To mark the end of 2020, the LatAm Journalism Review (LJR) team put together a list of the most interesting and important stories we’ve covered this year. Inevitably, many deal with the global COVID-19 pandemic and its impact on the industry -- which led to layoffs and restrictions on information and access to sources, but also innovation in how we report stories and how professors prepare the next generation of journalists.

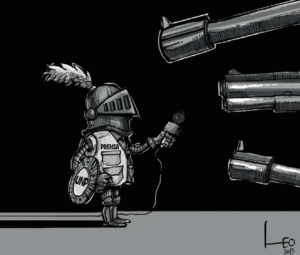

To continue our role as a watchdog on violence against journalists in the region, we also brought you articles about lawsuits, threats and violence being used as tools to silence investigative reporting. We also shared accounts of journalists who were fighting against those attempts in order to keep their communities informed.

We’ve also focused on innovation and keeping up with changes to the profession. The LJR team shared how colleagues are navigating the freelance world, and how others are taking advantage of scholarships or fellowships abroad. We told you about research on working conditions and ethical debates surrounding how we cover the news.

Finally, 2020 was a big year for us as we launched a new digital magazine, and we want to thank you for following us as we work to bring you original, in-depth reporting on journalism and press freedom in Latin America and the Caribbean. We hope to see you again in 2021.

At the start of the coronavirus pandemic, much was unknown about how long the disease would stick around. In response, media outlets made big changes, like opening access to their daily coverage on COVID-19 open to the public and creating fact-checking projects to debunk fake news. But journalists were also laid off and others relegated to reporting from home or venturing to the street with minimal protective equipment.

The global pandemic took universities by surprise, and journalism professors across the region were called to adapt to it. With the suspension of in-person classes, many journalism professors migrated their courses to online platforms since there was no short-term prospect of returning to the classrooms. Among the many challenges faced by journalism schools is knowing how to deal with the differences in students’ access to technology, unstable internet and lack of available equipment.

Freelancers in Latin America: How to put a price and charge for your work

There is a recurring myth that says journalists aren’t good with numbers because if they were, they wouldn’t be journalists. However, not knowing how to count is a luxury freelance journalists cannot afford. This is because the lack of a fixed revenue stream requires more organization, either to deal with periods of less work or to deal with recurring delays in payments for work done. Across the continent, journalists who dedicate themselves exclusively to working as freelancers shared the common problems they face and the methods of survival they developed in a competitive and undervalued market.

Two journalists under state protection were murdered in Mexico in 2020. They were beneficiaries of the Mechanism for the Protection of Human Rights Defenders and Journalists, linked to the Mexican government. After the deaths, NGOs asked for the reinforcement and review of protective measures. The LatAm Journalism Review spoke with representatives of these organizations to find out what the deaths reveal about the effectiveness and performance of the Mechanism, which was created in 2012.

Searching for the truth about the Colombian armed conflict, journalism receives recognition

When the journalism site Rutas del Conflicto and the project La Paz en el Terreno handed their investigations and database over to the Commission for the Clarification of Truth, Coexistence and Non-Repetition, it undoubtedly turned into a historic act for the journalism in that country and as a way of recognizing its work. A month later, according to Óscar Parra, director of Rutas del Conflicto, the outlet would be the first to officially give information to the Special Jurisdiction for Peace (JEP).

The staff at La Costeñísima radio in Bluefields, Nicaragua, made up of ten young journalists, are struggling to do their jobs in the face of power cuts, harassment, police intimidation and death threats. For doing critical journalism, with allegations of corruption and human rights violations in the country, La Costeñísima has suffered attacks on several fronts. The station is an example of how the independent press tries to survive in the country in the face of persecution by President Daniel Ortega's authoritarian regime.

How do journalists' working conditions impact the quality of information that reaches the public? This is what Brazilian researcher and journalist Janara Nicoletti wants to answer with the model developed in her study “Impacts of the precariousness of the work of journalists on the quality of information.” “The precarious working conditions and the [poor] performance of the team is something that every journalist already feels, knows that it happens. But, in a way, it is something like the norm of the profession: you will find a way to get by, you will find a way to cope, to make the story,” Nicoletti said.

Peruvian journalist faces new defamation lawsuit and denounces smear campaign against her

Peruvian journalist Paola Ugaz faces a new lawsuit for aggravated defamation, this time from the director of the Peruvian news site La Abeja. It’s the most recent incident of legal trouble for the journalist related to her investigative reporting – published in books, news articles and in documentary appearances – about the Sodalitium Christianae Vitae, a lay community linked to the Catholic Church in Peru.

Culturas em Conflito: imagem desclassificada do Prêmio Vladimir Herzog. Foto: Joedson Alves

In an atypical decision, the jury for the Vladimir Herzog Award for Journalism and Human Rights excluded the work “Cultures in Conflict” from the finalists in the photojournalism category. The reason: a formal complaint from the Hutukara Yanomami Association (HAY), which claimed that the photograph violates the image rights of the Indigenous people portrayed. "Disqualification put me in a position of violating human rights, to which I refuse to be assigned. I was the eyes of society on the government’s violation against Indigenous peoples,” the photojournalist said.

We see them in Twitter and LinkedIn profiles pasted next to –or sometimes even preceding– current job titles. They’re badges of pride. Nieman ‘68, Knight-Wallace ‘19, JSK ‘84. For decades, dozens of journalists from Latin America and around the world have taken advantage of fellowship programs at prestigious U.S. universities that offer the opportunity to pursue special reporting projects, expand knowledge and skills in a particular area of study or just grow intellectually during a sabbatical year to become a better journalist.