The city of Ayacucho, located in southern Peru and with just over 215,000 inhabitants, became the scene of a tragedy that shook the country on Dec. 15, 2022. A protest that ended in clashes with security forces resulted in the death of 10 protesters, allegedly at the hands of members of the Army.

The protest took place within the context of the social turmoil that Peru has been experiencing since the attempted self-coup by former President Pedro Castillo and the ascent to power of the current leader, Dina Boluarte, on Dec. 7, 2022. The demonstrations have so far led to nearly 80 deaths, according to figures from Peru's Ombudsman's Office.

Following the massacre in Ayacucho, President Boluarte stated the deaths took place after an "avalanche of five thousand people" had attempted to enter the city's airport, which called for the intervention of the Armed Forces.

However, amidst a lack of transparency from the government, a pair of journalists from the investigative digital news outlet IDL-Reporteros, based in Lima, managed to show through forensic reconstruction work that the number of protesters had not exceeded 300, and that at least six of the victims had died from bullets fired by soldiers, away from the airport, contrary to the president's statement.

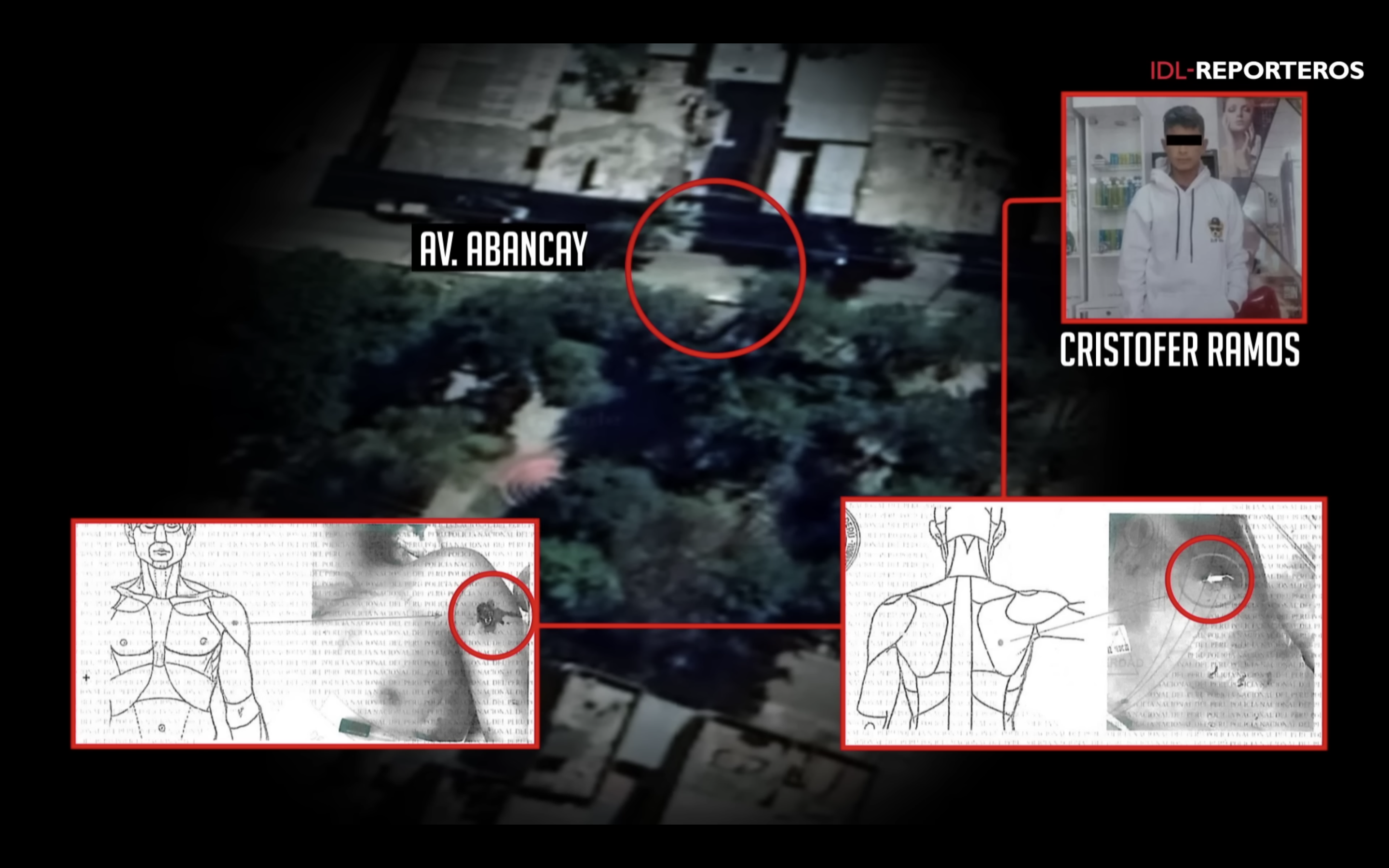

“Ayacucho: A homicide X-ray” was developed with video material from open sources, photos from the investigation file, and satellite images. (Photo: Screenshot of IDL-Reporteros)

This investigation was documented in the video investigation titled "Ayacucho: Radiografía de homicidios [Ayacucho: A homicide X-ray]," published on Feb. 12, which marked a milestone in the history of the digital news outlet and was recognized with the 2023 Gabo Award in the Image category during the last edition of the awards on June 30.

The investigation not only revealed undeniable information about what happened in Ayacucho, but also showed the usefulness of open-source reconstruction journalism in covering social conflict in Latin America.

"At the time, information coming from the regions was very murky. There were some videos, unconnected, and it wasn't clear what had happened. The Peruvian media here in Lima, in the capital, did not cover the case, did not investigate, they simply reproduced the president’s statements," Rosa Laura, journalist from IDL-Reporteros and author of the video investigation, told LatAm Journalism Review (LJR). "In response, our goal was to investigate what had transpired in order to reconstruct the events and find out exactly what happened during that day of protest on Dec. 15."

Laura and her colleague César Prado, her co-author, set out to make sense of the audiovisual information available on social media about the events in Ayacucho. They also obtained videos from families of the victims and local journalists who covered the events. Faced with an overwhelming amount of audiovisual material, the journalists knew they had to create a video investigation so readers could see with their own eyes how the events unfolded, leaving no room for doubt or interpretation.

In a news outlet where text had ruled, "Ayacucho: A homicide X-ray" meant the challenge of venturing into both an audiovisual format and a reconstruction narrative.

"This has been a pioneering investigation, not only for our news outlet but in general, because not many reconstructions had been done, nor had open-source material been used to reconstruct human rights violations in the country," Laura said. "Specifically for our outlet, an audiovisual investigation had never been done before. So, it was also a challenge to create the script, narration, and an idea of how to narrate the events."

The jury of the Gabo Award in the Image category, composed of journalists Eliza Capai (Brazil), Leiqui Uriana (Colombia/Venezuela), and Martín Caparrós (Argentina), praised the use of the reconstruction video format without falling into sensationalism or excessive use of technical resources, in order to tell a story the Peruvian State was trying to conceal.

The judges also encouraged other journalists in the region to experiment with the format to tell similar stories in their countries.

"'Ayacucho...' is a novel approach that does not revel in its novelty but rather employs it to tell what matters," the jury wrote. "Not only is it a great journalistic work but, above all, a working model that we want to propose to colleagues throughout the continent."

The 10-minute video narrative unfolds along a timeline that places the events over the course of more than eight hours of clashes on Dec. 15. Additionally, it relies on maps and geolocation to provide certainty about the exact locations where the murders occurred.

Prado played a key role in the geographical location of the events. Originally from Ayacucho, he facilitated contact with local journalists who had captured images and videos of the protests. Moreover, his knowledge of the city's streets and surroundings facilitated geolocating the conflict points.

Journalists Rosa Laura and César Prado received the Gabo Award 2023 in the Image category for the video investigation. (Photo: Screenshot of YouTube)

"It was crucial to know, based on very short clips of just a few seconds, where these situations were located. In other words, what had happened to some of the protesters," Prado told LJR. “We had short videos showing protesters being hit by bullets. Not only those who died but also the injured ones.”

Laura and Prado said they took as reference points other media's forensic reconstruction work on killings by law enforcement, such as La Silla Vacía (Colombia), which won the Gabo Award for Innovation in 2021 for their work "La Silla reconstructs how police killed the three youths from Verbenal," and Cerosetenta (Colombia), whose reconstructions "The second-by-second of the shot that killed Dilan Cruz" and "Seven hours of anguish at La Modelo," which were a finalist and a nominee for the same award, respectively.

They also reviewed similar works from international media such as The New York Times and The Washington Post (United States), as well as organizations like Bellingcat and Forensic Architecture (United Kingdom).

However, unlike these organizations that have extensive technology and teams, "Ayacucho: A homicide X-ray" was solely carried out by Laura, Prado, and a video editor.

"We thought that perhaps the work was a bit rudimentary, but it was very intense. It took weeks of intense work to publish it as quickly as possible with the resources we had," Laura said. She added that the investigative phase began just days after the massacre, and took three weeks.

Regarding the technology used, the journalists relied on Google Earth, not only to geolocate the events in the video investigation but also to figure out distances between different points using the application's measurement function. This helped compare the distance between the victims and the soldiers with the range of the weapons used by the latter.

By discovering that the Army had used rifles with an effective range of 600 meters [656 yards] that day, the journalists could calculate the location of the officers that fired from where the victims fell.

"We already knew where to investigate further, where to direct the investigation, based on the foundation we had. So, we found videos showing the soldiers exactly at that moment, shooting from the point we had calculated, towards the protesters. That helped a lot," Laura explained. "Also, César's [Prado] knowledge of the places, the streets, was essential to identifying where the videos had been filmed."

"Ayacucho: A homicide X-ray" shows images and data from autopsies of the deceased in the massacre on Dec. 15. Thanks to this information, the video investigation was able to establish more connections between the victims' wounds and the weapons used that day by the military.

However, the authors of the investigation did not obtain any official information from authorities, despite multiple attempts to contact the Public Prosecutor's Office. According to Prado, Peruvian justice authorities have maintained an attitude of opacity to date, not only in the Ayacucho case but also in other cases of violence during demonstrations in other cities in Peru.

"Both the Executive and the Public Prosecutor's Office have remained absolutely closed to providing any information. They haven't even respected something that is very useful for journalists and has been in practice for a long time, which is the Transparency Law. We requested information from the Police, the Army, and other institutions about what happened that day, and the only response we received was that the information was classified or confidential, and nothing more," the journalist said.

In addition to gaining access to the Public Prosecutor's Office's investigative folder and documents from autopsies and ballistic tests, through lawyers of the victims' families, Laura and Prado consulted forensic anthropologists for their technical opinion on what they could see in each of those documents. Thanks to this information, IDL-Reporteros became the first news outlet to reveal the identities of the alleged shooters.

"With that, we closed the circle completely because it matched to and corroborated what we’d found in the videos," Laura said.

IDL-Reporteros was the first news outlet to reveal the identities of the alleged shooters of the Ayacucho killings. (Photo: Screenshot of IDL-Reporteros)

The team also obtained crucial information from victims’ families that complemented the open-source data. Families’ urgency to find those responsible for the murders motivated them to collaborate with the journalists since, up to that point, no one had been arrested, and there had been no significant progress in the investigation. This situation remains the same to this day, even though, in June of last year, a special team from the National Prosecutor's Office ordered the Peruvian Judiciary to hand over information classified by the Army as “reserved.”

"The families supported us because they knew about IDL's work. IDL has already earned a good reputation, and when we told them what we were doing, they knew we had a lot of information and that we were handling it correctly, ethically," Laura said. "Moreover, we were open with what we had. We could share with the families the information we had and what we were missing."

One of the impacts of "Ayacucho: A homicide X-ray" is that the video was included as evidence in the investigation file when the case was under the jurisdiction of the local Public Prosecutor's Office in Ayacucho. Additionally, after winning the Gabo Award, the case gained international visibility, which the authors hope will result in increased pressure on the authorities to carry out justice.

However, the forcefulness of the video investigation has also brought out negative impacts to IDL-Reporteros. After its publication, the news outlet has been targeted with both online and physical attacks by violent groups disguising their aggression as a defense of institutions such as the Police and the Army, according to the journalists.

"After the work was released, I remember they went to the IDL offices to stage a protest. Recently, they even threw bags of excrement at IDL [offices]. Also, when a journalist aired our video on Ayacucho on her show, they went to her house to insult and defame her. So, it’s been a constant attack," Laura said.

The attacks date back several years, since IDL-Reporteros began publishing revelations about the involvement of Peruvian officials in the Lava Jato case. Although the aggressions initially started in the digital realm, they soon escalated to physical actions, particularly against Gustavo Gorriti, the director of the news outlet, to the point that on July 24 of this year, the Inter-American Commission on Human Rights (CIDH) granted precautionary measures to protect Gorriti after determining he is in an imminent risk situation.

Nevertheless, Gorriti and his team's response to the attacks has been to conduct further investigations with the necessary rigor to make them irrefutable and have an impact on Peruvian real life. "Ayacucho: A homicide X-ray" is an example of this. The format of the video investigation allowed them to show things as closely as possible to how they happened, not based on a journalist's observation or witnesses' memories, the authors agreed.

"I believe the work is so precise, we have verified it so many times, and it shows undeniable facts. No one can refute what the images show," Laura said. "We do believe that we managed to deliver a high-quality investigation to the public that had repercussions in society."

Banner: Ministerio de Defensa del Perú, CC BY 2.0; Candy Sotomayor, CC BY-SA 4.0, via Wikimedia Commons