In March 2025, a macabre discovery shocked Mexico. On a property known as Rancho Izaguirre, in the state of Jalisco, authorities found what appeared to be a cartel’s extermination and forced recruitment center, where they discovered human remains, clandestine crematoriums and signs of hitman training activities.

Investigations by the authorities found many of the victims had been lured there by false job offers on social media.

For some disinformation experts, this case revealed the rapid evolution of online scams, which have stopped being simple frauds meant to steal money or data and have turned into a gateway to crimes with tragic consequences.

Así usa TikTok el CJNG para reclutar jóvenes | Noticias de México | El Imparcial https://t.co/BLZfn6MUcb pic.twitter.com/bY0q02hve9

— EL IMPARCIAL (@elimparcialcom) March 26, 2025

“Before, they were just financial scams that stole your banking information. But now we’re seeing, in addition to these scams, theft of personal information, theft of intimate content that is later monetized through platforms like Telegram,” Paul Aguilar of SocialTIC, the Mexican organization focused on training and research on digital technology and data, told LatAm Journalism Review (LJR). “We’re also seeing it used a lot for organized crime recruitment.”

As digital scams have become increasingly common, sophisticated and dangerous, media outlets across the continent are developing tools to help consumers not only identify disinformation but also avoid being scammed. LJR spoke with experts from Agência Lupa in Brazil, Factchequeado in the United States and SocialTIC in Mexico, who explained ways journalists can train themselves, investigate and develop educational materials to help audiences identify these types of content.

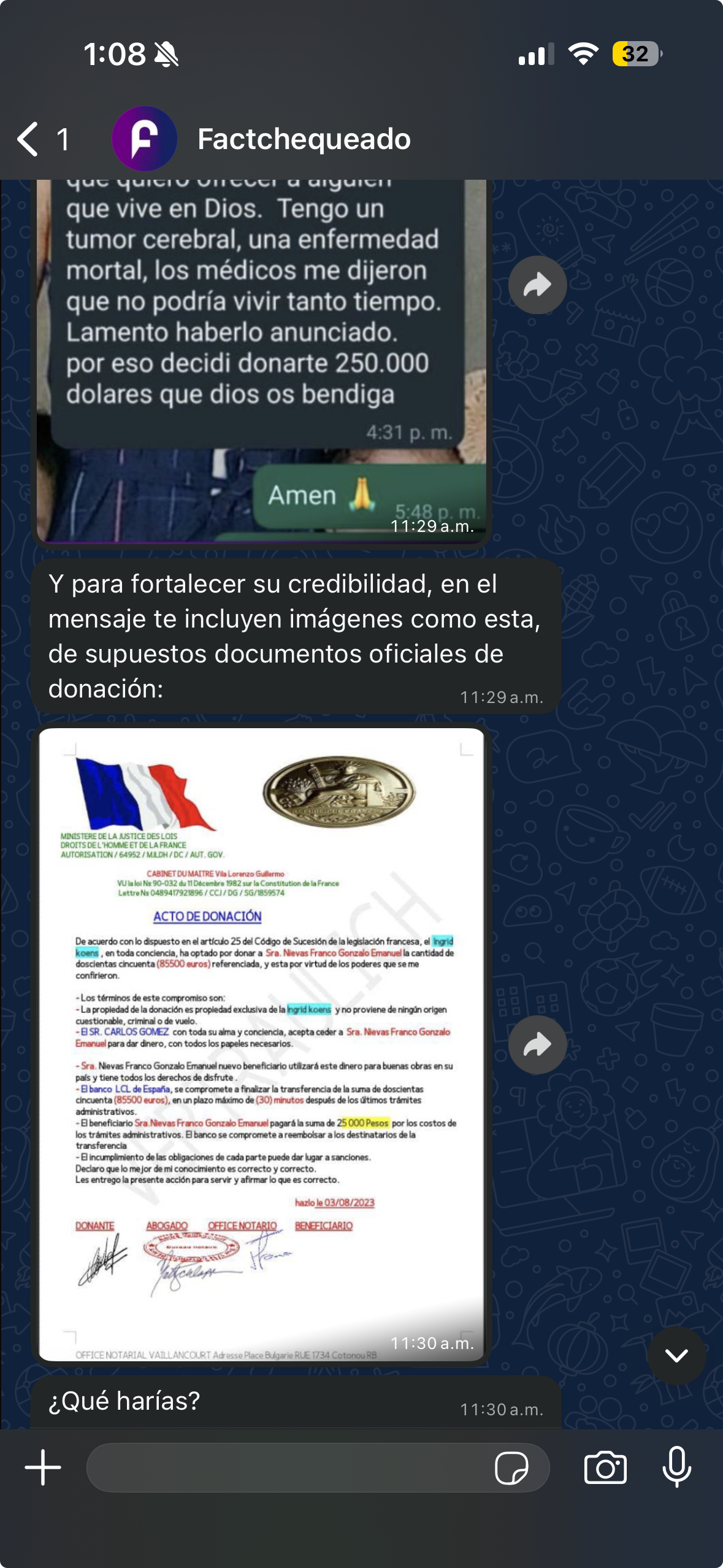

Numerous users have reported receiving a message supposedly sent by a French woman who, recently widowed and terminally ill, claims she wants to donate her fortune. To make the story believable, she attaches a supposed “donation certificate” featuring the French flag and official-looking signatures.

It’s a scam intended to get victims to hand over money to process the fake donation. This deception has become one of the most frequently searched topics in recent months in Factchequeado’s chatbot, according to Olivia Rivarola, its product and social media manager.

Similarly, the chatbot that Factchequeado uses to help people resolve doubts or verify content constantly receives fraudulent messages with supposed job offers or services for immigration procedures, Rivarola said. She added that stories related to digital scams are the most-read on their website.

Factchequeado launched this year Scam-Challenge, a free interactive WhatsApp course that teaches people how to detect online scams.(Photo: Screenshot of Factchequeado's chatbot)

These metrics showed the Factchequeado team there was a new informational need. That’s why they launched Scam-Challenge in October, a free interactive WhatsApp course that teaches people how to detect online scams.

“The product itself was born not only from studying and understanding the trend, but also from the internal data we have, both from visits to our articles about scams and from the queries we receive,” Rivarola told LJR.

Scam-Challenge is the second product in Factchequeado’s media literacy initiative on WhatsApp, following the launch of Fact-Challenge in 2024, an interactive course to identify and counter disinformation.

Although online scams are not purely informational content, it’s important for news outlets to get involved in efforts to counter those messages, said Laura Zommer, cofounder of Factchequeado.

Zommer said Latino communities and migrants are among the sectors most vulnerable to online scams in the U.S., which is why Scam-Challenge offers concrete examples of the main scams that Factchequeado has found affecting those populations: fake donations, fake immigration processes, phishing and fake job offers.

Scam-Challenge is one of several initiatives media outlets around the world are launching to counter the rapid rise of digital scams, accelerated by the growth of artificial intelligence, Zommer said.

“The people who used to ask us about disinformation are now asking us about scams,” Zommer told LJR. “And these initiatives are truly a response to the needs of the audiences they serve.”

Beyond news coverage that brings visibility to digital scams, explainer-type content like what’s shared in Scam-Challenge is very effective, Zommer said.

“This is not necessarily something only for fact-checkers,” she said. “My recommendation for any reporter, when they’re covering a particular case, is that in addition to telling the story, if they’re speaking with an authority, they should try to get them to explain whether it’s an isolated case or if they’re seeing others, what the patterns are, what the warning signs are.”

Educational materials that help people recognize and report fraud are essential for every journalist, said Beatriz Farrugia, a disinformation content and research analyst at Agência Lupa, the pioneering fact-checking organization in Brazil. That country recorded at least 281,200 electronic scam crimes in 2024, a 17 percent increase from the previous year, according to the Brazilian Public Security Yearbook.

“Many people are unable to identify a scam, and many others — when they do — don’t know what steps to take,” Farrugia told LJR. “It’s possible to file reports both with platforms such as Meta and Google, and with the authorities, depending on the country. In Brazil, for example, there are police units specialized in cybercrime.”

Farrugia said Agência Lupa runs various media literacy initiatives for both young people and older adults through its Lupeiros and Lupa 60+ programs.

Agência Lupa runs a page that verifies scams circulating in Brazil so people can quickly check whether suspicious content has already been debunked. (Photo: Screenshot)

Investigating the criminal networks behind these crimes, their implications and their consequences is another way to combat digital scams through journalism, Farrugia said.

“Conducting in-depth investigative reporting into the criminal networks requires identifying the domains involved, tracing the flow of funds, and attempting to identify those responsible for these operations,” she said.

Agência Lupa has a page dedicated exclusively to news content about scams, called “Será que é Golpe?” (Could This Be a Scam?). The team behind that site seeks to verify scams circulating in Brazil so citizens who receive suspicious content can check whether it has already been verified. In addition, Agência Lupa has its own WhatsApp channel where users can request verification of possible scams.

Training and developing basic skills to navigate the environments where digital scams occur is another way journalists can join the fight, Aguilar said.

SocialTIC offers online workshops on preventing digital scams and fraud, aimed at activists, human rights defenders and journalists. In these sessions, they teach how to use tools to verify certain types of scams, the different formats in which scams appear and the context in which these crimes are committed in Mexico, Aguilar said.

“In a context like Mexico’s, these scams reach much more sensitive issues: human trafficking, kidnappings, disappearances, trafficking,” Aguilar said. “I think becoming aware of the real scenarios of Mexico today and its digital landscape is very important.”

Aguilar said that although there are still no tools that are 100 percent effective at verifying online scams, trainings like those offered by SocialTIC help journalists sharpen their ability to detect them. In the digital scams workshop, participants also learn how to contextualize misleading content, as well as basic methods of data verification.

“The fact-checking part is very complex and can’t be automated yet, compared with checking, for example, a link or reviewing a file,” he said. “For these cases of disinformation, we provide fact-checking recommendations while recognizing they’re limited and require a much broader manual search and comparison of information.”

Farrugia added that it’s also important for journalists to stay on top of the most recent trends, as criminals constantly change their tactics.

“I recommend journalists pay close attention to the ads circulating on social media platforms and messaging apps, such as WhatsApp and Telegram,” Farrugia said. “Some signs you may be facing a scam include ads with sensational or exaggerated language, often promising major benefits, easy money, or quick profits.”

¿Has recibido mensajes de #WhatsApp con ofertas de trabajo increíbles?

CUIDADO ¡Podrían tratarse de #EstafasDigitales!

Échale un ojo a este post con tips y recomendaciones para detectar y protegernos contra este #AtaqueDigital.

https://t.co/QQVkua5im2 pic.twitter.com/4vpDe3WRoW

— SocialTIC (@socialtic) October 13, 2025

This article was translated with the assistance of AI and reviewed by Jorge Valencia.