The security crisis for journalists in Mexico is critical. 2022 is already considered the deadliest year for the press in that country since records have been kept, with 15 journalists killed as of August.

In a column for The Washington Post earlier this year, U.S. journalist Katherine Corcoran wrote about how Mexican journalists are torn between frustration and anger over the deaths of their colleagues and the understanding that journalists should never become the story.

Moreover, according to Corcoran, given the impunity that reigns in Mexico, not much can be expected from the authorities either.

If there is anyone who can do something to change the panorama of violence against the press, it is society itself. And Mexican journalists must urgently make society understand and value their work, so that it is society itself that demands safe conditions for the press.

"We have to do a better job of explaining to our audiences what we do and why [journalism] is different from other types of information. What a journalist does and what the standards are, the ethics, the way we manage to write our articles to be more transparent, but we must also explain to the public our role in maintaining freedom of expression," Corcoran said in interview with LatAm Journalism Review (LJR).

Katherine Corcoran was AP bureau chief for Mexico and Central America. (Photo: Courtesy of the Kellogg Institute, University of Notre Dame)

The U.S. journalist, who was for five years Bureau Chief, Mexico and Central America Associated Press, believes that in Mexico there is a historical distrust of society towards the press and that many people are unaware of the importance of journalism for the survival of democracy, unlike what happens in other countries.

"With so much information and with this confusion of sources, of fake news, of all of that, we've lost connection with our audiences, in the sense that they don't know us," Corcoran said. "I think almost the only thing that can help journalists on safety issues is the public’s support, the support of audiences. That they demand that we can do our jobs safely and without harassment."

The best way to win support from society, according to Corcoran, is as simple as telling stories that make people see the impact good journalism can have on their daily lives.

"If there is a trusted reporter or reporter who publishes correct stories and stories with impact, I believe trust in journalists and in journalism as a way to help and not harm people will grow," she said.

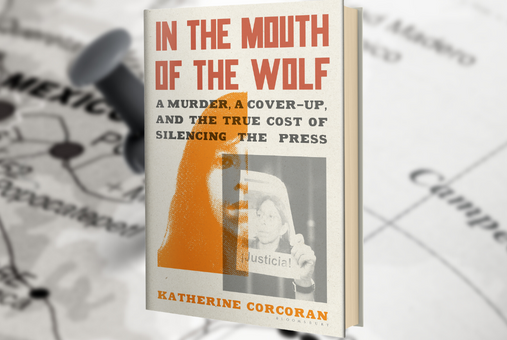

Corcoran wrote the book "In the Mouth of the Wolf: A Murder, A Coverup and the True Cost of Silencing the Press," which will be launched worldwide on Oct. 18. The book addresses the murder case of Mexican journalist Regina Martínez, which took place in 2012 in the state of Veracruz. Also, it’s about the impact that the disappearance of voices with a critical point of view can have on a society.

According to Corcroan, the Martínez case revealed the share of responsibility that journalism has had in the violence against communicators. The author said that, instead of investigating thoroughly, the media at the time took it upon themselves to spread the authorities' discourse. This discourse stigmatized the murdered journalists by describing them as corrupt and attributing their death to the fact that "they were on the wrong track."

"That was the government's script and it was very effective, because journalists also repeated it," she said. "Among international correspondents like me, there was a campaign by the federal government to tell us '[the murdered journalists] are not journalists like you, you have to understand that they don't have standards, they are corrupt, etcetera.' And there was no information to the contrary, there were no investigations."

However, Regina Martínez had a proven reputation for ethics and courage at the national level. The journalist, who was a correspondent for Proceso magazine in Veracruz, became known for stories revealing corruption and abuses by local and federal power elites. Her most emblematic works include her 2007 investigation into the rape and murder of a 72-year-old indigenous woman by members of the Mexican Army, as well as multiple reports on cases of corruption and violence during the administrations of governors Fidel Herrera and Javier Duarte.

"Regina's murder was the first time it became clear to us that it was a murder to silence a journalist, because everyone knew that Regina did not accept 'chayote' or bribes [...]. She also wrote very strong stories that other journalists did not want to touch," Corcoran said. "She had a national profile because she was a journalist with very strong ethics, fearless."

Despite not having met her personally and only having spoken to her a couple of times on the phone, Corcoran recalls that Martinez had been a contributor to the AP agency for some time, a position in which she displayed her professionalism.

"AP's standards are very high. So to collaborate with AP you have to be this kind of journalist, which at that time there weren't many in Mexico, much less in the states [outside the Mexican capital]," the author said. "I had no doubt of her journalism skills, of her standards, of her ethics, so for me it was obvious that [her murder] was an act to silence her."

The murder of Martínez had a great impact on the entire press in Veracruz, to the extent that many journalists fled and several news outlets chose to stop covering certain topics.

After Martínez's murder came other similar murders with equal national impact, such as that of journalist Miroslava Breach, in Chihuahua, and that of Javier Valdez, in Sinaloa, both in 2017. Corcoran thinks this scenario ended up affecting the way journalism was done during her time as chief of AP's Mexico bureau.

"These murders did change the ground for all journalists, no matter where they are from," she said. "This risk for journalists in Mexico obviously doesn't affect international correspondents as much, but it does affect the way we cover Mexico. Previously, Mexico was a very peaceful country to go out, to report... Now you have to plan, you have to have security protocols, etcetera."

Corcoran's purpose in writing "In the Mouth of the Wolf" is to bring the case of Regina Martinez and the violence against Mexican journalists to a wider audience. Also, as a way to add to the pressure that journalists and organizations are trying to exert to put a stop to the murders of journalists in Mexico.

"As a journalist from the United States, the least I could do is write about the problem for a larger audience, an audience outside of Mexico and potentially an international audience," she said. "Maybe something jumps, something comes out of exposing this story to a larger audience, so that something can be done, like an idea, a pressure. It's shaking the tree to see what falls."

For Corcoran, beyond the unacceptable and tragic nature of the violence against journalists, violence in a way is a manifestation of a strengthening of independent journalism in Mexico. The journalist believes there is a relationship between the attacks on members of the press and how their journalistic investigations brush up against organized crime and power elites’ interests.

"These murders are not because [journalists] were colluding [with drug traffickers] or were 'on the wrong track,' as they always say. Rather, it is because they are publishing things and brushing up against interests, revealing cases of corruption or abuse, or things that officials don't want anyone to see," she said. "For me, there must be a relationship between there being more journalists trained and willing to reveal, to expose what is happening locally in terms of corruption and that putting them at risk."

The book "In the Mouth of the Wolf", about the murder of Mexican journalist Regina Martinez, will be launched worldwide on October 18, 2022. (Photo: Courtesy)

During her time in AP's Mexico City office, Corcoran saw the birth of several independent news outlets that today publish high-impact corruption investigations, such as Animal Político, Mexicanos Contra la Corrupción y la Impunidad and Quinto Elemento Lab (where she co-coordinates the MasterLAB in Investigative Editing).

She also saw how the major print and electronic media began to open their own investigative journalism units.

For this reason, she is optimistic that independent journalism in Mexico will grow stronger to the point where it will function as a true watchdog and be a counterweight to the powers that be.

"In the history of journalism in Mexico, journalists who wanted to take on this watchdog role were the exception. Now, there are more and more of them, according to what I see," she said. "I know many of the reporters in the states [in the interior of Mexico] and they also have better standards, they are eager to investigate, they are doing things with more impact."

Despite this strengthening, journalistic stories revealing corruption scandals in Mexico rarely lead to resignations of officials or reparations for victims. In a country where 94.8 percent of crimes go unsolved, according to one report, public officials exposed by press reports rarely receive punishment.

"The more power, the fewer consequences," Corcoran said. "There is not a strong rule of law, it's very weak and that's why. Because there are no consequences, there is no change. I've talked a lot with journalists in Mexico about this issue, because they reveal it over and over, yet nothing happens."

However, she believes that Mexican journalists should not give into frustration or discouragement if their stories do not cause visible and immediate changes. It is enough, she says, for the public to be informed about cases of violence and corruption, because - just as in the case of journalists’ murders - only an informed society will bring about change and exert pressure on the justice systems.

"In the United States we say there is an official court, but there is also a 'court of public opinion,' and you can try someone in this court of public opinion. I think this is now more effective in Mexico. People need to know this information and someday the formal court of justice is going to change to lead to consequences for these types of activities," she said. "Even if there are no consequences for officials, it is worth it for the public to read, to know and to consume this type of information."

The trust in the press that Corcoran believes is necessary to exert pressure on the authorities must be strengthened with journalism that continues to expose the misuse of power, so that people are aware of what is happening.

"I have asked journalists in Mexico about this issue. Journalists believe in freedom of expression and information, and that the more information possible, the better," she said. "They say they keep putting out information because that is key to democracy. So, that’s their purpose in continuing to investigate and write, also hoping that someday things will change."