Faced with an increase in violence against the press in Latin America, two South American journalists are promoting a Model Law for the protection of journalists that could be applied worldwide. Chile is the country that has made the most progress in this regard. Paraguay, Mexico and Brazil follow.

In view of the advance of organized crime over Paraguayan institutions and the almost total impunity in the cases of murdered journalists, freedom of expression organizations in that country will present in April a bill that contemplates the creation of individual, collective and psychosocial protection mechanisms for members of the press.

Authors of the investigation "Ejército Espía [Spy Army]" do not rule out going to international mechanisms to bring justice to victims of the Pegasus spyware in Mexico, after revealing that the spying on journalists and activists in that country comes from a secret military intelligence center and that the Secretary of Defense had knowledge of it.

More than 200 threats and two murders of journalists were recorded by Colombia's Foundation for Press Freedom (FLIP, by its Spanish acronym) during 2022. As part of Colombia's Journalist's Day, commemorated on Feb. 9, FLIP published its annual report. It found that there was scant progress for a press attacked by armed groups and public officials.

For experts, as long as there is no comprehensive policy focused on prevention, protection and prosecution of crimes against journalists, it will be difficult for the panorama to change. But the support of society is also needed: It needs to understand and defend freedom of the press as a collective right.

The Brazilian government announced the creation of the National Observatory of Violence against Journalists, a demand from organizations defending press freedom and journalists. National Secretary of Justice, Augusto de Arruda Botelho, told LatAm Journalism Review (LJR) that the creation of the new body was motivated by the "escalating violence" against journalists in the country.

A little more than a month after the departure of President Pedro Castillo, the Peruvian press has experienced more than 70 cases of aggressions including beatings, insults and vandalism of equipment and facilities by demonstrators, as well as threats, obstruction of coverage and even an attack with rubber bullets by police officers.

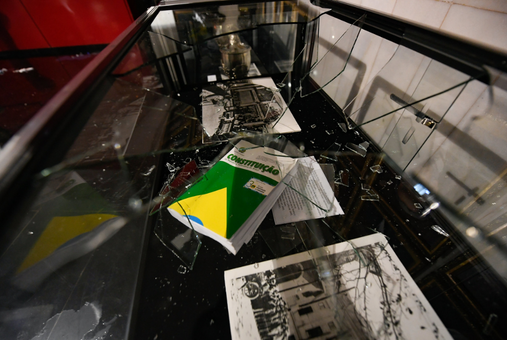

At least 12 journalists were physically assaulted, robbed or threatened with death by groups of Bolsonarists while covering the terrorist acts perpetrated by supporters of former Brazilian president Jair Bolsonaro on Jan. 8 in Brasilia. Thousands of them stormed and vandalized the National Congress, the Planalto Palace and the Supreme Court in the face of inaction by police officers present, who in more than one case also refused to help journalists.

At least half a dozen journalists were victims of theft, intimidation and obstacles to carry out their work by members of organized crime during the wave of violence unleashed on Jan. 5 in the capital of the state of Sinaloa following the arrest of Ovidio Guzmán, son of "El Chapo."

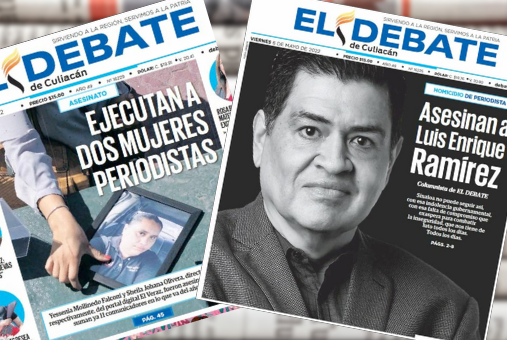

Twenty-nine journalists and communicators were murdered in Latin America and the Caribbean in 2022, according to data from the Committee to Protect Journalists (CPJ) counted up to Dec. 21. This represents a 163 percent increase over 2021. Mexico and Haiti lead the ranking of murders of press professionals.

Fifteen journalists from digital outlet El Faro of El Salvador have filed a lawsuit in a U.S. court against NSO Group, the Israeli company that makes the Pegasus spyware. “It is necessary to set a precedent so that the companies that promote this espionage market, as well as the customers that run this program, know that their actions have consequences,” said Julia Gavarrete, one of the journalists from El Faro who filed the lawsuit in U.S. courts.

With the murder of Pedro Pablo Kumul on Nov. 21 in Veracruz, at least 17 members of the press have been murdered in Mexico in 2022. Journalists and organizations demand justice and agree that only the correct administration of justice can stop the bloody wave that threatens journalism in that country.