed Forces, international organizations, research centers and think tanks, among others.

“The important thing is to insist that all this is received by the Commission and that they become sources for the Commission's investigative work, and that reading all these reports, plus the reading of the thousands and thousands [of documents], I think there are already 9,000 testimonies, […] all this becomes material that the Commission works with,” explained Corredor.

Next year, the Commission must deliver its final report, which will be based on the sources that it has compiled, verified, corroborated and contrasted, Corredor said.

The information of Rutas de Conflicto has a similar use within the JEP. During the official delivery of the data on July 23, Judge Julieta Lemetre, on behalf of the JEP, explained that the information provided by Rutas de Conflicto is another source of material in its process of verifying information offered by those who voluntarily or obligatorily appear before the Jurisdiction to discuss their participation in the conflict.

“We verify these versions, we compare them with the collection of investigations that the State has had, especially the Prosecutor's Office, and there you realize by the same regulations they created of the insufficiency of this in contrast. So a third source of contrast is what civil society gives us and what the victims themselves, who are called to participate and who decide to participate as intervening parties in the cases, tell us," explained Judge Lemetre.

According to her, when these versions do not coincide, the JEP should do more tests and delve into the subject. "You can imagine then what they are giving us becomes another source of contrast that facilitates our work," she said.

Journalistic investigations also allow the JEP to build cases, she said. "Unlike ordinary justice where a fact is a case, at the JEP a fact is not a case, the cases are accumulations of facts, they look for patterns," she said. "So [this delivery of data] is one more input for the accumulation and pattern identification suggestions."

For Morelo, the impact of this delivery of data on Colombian journalism may go beyond this event, and she hopes that information will be requested from other media.

"I must say that in specific spaces things have already begun to take place that show that journalists have contributed as memory agents," Morelo said. “One of those issues is to make even a small contribution to that ethical conscience that our work requires; another is that more spaces for debate have been opened, meeting places in which today - faced with the challenge of a society always at war - we are still amazed by and formulate more and new questions that we need to address through research.”

These questions about how to improve, study and strengthen journalistic work arose, according to Morelo, due to the extreme coverage of the conflict. This is how, at the time, the journalists organization Medios para la Paz created the tool "To disarm the word: dictionary of Conflict and peace terms." The Colombian organization of investigative journalists Consejo de Redacción produced three guides to cover the conflict: "Clues to narrate peace," "Clues to narrate the memory," "Clues to cover the implementation of the peace agreement," of which Morelo is a co-author.

Additionally, there is UNESCO’s toolkit, "Communicating rights," and the Gabo Foundation’s book, "Peace with open eyes: journalism, communication and peacebuilding in Colombia."

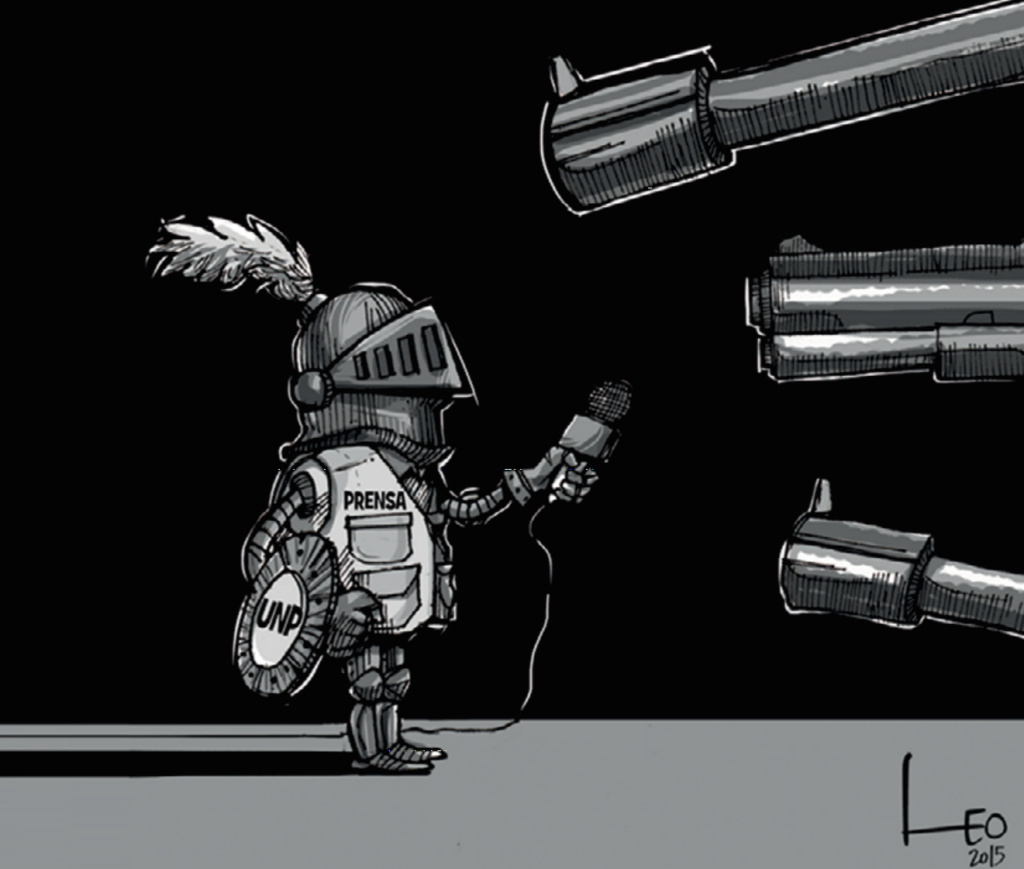

Ilustración de Leonardo Parra “Leo”. Tomada del informe 60 años de espionaje a periodistas en Colombia de la Fundación para la Libertad de Prensa. Colombia, 2014. (Cortesía FLIP)

Although the official delivery of data has already taken place, Parra assured that all the information that they continue to investigate and publish will also be shared. For Corredor, this is important since he believes that both journalism and the Commission share the same objective.

"I see a parallel in the spirit we both have, we are in the same -I will say in quotation marks- 'business,' which is the truth, the search for the truth," said Corredor. “But we understand that it isn’t that an absolute truth exists, [but rather] that the truth is a social construction, the truth is shared narratives, and shared narratives on which there is a consensus at the social level. Both journalism and the Commission somehow understand that their job of conducting a very rigorous investigation allows them to verify and, at the same time, then make a story that is credible, that gives an account, that moves and that manages to impact those who are receiving that story.”

Rutas del Conflicto hopes to continue with its work, which, according to Parra, has always moved in that line of contributing to the truth, “an inclusive truth, a truth that is not the truth of the State, that is not a truth that revictimizes , which also allows the delivery of information to judicial entities such as the JEP so that they can make their decisions, and also contribute to the Unit for the Disappeared."

These documents have been used by the Disappeared Unit, the Victims Unit, the Land Restitution Unit and even by victims when demanding their rights.

Precisely when a victim manages to recover their land thanks to a journalistic investigation by Rutas, it is an example for Parra of those small victories in the midst of that “frustrating” struggle shared by all journalists for wanting to change the world, despite knowing that this will not happen.

“If you don't get up thinking that this is going to change, then it will not. What happens is that it will never change, but it is up to you to wake up thinking that it will,” he said.

*LJR Interviewed Óscar Parra on two different occasions when they delivered information to the Truth Commission and the JEP respectively.

This story was originally written in Spanish and was translated by Perla Arellano Fraire.