For Percy Suárez, it is not easy to remember the day he traveled to eastern Bolivia to investigate illegal occupations and ended up staring down the barrel of a rifle.

Suárez was part of a small caravan of pickup trucks carrying five other journalists, several local workers and a few police officers. They were headed to a soy-producing area in the department of Santa Cruz to investigate reports of land seizures.

About 15 minutes after their arrival, a group of masked men emerged from the brush and began shooting, blowing out their trucks’ tires.

Suárez, then a videographer for the Red ATB television network, kept his camera on his shoulder as chaos broke out. He recorded the moment one of the men pointed his rifle directly at him and shouted for him to stop filming.

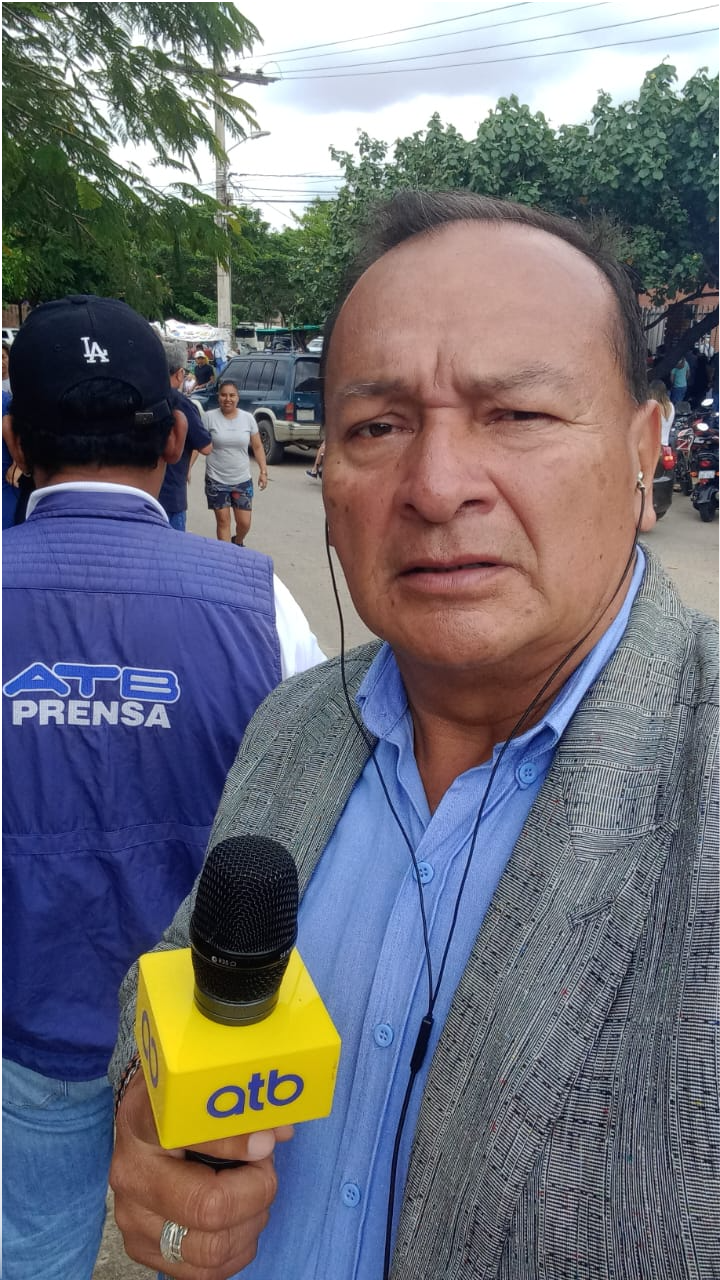

Bolivian journalists Percy Suárez. (Photo: Courtesy)

“It really is a wound that doesn’t heal,” Suárez told LatAm Journalism Review (LJR). “It’s obvious that talking about the case affects me, but I have to tell the story. Whenever it’s necessary, I have to tell my experience. If I stay silent, I think I’ll just get sicker.”

The attack on Oct. 28, 2021 — known as the Las Londras case, after the area where Suárez and his colleagues were reporting — is one of the most notorious examples of impunity in cases of violence against journalists in Bolivia. It is among the few attacks on journalists that have reached the trial stage, although four years later it remains stalled, said Raquel Guerrero, the journalists’ attorney, in an interview with LJR.

According to testimonies presented to authorities and the press, the armed men took Suárez and his colleagues to their camp. There, they forced the journalists and police officers to lie face down on the ground, kicked them and walked over them. Each reporter was interrogated separately, Suárez said.

The attackers ordered them to sign documents promising never to return and held them for six hours. The documents — later notarized by the attackers themselves — are now part of the court file.

According to Suárez, the Association of Oilseed and Wheat Producers (Anapo) had taken them to the site to document the situation. Suárez was with reporter Silvia Gómez López and cameraman Sergio Martínez Galarza from Red Unitel; reporter Mauricio Egüez Simoné and cameraman Nicolás García Iriarte from Red Uno; and journalist Jorge Gutiérrez Ávila from the newspaper El Deber.

The journalists later got their cameras back, damaged and riddled with bullet holes. Suárez’s network’s technical team managed to recover the footage, which helped pressure authorities to move the case forward. His video eventually appeared in the media and was shared with LJR.

“What gets me most is seeing my own footage that I recorded, and then seeing the injustice that, with such evidence, the case still doesn’t move forward,” Suárez said. “Instead of acting, they protect these people, these attackers.”

The five people who have been charged remain free. Guerrero explained she accused them of “attempted murder,” while the Public Prosecutor’s Office charged them with “attempted homicide.” For the attorney, what happened that day showed intent and premeditation. The maximum sentence for that crime is 20 years in prison. They also face other charges, including unlawful deprivation of liberty, torture, serious injuries, kidnapping, aggravated robbery, illegal possession of weapons and obstruction of press freedom.

The trial finally began this year on July 9. However, on Aug. 5, it was suspended after three of the defendants requested a change of jurisdiction — from ordinary justice to the Indigenous Native Peasant Jurisdiction (JIOC for its initials in Spanish). Guerrero argues the request was invalid because the defendants are not members of any Indigenous communities.

“We’re in a jurisdictional dispute. The Constitutional Court is the highest authority that must resolve this situation,” Guerrero said. “Meanwhile, the Las Londras case will remain stalled, paralyzed until that’s resolved and referred back to the Ordinary Court, where it was already being handled.”

As part of the International Day to End Impunity for Crimes Against Journalists, observed Nov. 2, the National Association of Journalists of Bolivia (ANPB for its initials in Spanish) and the Circle of Women Journalists of La Paz issued a statement demanding independent investigations and effective sanctions.

“We’ve conducted an assessment, and our conclusion is definitive: throughout this entire period — we’re talking about the government of the MAS [Movement for Socialism party] — we’ve lived under systemic violence with impunity,” ANPB President Zulema Alanes told LJR.

The trial for the attacks against the six Bolivia journalists began this year on July 9. (Photo: ANPB)

According to the ANPB, from 2021 to 2025 there were 679 violations of press freedom in Bolivia, none resulting in exemplary convictions.

“None of the complaints that journalists and our organizations have filed demanding investigations have achieved redress or justice,” Alanes said.

In Santa Cruz alone, there have been 15 complaints related to attacks on the press — in addition to the Las Londras case — but none have received a response, Alanes said. “There’s not even progress in the investigation.”

The Chapultepec Index, produced by the Inter American Press Association to monitor freedom of expression, ranked Bolivia as a country with severe restrictions on the press and one of the worst in the region when it comes to confronting impunity.

LJR requested information from the Bolivian Public Prosecutor’s Office about the Las Londras case and other crimes against journalists, but as of publication, no response had been received.

For now, victims and organizations such as the ANPB are pinning their hopes on the change in government with the arrival of Rodrigo Paz, which will end 20 years of MAS rule.

The ANPB has a meeting pending with the president-elect to present, among other things, the demands made recently ahead of the anniversary of the Las Londras case. Securing justice for crimes against journalists and creating a protection mechanism are among those demands.

“Where do I get my strength? That on Nov. 8 this government changes,” Suárez said. “There hasn’t been a single punishment for any of these aggressors — whether public officials, police officers or the so-called intercultural groups that claim to be a support arm of the government, which is where their protection comes from. We hope all this changes. That’s the hope we have.”

This article was translated with the assistance of AI and reviewed by Jorge Valencia.