Mexican journalist Anabel Hernández has spent much of her nearly three-decade career investigating and denouncing corruption and complicity between organized crime and Mexico’s government.

Her investigations also address issues such as drug trafficking, sexual exploitation and labor abuse. Her work has earned her awards such as the Golden Pen of Freedom, from the World Association of Newspapers and News Publishers (WAN-IFRA); the National Journalism Award of Mexico; the Freedom of Speech Award, from Deutsche Welle; and the International Journalism Award, from the newspaper El Mundo.

Since 2013, Hernández has been under the federal government's Protection Mechanism for Human Rights Defenders and Journalists, as were some of the journalists who have been murdered in Mexico in 2022 so far. Hernández herself has been a target of death threats, armed attacks, and theft of her work material on multiple occasions.

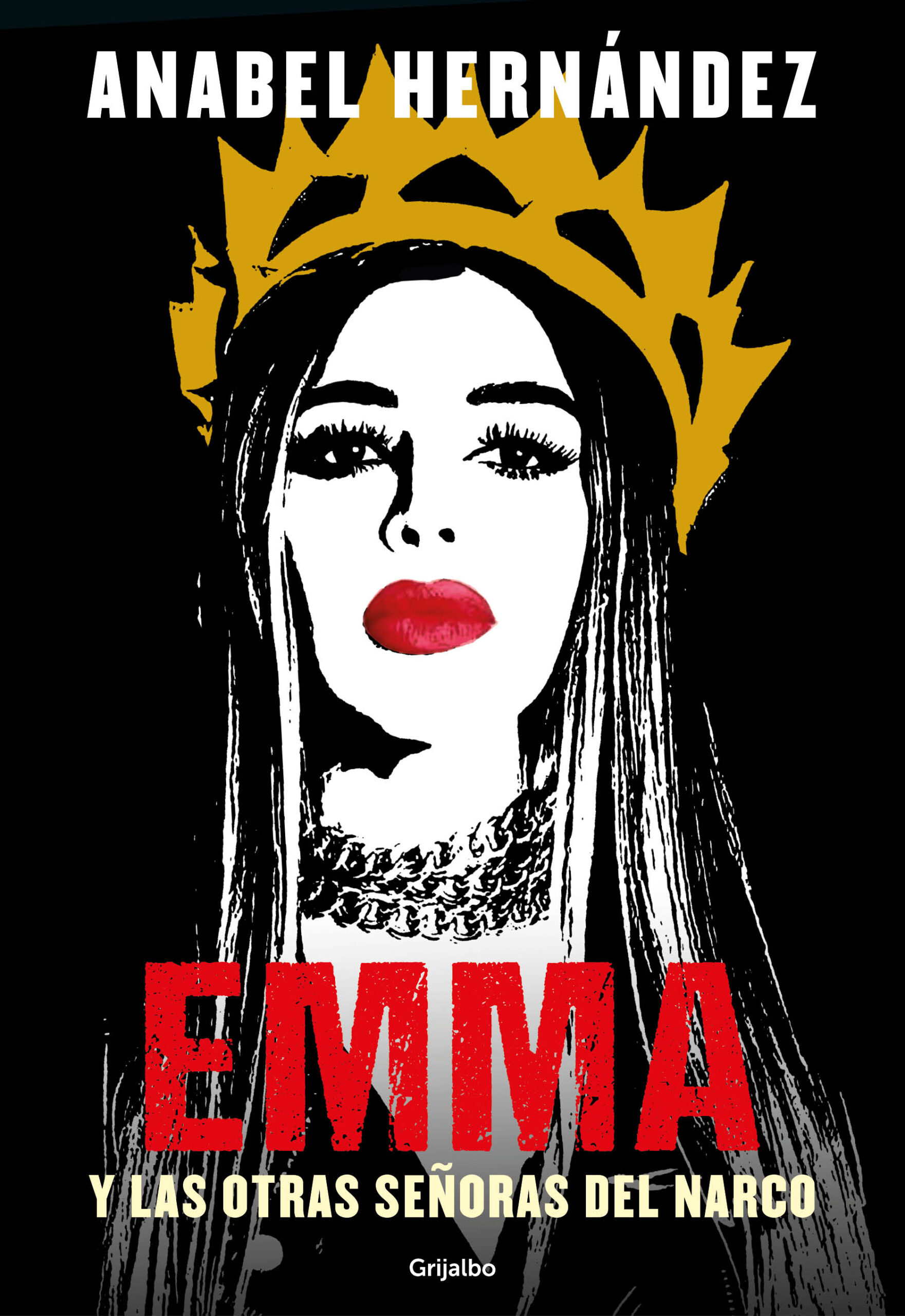

Author of books such as "Emma y las otras señoras del narco" [Emma and the other narco ladies] and “La verdadera noche de Iguala: La historia que el gobierno trató de ocultar” [The true account of the night in Iguala: The story the government tried to hide] believes the Mexican protection mechanism will not work as long as crimes and attacks against journalists are not investigated and adequately punished.

But, most of all, Hernández believes the current wave of violence against the press will not subside as long as President Andrés Manuel López Obrador continues to spread a hostile discourse against it that paints journalists as the enemy.

In Mexico, investigative journalism like the one carried out by Hernández is inconvenient for politicians, businessmen and criminal organizations, while at the same time it’s fundamental to society. Hernández believes journalists must train and protect each other, and experienced journalists must mentor new generations of journalists on how to keep an eye on those in power.

It should not be a heroic act taking unnecessary risks, Hernández said. Rather, it should be about defending people’s human right to be well informed.

Below is an interview Anabel Hernández granted LatAm Journalism Review (LJR), as part of our "Five Questions" series.

(Her answers have been edited for clarity and brevity.)

1. In your recent book "Emma y las otras señoras del narco” [Emma and the other ladies of the narco] and in your previous publications you talk about figures from organized crime and politics. Both arenas are precisely those singled out as responsible for the violence against journalists in Mexico. How do you handle that risk?

I am a 50-year-old journalist with 29 years of experience. Over the years, I’ve been able to develop a research method and an intuition that allows me to do my work with great caution. It is similar, I think, to the experience that a soldier acquires after years in different wars: he learns to distinguish the terrain, he learns to identify when he is about to cross a minefield, he learns to read the signs and to walk on it. Unfortunately the work is very risky and there is always the possibility of stepping on a mine and being thrown into the air.

Unfortunately, that’s what practicing journalism in Mexico is like, as well as in other parts of the world. Mexico is a country that lives in a war between drug cartels, where part of the institutions and public officials are in collusion with one side or another. If we journalists cannot even trust the authorities, who can protect us? Many of us have learned through bitter experience to protect ourselves.

I work alone because of the risk level of my work. The armed attacks I have suffered have forced me to isolate myself so as not to affect colleagues. And, on the other hand, there is censorship and big interests in Mexico’s media, so it’s hard to find places to publish. But I think the best way to reduce the risks of walking on the minefield is to work with a solid team, be it honest news outlets, academic journalistic research centers or journalists' collectives.

2. Several of the journalists who have been killed and threatened in Mexico were under the protection mechanism of the Ministry of the Interior. Do you think this mechanism is outdated or why has it not given good results?

I myself have been under this mechanism since 2013 and, even so, I have suffered armed attacks and break-ins at my home to steal my files. I think the mechanism as such is a good idea, it’s necessary, but it cannot work because as long as the authorities responsible for dispensing justice do not investigate with true autonomy and interest the attacks, intimidation or murders of journalists, these will continue.

For me, there are currently four main factors why attacks against freedom of expression continue to increase:

3. So far in 2022, seven journalists have been murdered in Mexico and many others have escaped murder attempts. What would you say are the causes of this dramatic increase in violence against the press in the country in such a short time?

The book "Emma y las Otras Señoras del Narco" has unleashed threats and attacks against the Mexican journalist. (Photo: courtesy)

In my view, it’s due to the four factors mentioned above. In addition, there is a wave of terrible misinformation circulating on YouTube channels and social networks, and clear hate campaigns against journalists. It is very serious when a president spends more time attacking journalists and the media than talking about structural problems in Mexico. When a government considers journalists more dangerous than drug traffickers or inept officials, we are talking about an inverted world that forces us to question "why?" The search for that answer is an urgent journalistic task.

4. Why would you say the risk you have faced in recent years, after the publication of your research, has been worth it?

I am a passionate human being. I believe deeply in my work as a journalist as a way of not remaining indifferent or passive in the face of acts of abuse of authority, human rights violations, violence, and crime that occur in my environment. I think every human being should find a way not to become cynical. Journalism is mine, to see the horror and to see the beauty.

I believe accurate and timely information contributes to creating a more equitable, fairer society, more aware of individual and collective responsibility for what happens around us. I believe that information positively empowers citizens and I believe there are increasingly more varied interests in the world that would like to see weak, uninformed citizens, not empowered citizens.

But my passion for the search of truth is neither irrational nor naive. I constantly question if it's worth it, if I should continue. Many times I have doubts. But in the end I always answer yes, it's worth it. "Indifference is the dead weight of history," wrote the Italian journalist and philosopher Antonio Gramsci. The style of journalism that I do is my way of not being indifferent and not being a dead weight in this world.

5. What advice do you give to journalists in Latin America who are hesitating to continue their investigations into corruption for fear of putting their lives at risk?

I don't believe in elite journalism, I don't believe in indifferent journalism, but I don't believe in partisan journalism either. I don't believe in kamikaze journalism, I don't believe in “heroic” journalism. The world needs more honest, committed, vibrant, and humane journalists. The activity carried out by a journalist is irreplaceable, we are the historians of the present.

I don't think that all journalism that is serious and worth doing should always be dangerous. There is a lot of fundamental journalism that does not always fall into a situation of risk. I think that's where we all should start on that path. We cannot and should not walk through a minefield without experience. No general can send an amateur soldier to identify mines in a war field, no amateur soldier should agree to go or volunteer.

In the environment that exists in Mexico and many other Latin American countries, experience is a must. It is necessary to train new generations of journalists. In newsrooms, in groups of journalists. There should be greater interaction among experienced journalists trained in good journalism practices, and new generations of journalists. New generations must be entrusted with research that gradually grows in complexity. They must be included in the ethical and philosophical debates of journalism, in the debates on editorial decisions, on topics to be investigated.

Journalists must empower our voices in newsrooms. We are the main defenders of the human right of people to be truthfully informed. We are the custodians of that right. Our main objective must be to survive in order to continue doing so.