Reading a journalistic investigation into the execution of civilians by the military isn't the same as hearing it spoken by its author in front of a military museum that is an icon of the power of a country's military.

That's what happened on Sept. 25, during the first journalism tour through the streets of Bogotá conducted by Rutas del Conflicto, the digital investigative journalism outlet specializing in the Colombian armed conflict.

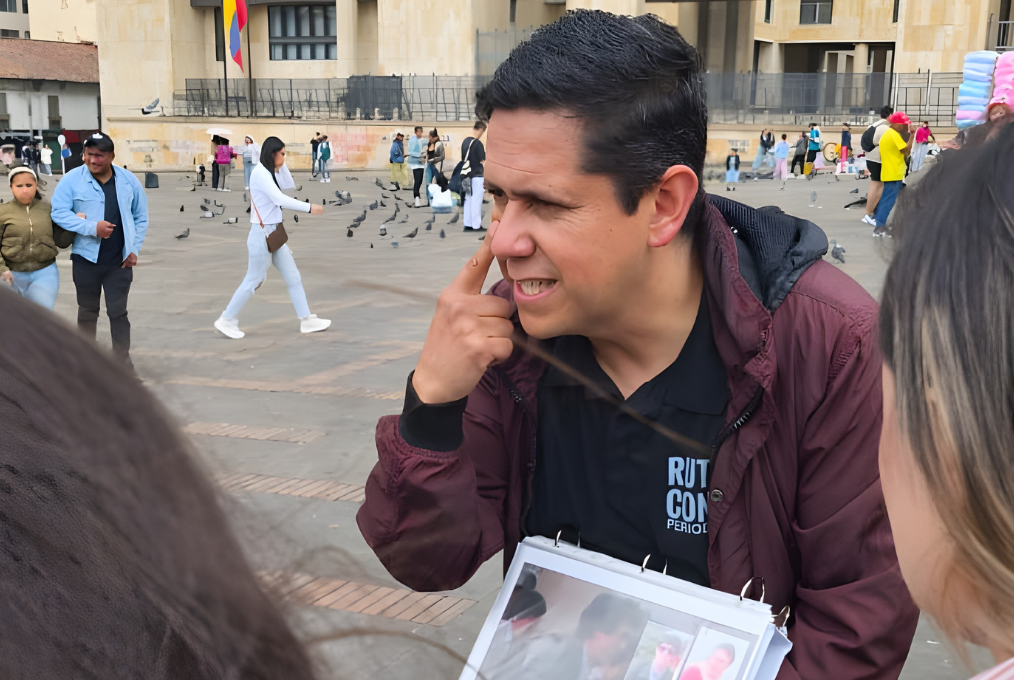

For nearly an hour and a half, a group of 15 people toured the iconic La Candelaria neighborhood with guide and journalist Óscar Parra, director of Rutas del Conflicto, while listening to the findings of his report, "The electricity business that financed the battalions responsible for the 'false positives' in Eastern Antioquia."

Rutas del Conflicto’s journalism tours include stops at sites that symbolically illustrate elements of the reports being discussed. (Photo: Courtesy Rutas del Conflicto)

The investigation reported that energy companies financed military battalions responsible for the murder of civilians who were falsely registered as guerrillas killed in combat.

“A tremendously symbolic moment on the tour is [when we stop] in front of Colombian soldiers guarding the Military Museum, standing there and pointing out that Colombian soldiers committed these crimes,” Parra told LatAm Journalism Review (LJR). “At the highest point in the city is the first electrical substation, a very old facility, and we show it as a symbol of the electricity companies that gave money to the Army at the time.”

Although the events in the report occurred between 2002 and 2008, they have gained relevance in recent years due to the activities of the Special Jurisdiction for Peace, the justice and reparation mechanism for the Colombian armed conflict.

“There's still a large segment of the population that I think doesn't understand the scale of these crimes. So it seemed important to us that people from the city environment, young people, could use that urban environment to understand the story,” Parra said. “There are conditions around that area of Bogotá that demonstrate the country's economic and political power, which we use to tell this story.”

The tour is a new way in which Rutas del Conflicto aims to convey its journalistic work directly to the people, this time by leveraging tourism. The strategy allows the outlet to strengthen a niche audience, reinforce its sustainability and boost its founding efforts to promote historical memory about the armed conflict in Colombia, members of the Rutas del Conflicto team said.

The project is part of Rutas en Vivo, a series of initiatives in which journalists present their investigations to the public in person in the form of stand-up shows or performances. As part of Rutas en Vivo, the media outlet had previously organized tours, albeit focused on ecological or historical memory issues.

The journalism tour on the "false positives" also includes stops at sites such as the Presidential Palace in Nariño, the headquarters of Congress, an iconic market and Bogotá's first residential complex. These are points that, according to Rutas del Conflicto, symbolically illustrate elements of the investigation.

“It's outdoor journalism,” Juan Carlos Contreras, a photojournalist and one of the tour guides, told LJR. “It adheres to some tourism regulations, but it's live journalism.”

When Rutas del Conflicto began organizing historical memory tours about events like “El Bogotazo”—the 1948 riots in the Colombian capital following the assassination of populist leader Jorge Eliécer Gaitán—or the 1985 guerrilla takeover of the Palace of Justice, it found that people were interested in learning more about the armed conflict but rarely read the extensive investigations published by media.

“Many people simply don't have the time to read an investigative text of 30 pages or more,” Parra said. “Sometimes there are pages with an average reading time of one minute or a minute and a half. In other words, very few people sit down to read the entire investigation.”

Faced with this reality, Parra and Contreras considered ways to take the investigative journalism of Rutas del Conflicto beyond the screen. They wanted to integrate elements of tourism, an activity they both enjoy.

“It's a very personal kind of journalism, one-on-one with the people. It's having the people who do these reports there, and you can ask them how they were done, the context, so you don't just rely on what's in the text,” Ginna Santisteban, director of special projects for Rutas del Conflicto, told LJR. “Having these one-on-one conversations allows us to better understand the results of the investigation. Ultimately, that's the goal of the journalism we do.”

Parra said that this year more than a thousand people have attended Rutas del Conflicto’s stage performances. Although these types of live journalism activities have limited audiences due to space and logistics—the tours, for example, are limited to a maximum of 30 people per walk—in these spaces, it is possible to more clearly see how the public understands the findings of the investigations, something that online metrics don't always reflect, he added.

View this post on Instagram

“I would rather have a thousand people listen to me narrate a report, talk, interact with me than, I don't know, a thousand likes,” Parra said. “One definitely doesn't compare to the other.”

The journalistic tour about "false positives" was attended by people invited through Rutas del Conflicto's social media channels, most of whom were followers of the outlet, Parra said. Some of them had even participated in other Rutas en Vivo experiences, he added.

For the media outlet, this is an indicator that these types of initiatives have helped consolidate an audience community that enjoys consuming stories in this format and is willing to pay for them.

“By developing this idea of person-to-person journalism, we've been building a niche,” Parra said. “I think it's an innovative approach for people and helps us strengthen our niche, helps us fund our business, and helps us build a community.”

In addition to being a photojournalist, Contreras runs the Mil Estaciones tour operator, which Rutas del Conflicto partnered with to organize the walks. Thanks to this partnership, it was possible to facilitate the logistics of each tour and comply with regulatory requirements.

“It's an activity regulated by tourism rules,” Contreras said. “We have to pay an insurance policy for attendees. And second, there are some attractions and establishments where we have to apply for permits. We also have to speak with the tourism police so they are aware of what we’re doing.”

Attendees of the first walk paid 10,000 Colombian pesos ($2.60 USD) for the tour. The historical memory tours cost 20,000 Colombian pesos ($5.20 USD).

However, Rutas del Conflicto obtained funding from the Heinrich Böll Foundation to conduct free journalism tours for students during October and November.

“There are funders who are very pleased with the fact that the investigation is being disseminated directly and personally to a focused group of students,” Parra said. “We're going to take 200 college and university students on the full tour to tell the story.”

The foundation, which also funded the report on "false positives," has shown interest in organizing tours to share other Rutas del Conflicto investigations, Santisteban said. This contributes to strengthening its sustainability.

“We struggle a lot to get funding to be able to tell our stories. We believe that the more people know about what we do, about what we've been able to investigate, the better,” Santisteban said. “It's a way to further our investigations, to make ourselves more visible, and to find allies who will help us with funding, who will appreciate the innovative ways of telling stories that we offer.”

Tres empresas eléctricas entregaron +$40 mil millones de la época (2002-2008) a la IV Brigada y batallones como el BAJES, responsables de la mayor cantidad de crímenes de estado conocidos como ‘falsos positivos’ en Colombia, según @JEP_Colombia.https://t.co/AjerjOgLh4 pic.twitter.com/XFT1dMh0Xi

— Rutas del Conflicto (@RutasConflicto) September 11, 2025

The idea of live journalism from Rutas del Conflicto is to tell stories that generate an experience around the media outlet's journalistic practice, Santisteban said. These experiences often end up having an emotional impact on the audience.

To achieve this effect, the team must create a script that interweaves the main findings of the investigation with the historical and symbolic context of the places visited, Santisteban explained. In addition, the narrative is complemented with visual material, ranging from historical images to infographics that illustrate the report on the website, Parra added.

“The fact that you tell the story in such a personal way, showing them photographs of the victims, trying to get people to remember what their life was like at that time, what the city was like, I think it has a huge impact on them,” Parra said. “This allows you to reach a person's emotions much more deeply than if someone simply reads an article in a more conventional way.”

As with other Rutas en Vivo experiences, the tours open opportunities for attendees to ask questions and for journalists to share anecdotes about the investigation, Parra said.

The journalist said they plan to occasionally invite relatives of victims of the murders covered in the report to share their experiences during the tours.

“There's a much more experiential aspect to the fact that we're going to have victims who can join the tour and contribute from their personal experiences,” Parra said. “The idea is to do it as we do in all live journalism exercises, like in theater, where we've always tried to bring in a source who can tell their story firsthand to the audience. That really surprises people.”