The streets in Nicaragua are not the same as when massive marches began on April 18, 2018, when Nicaraguans came out in force to protest a reform proposed by the Daniel Ortega government that affected retirees' pensions. The Armed Forces strongly repressed the protests, and later it was known that first lady and vice president Rosario Murillo had given the order: "Let's go after them with everything."

A total of 328 people died during the crisis, according to monitoring by the Special Follow-up Mechanism for Nicaragua (Meseni) of the Inter-American Commission on Human Rights (IACHR).

Four years after the start of this relentless repression of social protests by the Ortega and Murillo regime — in which even publicly waving the national flag or wearing blue and white became a crime —, the streets of Nicaragua are now silent.

“There is a police state in which people cannot go out to protest. In which, if you are an opponent, you cannot carry out any activity or make any comment the Government considers to be against its State policy,” Jennifer Ortiz, co-founder of the news outlet Nicaragua Investiga, told LatAm Journalism Review. (LJR). “This is a jail. Nicaragua is a huge prison where all those inside have to submit to silence in order to continue living or be able to remain free to some extent.”

The level of repression, censorship, espionage, and intimidation is "beyond alarming," Pedro X. Molina, from news outlet Confidencial, told LJR.

“But if the population in general is in a precarious situation, the situation of independent journalism is much worse. In 2018, we still had national print newspapers, critical television programs, and more radio shows denouncing wrongdoing. Today we do not have a single printed newspaper with national circulation,” Molina said.

Periodista Pedro X. Molina portraying the President of Nicaragua Daniel Ortega. (Courtesy)

On Aug. 13, 2021, La Prensa, the oldest newspaper in the country and the only printed news still in circulation in Nicaragua, was raided. The police search was meant to investigate an alleged customs crime. The general manager of La Prensa, Juan Lorenzo Holmann Chamorro, has since been arrested and was sentenced seven months later.

Since 2018, the Ortega-Murillo regime has closed the offices of more than 20 local news outlets, including 100% Noticias, Confidencial and La Prensa, according to the Nicaraguan Never Again Human Rights Collective, according to the EFE agency. Channels 10 and 12, and Radio Corporación have recently felt financial pressure, according to the Collective.

More than 120 Nicaraguan journalists have been forced into exile since 2018, due to political persecution in their country, according to the human rights organization.

The Nicaraguan Congress approved in October 2020 the Law for the Regulation of Foreign Agents. With this law, the government can fine, sanction and intervene in the property and assets of an organization that receives funds from abroad, or even cancel its legal personality, if it determines that its activities deal with interests deemed contrary to Nicaragua’s internal and foreign policy.

Because of this law, the Violeta Barrios de Chamorro Foundation for Reconciliation and Democracy, founded in 1990, decided to suspend operations. It refused to accept the imposition of an "unconstitutional law" that required the foundation to register as a foreign agent, violating principles of freedom of organization.

"It is very difficult to continue operating under a law of this nature whose objective is to suffocate civil society, the independent and free voices that this regime cannot support," said the then-director of the foundation, Cristiana Chamorro, at a press conference announcing the closure of the foundation in February 2021, reported the Associated Press.

In 2021, the independent press faced another wave of violations and harassment. According to a "Report on Violations of Press Freedom 2021" by Voces del Sur, 2021 has been the most dangerous year for freedom of expression in Nicaragua, since the 2018 repression. There were 702 cases of abuse of power and violence against the press, a number that almost equals the 712 incidents of 2018, according to the report.

“It is quite difficult to do journalism from exile, because the people of Nicaragua, for the obvious reasons of repression, are afraid to speak…and if they speak to you, it’s anonymous,” Lucía Pineda, who now directs 100%, Noticias told LJR from Costa Rica.

Journalist Lucía Pineda with Jennifer Ortiz in a panel on Nicaragua during the 15th Ibero-American Colloquium on Digital Journalism. (Credit: Patricia Lim/ Knight Center)

Since Miguel Mora, founder and now former director of 100% Noticias, was arbitrarily detained again in June 2021 for running for president of Nicaragua, Pineda has been in charge of the news outlet, which only has an online presence.

Pineda explained that without joining efforts and resources with colleagues from Nicaragua Actual and Despacho 505, it would have been impossible to continue doing journalism. "Last year we covered voting in Nicaragua and among the three news outlets, we had a staff of more than 30 people."

However, they would like to further their training in order to strengthen their digital news outlet, to obtain a better ranking in search engines, since they had been a TV channel with 24-hours news prior.

Inside Nicaragua there is no independent journalism, Ortiz said. “Journalists right now cannot work from Nicaragua. I dare to say that 95% of media directors like me are in exile.”

"Journalists who are in Nicaragua work anonymously, in conditions of total secrecy, because it is a profession that the government has completely criminalized," Ortiz added.

Aníbal Toruño, director of Radio Darío, also directs his news outlet from exile in the United States. Since his radio facilities were destroyed by vandalism in June 2018, Radio Darío only provides information online.

"The practice of journalism is extremely difficult [in Nicaragua]. We use protocols to be able to continue broadcasting within the country, facing all the difficulties, persecution, raids on our collaborators, who are constantly watched and harassed, they and their families," Toruño said.

Without alliances with other news outlets, journalism in Nicaragua would not be possible, he said.

Molina, who is also in exile in the United States, is certain that Nicaragua and independent journalism are going through "the worst crisis in its history." However, "independent journalists, working underground, or from exile, remain committed to informing people and the international community about what is happening in Nicaragua." In his opinion, the propaganda and censorship attempts by Ortega and Murillo to alter the narrative of what is happening in Nicaragua "have totally failed."

There are 181 political prisoners sitting in Nicaraguan prisons, according to the latest update of the Mechanism for the Recognition of Political Prisoners in Nicaragua, published by the Spanish news agency EFE. Many of them have been imprisoned since 2018.

The journalists who have been detained as political prisoners in the Nuevo Chipote prison since mid-2021 are Juan Lorenzo Holmann Chamorro, general manager of the newspaper La Prensa; Miguel Mora, former director of 100% Noticias and former candidate for the presidency in 2021, Miguel Mendoza, Jaime Arellano, and Pedro Joaquín Chamorro.

Among the imprisoned journalists is also Cristiana Chamorro, former director of the Violeta Barrios de Chamorro Foundation for Reconciliation and Democracy and former candidate for the presidency in 2021, who is under house arrest.

Between February and March 2022, these six journalists received sentences of between 7 and 13 years in prison and millions in fines. Mora, Mendoza and Arellano were charged, among other things, with the alleged crime of conspiracy to undermine national integrity. Holmann and the Chamorro brothers were convicted of alleged money laundering and other crimes.

This is the second time Mora has been detained in prisons such as the old and new El Chipote, which are considered "torture centers." The first time, he was arrested on Dec. 21, 2018, after the police raided the headquarters of his TV channel, 100% Noticias. At that time he was arrested along with Lucía Pineda, then head of the news outlet. Both were kept in isolation cells, lacking minimum sanitary services, in isolation.

Six months later, Mora and Pineda were released under a controversial government amnesty.

“The international community and the Inter-American Commission on Human Rights (IACHR) in particular have expressed concern about the guarantees in these trials, about the manipulation of criminal law and we call emphatically for the release of all the people who are being arbitrarily prosecuted,” said the IACHR Rapporteur for Freedom of Expression, Pedro Vaca, referring to the sentences handed down against journalists who are political prisoners in Nicaragua, according to the Información Puntual news outlet.

Vaca also expressed his solidarity and support for Holmann. “A decision as authoritarian as it is premeditated, a judicial parody that confirms the aim of censorship and one more blow to press freedom in Nicaragua,” the Rapporteur said via Twitter.

Sé Humano (Be Human) is a social initiative by a group of volunteers who seek to raise national and international awareness of the situation of political prisoners in Nicaragua and their families. They seek to improve prison conditions so they receive a more dignified and humane treatment.

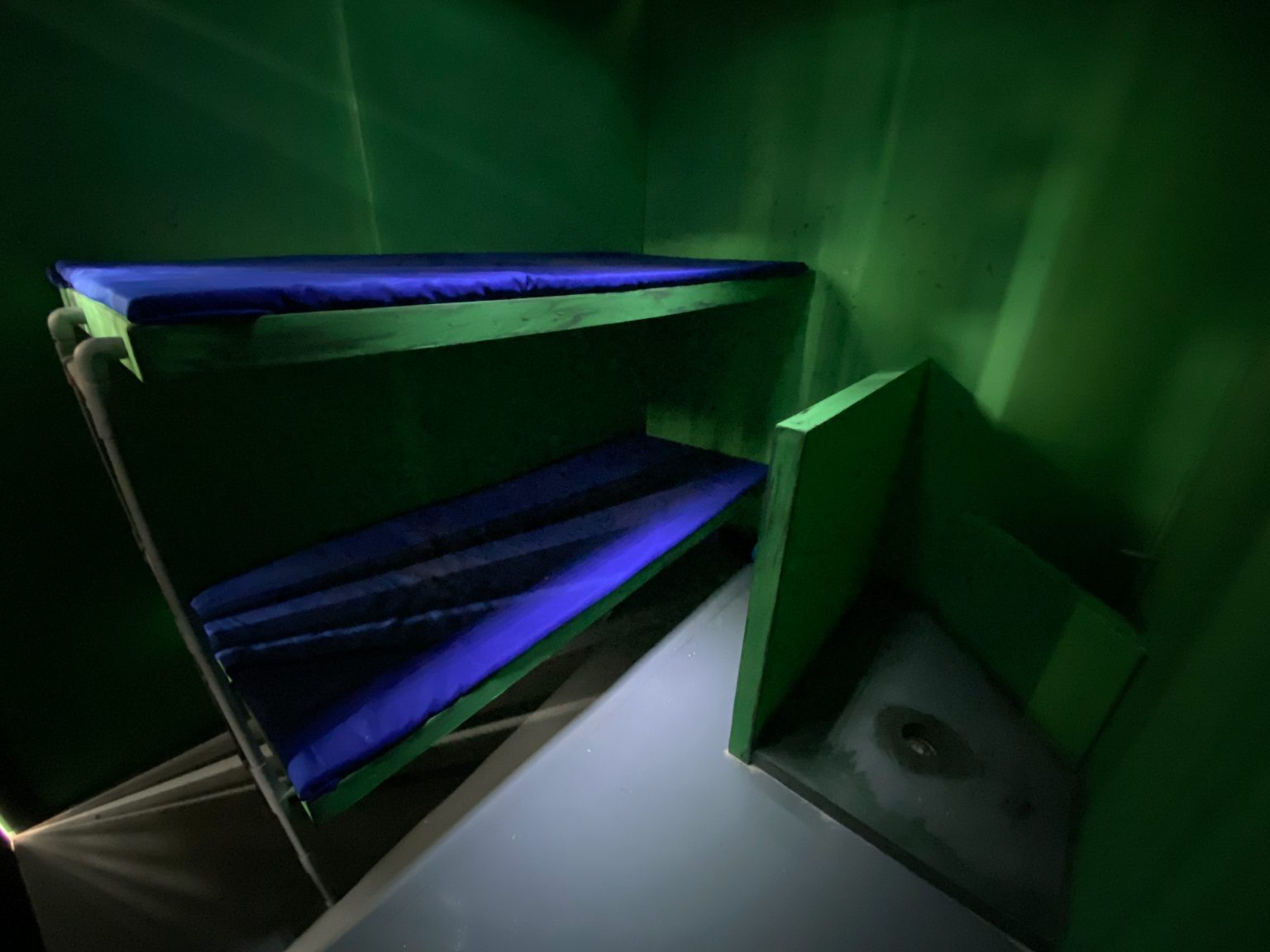

Exact replica of the punishment cell of the 'El Chipote' prison in Nicaragua (2.60 m long by 2.30 m wide). Exhibition of Sé Humano and Madres de Abril in the building of the National Assembly of Costa Rica, in November 2021, to make visible the conditions of political prisoners in Nicaragua. (Credit: Divergentes)

Camilo de Castro, volunteer of the Sé Humano campaign, confirmed to LJR that Holmann and Mendoza are now in isolation cells in El Nuevo Chipote, subject to constant interrogations, and are unable to receive regular visits by their families.

Holmann's health is deteriorating in prison, de Castro said, since he is not receiving the necessary postoperative heart medical treatment or tests he should’ve had for vision problems in one eye. Mendoza also has generalized body pain, and his family is very concerned, De Castro added, based on reports to which Sé Humano has access.

Some political prisoners are in underground punishment cells, so-called “little hell,” De Castro said. “They are like drawers, completely closed-off, with very high temperatures. The conditions are subhuman."

Sé Humano works on three fronts, De Castro said. Those are: high-impact public denunciation, lobbying governments in the region to advocate for political prisoners, and influencing public opinion, through art events and concerts that make visible the situation of political prisoners in Nicaragua.

On its website, there is an open letter addressed to Ortega, that anyone can sign, demanding the immediate release of political prisoners.

De Castro is a documentary filmmaker and worked for several years as a journalist at Esta Semana, a program directed by the journalist Carlos Fernando Chamorro. He, like many others, is in exile in Costa Rica. “It is really painful to see how they are hurting them. I think that the intention is to break them, to push them into a situation in which they cannot be functional; it’s about taking away their humanity,” said De Castro about the situation of political prisoners in Nicaragua.

In a recent press release, the Secretary General of the Organization of American States, Luis Almagro, called on the international community to "increase diplomatic pressure" on the Nicaraguan regime, and to show greater solidarity with political prisoners and their families.

“Political prisoners do not have enough access to sunlight. They do not have access to any reading material or writing tools. They do not receive correspondence. They do not receive adequate medical care, sometimes none at all. And the food is insufficient. Everyone there has experienced weight loss that puts their health at risk,” Almagro said.

For Ortiz, who as a journalist has been reporting on family members condemning the situation of the political prisoners, it is unlikely that Ortega will relax the measures applied to political opponents detained in El Chipote. According to the Nicaraguan Law of the National Penitentiary System, they should be taken to prisons within the prison system, but Ortega "would loose all control there and all possibility of continuing to exert this pressure and this political revenge."

“I’d say that we come from the future,” Toruño said, because they’ve already passed through what Venezuela passed through and what El Salvador is currently passing through. “Basically, one should learn from what is happening to us and I would highlight that journalism, the media in Nicaragua, despite so much havoc, siege, attacks, complications and jail, continue, to a very good extent, to generate good journalism from Nicaragua, in connection of course with the teams in exile.”

According to Molina, "letting authoritarianism win in any part of the world is a defeat for all."

Pineda asked Latin American journalists not to forget about them. “Don't forget us, keep writing about the situation in Nicaragua, about political issues, about the journalists who are in prison. Do not forget us."