With each new election, a certain story is mandatory in Brazilian newsrooms: how rich the candidates declare themselves to be. This is because they all need to declare their assets to the Electoral Court and this data is publicly accessible on the Internet.

This is only possible because the Brazilian Electoral Court makes available this and other data on all politicians running for public office in Brazil, from the President of the Republic to city councilor. This way, voters can find out more about the candidates, including information about electoral donations and campaign spending.

The system is so simple that in just two minutes, for example, it is possible to discover that President Luiz Inácio Lula da Silva declared total assets worth BRL 7,423,725.78 when he ran for office in 2022. In 2006, when he ran for reelection, his assets totaled BRL 839,033.52. Lula, therefore, became eight times richer in 16 years.

But it was not always this way. Until 2004, the Electoral Justice system was not on the internet, which made this type of search practically impossible. Furthermore, in the absence of a protocol, which would only be established years later with the Access to Information Law, obtaining public data was almost impossible as it depended on the good will of the public servant on duty.

Reports from the series “Os Homem de Bens da Alerj” showed 20 years ago how rich Rio’s state deputies were and inaugurated a new format of journalistic investigation that continues to this day in Brazil. (Photo: Reproduction of the newspaper O Globo from June 20, 2004)

Twenty years ago, on June 20, 2004, a series of reports published by the Rio de Janeiro newspaper O Globo began to change this story. A group of seven journalists had access to the declaration of assets that the deputies elected to the state Legislative Assembly (Alerj, for its acronym in Portuguese) reported to the Regional Electoral Court (TRE-RJ). Thus, they were able to check the evolution of wealth of each state deputy, something unprecedented until that point in journalism in the country.

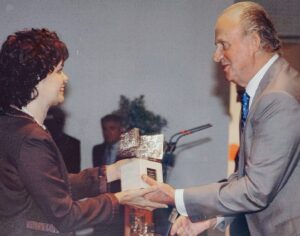

The series of reports “Os Homem de Bens da Alerj” (in Portuguese simultaneously meaning “The Good Men of Alerj” and “The Real Estate Men of Alerj”) revealed the incredible enrichment of 113 deputies while in office. Twenty-seven increased their assets by more than 100% between 1996 and 2001. There were cases of growth of more than 1,500%. The innovative work earned the authors the Esso Journalism Award and the King of Spain International Journalism Award, among others.

At the time, data relating to politicians' assets were kept on paper in a physical file at the headquarters of the Regional Electoral Court of Rio de Janeiro. The president of the court granted the reporters access to the site. In the following elections, the data began to be published on the internet and the method of crossing data inaugurated by the Globo team became routine in other newsrooms in the country.

And why hadn’t anyone done this before? Although the data was public, the absence of legislation regulating access to information represented a significant obstacle. The bureaucratic and uncertain process for obtaining authorization from the appropriate authority discouraged journalists from seeking this information. Furthermore, even after obtaining authorization, there was no guarantee that the data would result in a journalistic article. Globo's work showed that it was worth investing time and resources in this kind of investigation.

“We didn’t have the real dimension of what we were doing. It took eight months of investigation. In the end, it was a legacy for journalism and an example of transparency that led to a transformation outside the newsroom,” journalist Angelina Nunes, who led the team of reporters at the time, told LatAm Journalism Review (LJR). She is currently in charge of the Tim Lopes Program at the Brazilian Association of Investigative Journalism (Abraji).

It seems incredible, but in 2004 data journalism did not yet have the advanced and automatic tools we have today. Then-reporter Dimmi Amora, now director and founder of Agência Infra, had the Herculean mission of tabulating the data obtained, transforming a pile of disorganized papers into an Excel spreadsheet with thousands of lines. It was a job that required a lot of patience and attention to detail because all data entry was done manually. The effort, however, exceeded all expectations. With the organized data, journalists were able to identify patterns and trends that were previously invisible.

Angelina Nunes receives the King of Spain Award from King Juan Carlos (Photo: Personal archive)

"One of the things we did was compare some economic indices at the time. We analyzed period values, inflation, treasury bond yields, among other things, to have a parameter and say that a specific group of deputies had a growth of wealth far beyond what would be normal for an ordinary person," Amora told LJR.

Reporter Maiá Menezes, who is now deputy editor of politics at Estadão, was responsible for comparing the raw data with the real lives of the deputies who had grown most wealthy while in office, traveling through his electoral districts. She discovered that one of the most prominent deputies at the time had built a mansion on declared land for a fraction of its real value. The situation suggested that the deputy could have underestimated the value of the land in the public declaration, possibly to pay less taxes or to hide part of his real assets.

“It was a jungle (of data) and we were the pioneers, combing through information. The traditional investigation continues to be essential, that is, going to the streets without relying solely on the official versions. I view data journalism with immense respect, both what is practiced within newsrooms and what is developed in new initiatives and journalistic collectives. But what fell to me at that moment, for me, continues to be, the diamond of production for anyone who is a reporter, which is going beyond the numbers, investigating, talking to people, checking the addresses mentioned in the documents and seeking information directly,” Menezes told LJR.

Nunes remembers that the team worked for four months collecting data and documents before actually pitching the story to the newspaper. This work took place in the few spare hours between one investigation and another on a daily basis. Only when the spreadsheets showed the unequivocal journalistic potential of the data were the reporters able to officially dedicate themselves to the investigation.

“We wouldn’t be able to come up with an idea for a story without having at least one very strong indication. From the moment Dimmi puts everything in the table, then the stories emerge, and we pitch them to the editors. It is at this moment that we start to rotate among ourselves, to handle the investigation and day-to-day coverage,” Nunes said.

Lasting legacy

One of the challenges of the “Os Homens de Bens da Alerj” series of reports was not to get carried away by the initial excitement with the first discoveries and to remain calm to check the data and evaluate each case carefully. Although many cases seemed strange and raised suspicions of illicit enrichment, reporters discovered that some were in fact compatible with the politicians' wealth.

“They were extremely careful not to accuse anyone. At no point does the reader encounter the word illicit enrichment, they talk about wealth evolution. And they received a response from everyone mentioned, which is quite rare in a case like this,” journalist Marcelo Soares, one of the pioneers of data journalism in Brazil who served as an informal consultant to the team, told LJR.

Flavio Pessoa, Maiá Menezes, Alan Gripp, Angelina Nunes, Dimmi Amora, Carla Rocha and Luiz Ernesto Magalhães receive the Esso Journalism Award in 2004. (Photo: Personal archive)

“We established that, as the topic was very sensitive, any information needed to be cross-referenced with three sources to avoid errors, such as [name] homonyms, for example, and others. In the end, we published 70% of the total information we obtained out of diligence and care,” Nunes said.

The report triggered a movement to open up information on several levels. Abraji began a campaign to create a law that would ensure the transparency of public documents. This was fundamental for the conception of the Access to Information Law (LAI), which was enacted in 2011 and guarantees all citizens the right to request and obtain information from public bodies and entities.

“It was groundbreaking reporting and continues to be so today. The team was able to show what the data is for and apply it in practical life. They combined the best investigation methods. They built a complete database that didn't exist, and checked all the information rigorously,” Soares said.

“What we did 20 years ago was part of the evolution of democracy. Data considered absolutely public and essential was closed and we managed to make an effort so that everyone had access,” Menezes said.

In addition to Nunes, Amora and Menezes, reporters Alan Gripp, Carla Rocha, Flávio Pessoa and Luiz Ernesto Magalhães also participated in the investigation.