“We continue in the battle to inform. Venezuela needs information. Journalist, be brave but take care of yourself.”

Jesús Romero, a reporter from independent media outlet Código Urbe, gave this message from a hospital bed, wrapped in a blue sheet, with medical tape adhered to his chest. The Bolivarian National Guard fired buckshot that hit his stomach and a bullet that struck his leg, injuring an artery, while he reported on protests in Maracay, in the north-central state of Aragua.

Romero is one of at least 40 journalists reporting in regions outside of the capital of Caracas who’ve been attacked as of July 31, caught in a wave of protests and repression that swept the country after electoral authorities called a disputed election for President Nicolás Maduro. This is according to numbers from the Press and Society Institute of Venezuela (IPYS, for its acronym in Spanish).

The attacks – including baseless accusations of terrorism and “incitement to hatred” – have contributed to a climate of fear among journalists in the regions, where most work independently or for small media outlets, as in Romero’s case. It’s leading to self-censorship and the creation of information gaps in the midst of a post-election political and social crisis, according to representatives from journalist organizations in the country.

“We are seeing through data that Venezuelan journalists in Venezuela's regions and towns are more exposed to attacks and threats than in urban centers and state capitals,” Marianela Balbi, director of IPYS Venezuela, told LatAm Journalism Review (LJR).

In these places, far from the Venezuelan capital, journalists are easier targets for surveillance, since relationships between citizens are more direct and close, Balbi said.

Jesús Romero, reporter of the independent media outlet Código Urbe, was injured while covering protests in Maracay, Venezuela. (Photo: Screenshot of a video by the National College of Journalists, Aragua section)

“Journalists are less protected because the classic attackers – in many cases police officers, local authorities and even members of organized crime gangs – know where journalists live, who their relatives are and what their habits are, and that makes them more vulnerable than in urban areas where they are more anonymous,” Balbi added.

Making matters worse, since Chavismo came to power, more than 440 independent media outlets have closed in the country, which has left hundreds of journalists unprotected, said Carlos Correa, director of Venezuelan freedom expression organization Espacio Público.

“More than half of the country does not have independent media, there are no newspapers, radio and TV stations. Fewer journalists, less social fabric of solidarity with journalists,” Correa told LJR. “Many work in official media and there is less of a safety net. We have tried to strengthen protection, which is very important for community life.”

From Caracas, Maduro announced on Aug. 3 that the government had arrested 2,000 opponents during protests and would detain more. By contrast, on Aug. 4, Foro Penal reported 988 detentions since July 29.

Unfortunately, journalists are among those numbers, detained on charges ranging from terrorism to “incitement to hatred.”

Thirteen journalists from all areas of the country had been detained since July 28, as media outlet Runrunes reported on Aug. 5.

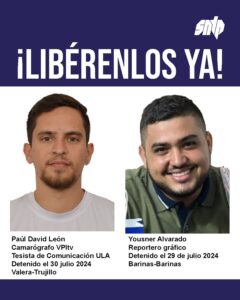

Paúl León, a cameraman for the Internet television channel VPItv in Valera, in the state of Trujillo in western Venezuela, is one of them. León was surprised by a group of police officers on motorcycles while he was preparing his camera to record a demonstration in his city on July 30.

According to a video that circulated on social networks, two police officers removed his work equipment, put him on a motorcycle and took him into custody. He did not resist. According to the National Union of Press Workers (SNTP), León remains at the state police headquarters.

Journalists from Trujillo, who preferred to remain anonymous, told LJR that they are being treated like criminals by state authorities. For this reason, they have decided to stay safe and stop covering the demonstrations.

That’s especially after the governor of Trujillo, Gerardo Marquéz, threatened the region's media in a radio program on Aug. 2 with “operation Tun Tun,” a term used to describe the raid of residences and the detention of members of the opposition by Venezuelan security forces.

The National Union of Press Workers (SNTP) published a poster demanding the release of Paúl León and Yourner Alvarado. (Photo: SNTP)

Meanwhile, in the western state of Barinas, photojournalist Yousner Alvarado, from media outlet Noticia Digital, was detained on July 29 and charged with terrorism, according to the SNTP.

The last case reported in the regions to date happened in Los Altos Mirandinos when reporter Deysi Peña was detained for taking and publishing photos on her social networks about a protest that occurred on July 30. Peña was at a gas station when she was approached by a regional police patrol on Aug. 2. She is accused of terrorism, incitement to hatred, resisting authority, vandalism and other crimes, and is still in detention, according to the organization Sin Mordaza.

Also on July 30, in the city of Cumaná, in eastern Venezuela, a criminal court issued an arrest warrant against independent photojournalist Pedro Rodríguez Carreño.

The order indicates as the alleged reason for arrest “the commission of the crime of promoting and inciting hatred,” provided for in article 20 of the Constitutional Law Against Hate and Peaceful Coexistence and Tolerance.

Journalists in Cumaná told LJR that the persecution against Rodríguez Carreño is due to his popularity and the publication of information related to the opposition protests on his social media accounts.

“Fear spread among many colleagues [within the state] after this complaint,” Nayrobis Rodríguez, IPYS correspondent in Cumaná and SNTP delegate, told LJR.

“Many tell me that they are in hiding, that they are afraid to publish, that they did not know whether to continue working in their media. They are in a state of anxiety and anguish," she added.

The U.S. Embassy in Venezuela called on detained journalists to be released immediately.

“We strongly condemn the continued use of ambiguous laws to harass, detain and arrest journalists for doing their work,” it wrote on social media platform X.

The type of attack that keeps the CNP and other press freedom organizations in Venezuela on alert is the discrediting and online stigmatization of journalists covering protests against election results, especially in the states of Aragua and Carabobo.

Organizations such as the CNP and the SNTP reported that since July 31, images with the faces of more than a dozen journalists with the label “terrorist wanted” have circulated on social networks.

Another similar image shows the photographs of three women journalists with the label “Operator of the fascist right in Aragua,” among them the former secretary general of the Aragua section of CNP, Amira Mucic, and the current secretary of the Carabobo section of CNP, Ruth Lara Castillo.

The CNP condemned the attack and urged authorities to punish those responsible.

There is an online campaign to discredit and stigmatize journalists covering the protests against the election results. (Photo: Colegio Nacional de Periodistas, Aragua section)

“It is a campaign of intimidation so that the media and journalists basically stop reporting what is happening,” Eilyn Torres, secretary general of the Aragua section of the CNP, told LJR.

"These journalists who have been identified there have been providing journalistic coverage of the protests, which is what in fact they want to silence, to make it appear to the world that these protests are not taking place,” she added.

Torres said that it is no coincidence that, at least the Aragua journalists affected, are well-known figures in the state for their careers and credibility, and are close to organizations such as the CNP.

“They are very reliable sources of journalism, you trust what appears in their profiles and in their personal accounts, which are linked to really reliable information,” she said. “Of course, those are the first poles that some sectors believe it is appropriate to tear down.”

For her part, Lara said that the campaign had created fear among journalists in Carabobo, especially among younger journalists who have little experience covering conflicts. This, she said, has caused some communicators to delete posts about the events from their social networks and even make their accounts private.

“When there are kids who are so new, there is also a lot of fear, and it is no wonder,” Lara said. “When you see a photo of you rolling around in groups on the Internet, in which they call you a ‘terrorist financed to generate chaos in the State,’ of course it made some even take down the publications they had already posted about the protests.”

According to Lara, the violence that the press has faced in recent days has also had an effect on access to reliable sources. Not only are people afraid to talk to the press, she said, but journalists themselves fear that interviewing citizens or protesters could make them a target for authorities.

“When you go to interview someone now you are also afraid that that person will also be persecuted for anything they say, because in fact we do not know what the authorities think inciting hatred means. For them, anything is inciting hatred,” Lara said. “That puts us in a complex situation to be able to report.”

*André Duchiade collaborated in the reporting of this article.