After a bloody start to 2022 for the press in Mexico, with a total of four murders and two failed murder attempts of journalists during January, cases of violence against members of the press continued during the second month of the year. Meanwhile, Mexico’s president, Andrés Manuel López Obrador, has raised the tone of his hostile discourse towards the country's media.

The Mexican press was still dismayed by the murders in Tijuana of photojournalist Margarito Martínez and journalist Lourdes Maldonado, on Jan. 17 and 23, respectively; and for the stabbing death in Veracruz of journalist José Luis Gamboa on Jan. 10, when Roberto Toledo, a cameraman and video editor for the Monitor Michoacán news outlet, was shot to death on Jan. 31 in the city of Zitácuaro, state of Michoacán.

The journalist was shot eight times by an unknown number of people after hearing the bell and going out to open the door of the office of one of the news outlet’s editors, where he had gone to record a video column. Toledo died before emergency services arrived at the scene, reported El País.

“Exposing corruption by corrupt governments, corrupt officials and politicians led today to the death of one of our colleagues,” said Armando Linares, director of Monitor Michoacán, in a Facebook broadcast shortly afterwards. Linares also said that his outlet had received death threats as a result of its criticism of municipal and state authorities.

Armando Linares, director of Monitor Michoacán, announced the murder of his colleague Roberto Toledo during a Facebook livestream. (Credit: Facebook livestream screenshot)

The Lopez Obrador administration condemned Toledo's murder, but at the same time tried to divert attention from the victim's profession, which organizations such as the Committee to Protect Journalists (CPJ) considered an attempt to minimize the seriousness of said attack on the press.

Jesús Ramírez Cuevas, spokesman for the López Obrador administration, said in a tweet that Toledo was not a journalist, but rather a collaborator in a law firm, despite the fact that in a previous tweet, he had referred to him as a journalist. This stance was mimicked by local authorities in Zitácuaro. However, Linares later clarified that Toledo, in effect, had created content for Monitor Michoacán and that, although he was also an assistant to lawyer Joel Vera, the latter is a columnist for the portal and shares offices with the digital media outlet.

“We condemn the cowardly attack that took place in our facilities, clarifying that the offices of Monitor Michoacán are also located in that same location. We ask the Zitácuaro Town Council, as well as other media, not to attempt to misrepresent the information, by spreading that [Toledo] was not a collaborator of a digital news outlet,” Vera wrote on his Facebook account.

A day after Toledo's murder, on Feb. 1, two photojournalists were attacked in Mexico City while reporting. Ernesto Álvarez, from Channel 11; and Iván Montaño from Diario Pásala, had gone to capture images of two killings in the Azcapotzalco district when they were beaten up by local residents. Another reporter present at the site, Juan Carlos Alarcón, reported that Mexico City police were the ones who provoked people to attack the journalists.

Two young men were arrested for the attacks and local authorities said they would launch an investigation. One of the journalists suffered a dislocated nose, while the other sustained a head injury, according to local media.

Hours later the same day, in the state of Quintana Roo, an armed man broke into the house of journalist Netzahualcóyotl Cordero, director of the local digital news outlet CGNoticias. The journalist said that his attacker first threatened his female cousin with a firearm before entering his home with the intention of shooting him.

“He literally told me 'journalist, I came for you.' He put a gun to my head and when he reloaded the gun, I pulled his hand up with my left hand. Many neighbors came out and took away his weapon and they hit him with that very weapon, they beat him," Cordero told the Marcrix Noticias news outlet.

The attacker was taken to the hospital for his injuries and three days later he was discharged and put under preventive detention. The journalist confirmed that he had previously received threats by telephone, as well as images of the front of his house, which lies between Cancun and the municipality of Isla Mujeres.

The most recent incident of violence related to the press happened on Feb. 6, when Marco Ernesto Islas, son of journalist Marco Antonio Islas, was shot to death in Tijuana. The Baja California State Prosecutor's Office said in a statement that the victim was not a journalist and that his family had said that he did not carry out any news work.

However, the media reported that Islas was the founder of the news outlet NotiredesMX, which closed in 2019. As recently as Jan. 31, Islas’ father had posted an op-ed on his Facebook news page Zona Norte Noticias in which questioned the level of responsibility of former Governor Jaime Bonilla in the death of journalist Lourdes Maldonado.

“For now, we are not considering this case [as an attack on a journalist], since there are no indications that he was working at the time he was attacked. In addition, we have no evidence at this time that the attack happened as a direct result of his work. However, we will continue to monitor the case very closely,” Jan-Albert Hootsen, representative in Mexico of the Committee to Protect Journalists (CPJ), told LatAm Journalism Review (LJR).

Words that stigmatize from Mexico’s National Palace

During the first days of February, president López Obrador has spent more time and added more labels to his verbal attacks spoken during his habitual morning press conferences. He has even made direct accusations against specific journalists.

López Obrador called journalist Carlos Loret de Mola "corrupt", "mercenary" and "beater" after an investigation into the president's son. (Credit: Latinus broadcast screenshot)

"I think we see the most dangerous consequences of President López Obrador's constant anti-press rhetoric in how public opinion in Mexico feels the urgency to address violence against the press," Hootsen said. "If we consider that the president continues to enjoy fairly wide support in Mexico and that the opinion of many people who support him is influenced by his rhetoric, it turns out they share the president's hostility towards the press."

After the publication of the investigation "This is how AMLO's Eldest Son Lives in Houston," by the organization Mexicans Against Corruption and Impunity (MCCI, by its Spanish acronym) and the digital platform Latinus, on Jan. 27, the president criticized several times in the following days journalist Carlos Loret de Mola, presenter of Latinus, and described him as a "beater, corrupt, a mercenary, without ideals and without principles."

Since the beginning of the López Obrador administration, in 2018, Loret de Mola has broadcast several investigations on alleged cases of corruption involving direct relatives of the president on his show. This latest exposé revealed that the eldest son of the president lived in a luxurious house in Houston that allegedly belongs to a PEMEX contractor.

Another journalist who was singled out by the president was Carmen Aristegui, who rebroadcast the MCCI and Latinus exposé on her show “Aristegui en Vivo.” The journalist drew parallels between the scandal of the house of López Obrador's son with that of the so-called "White House" of then wife of former President Enrique Peña Nieto.

In response, Lopez Obrador said on Feb. 4 that Aristegui was a supporter of the "conservative" bloc that is against his administration and called the reports she presents on her show "slanderous."

"[...] Carmen Aristegui holds, with subtlety, to the maxim of the 'journalism underworld,' that says that slander, when it does not stain, tarnishes," said the president.

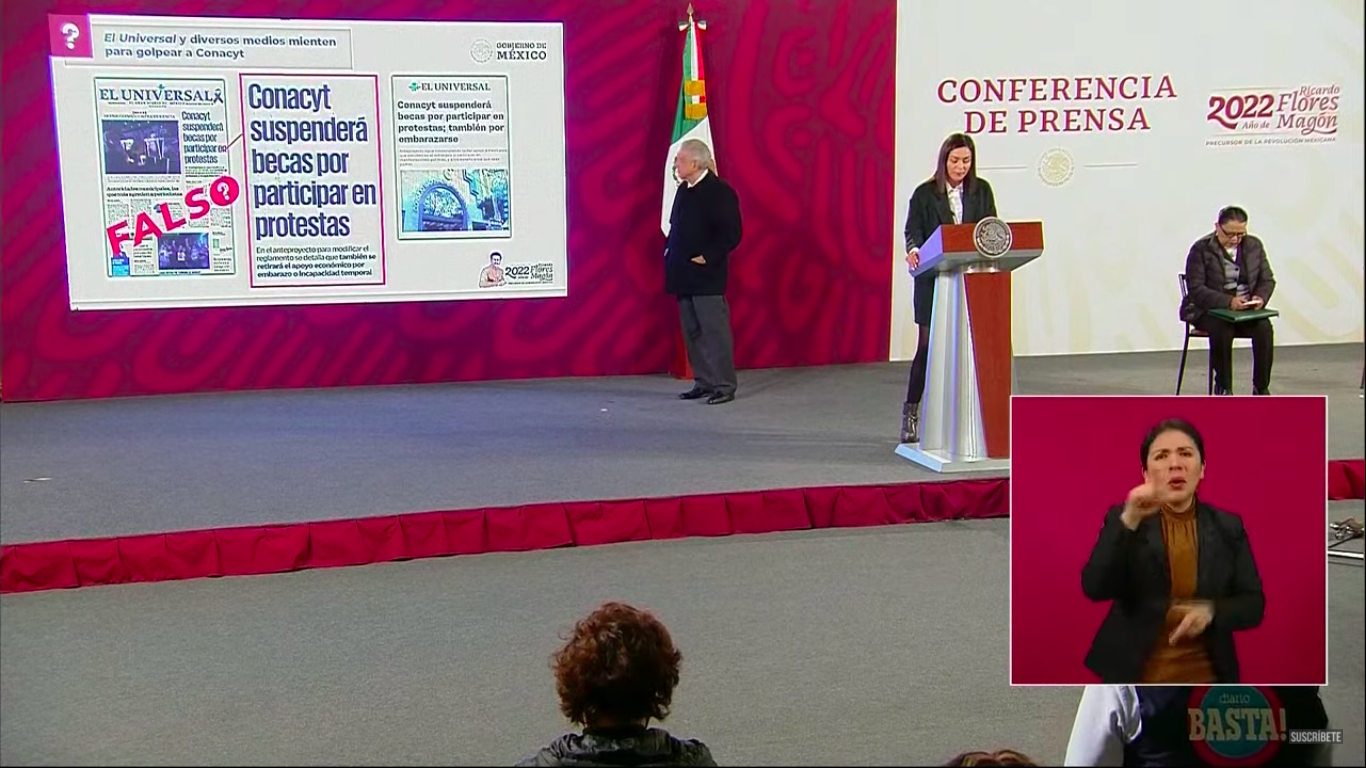

Since before being elected president, López Obrador has used the term “conservatives” to discredit anyone who opposes his policies. Since 2020, the president has included a section during his morning conferences called "Who's who in fake news?” during which he retorts and disqualifies criticism from the media and journalists.

López Obrador dedicates a section in his morning conference to refuting and disqualifying press reports. (Credit: YouTube streaming screenshot)

Other expressions López Obrador constantly uses to refer to the press include “puppets,” “hypocrites,” “double face,” “‘fifi’ press,” “neoliberals,” and “power mafia.”

“[The attitude against the press] not only diverts attention from the few public policies that the López Obrador government has developed to combat impunity and improve the protection of journalists in Mexico, but also generates open hostility towards journalists who have been threatened because of their work,” Hootsen said. “The best example is the case of journalist Azucena Uresti, who was threatened last year, allegedly from the leader of the Jalisco New Generation Cartel. Although the president said that these threats were unacceptable and that the case had to be dealt with immediately, I saw many expressions of hatred towards Uresti on social media, even people who said that she 'deserved it' for 'being against the president'”.

On Feb. 4, the Inter-American Press Association (IAPA) announced that it had sent a letter to López Obrador to urge him to stop his “stigmatizing speech against the press,” since, it stated, he could be giving crime “carte blanche” to silence journalists.

“We ask you to face the gravity of the hour with all the necessary energy and decision and, in this framework, to suspend all stigmatizing speech against the media and reporters. Because this practice [...] is an incentive for the violent to unleash their murderous fury on defenseless journalists,” stated IAPA in its letter. “When the press is disqualified, attacked, and confronted as a political strategy, it leaves the door open to the violent and the intolerant.”