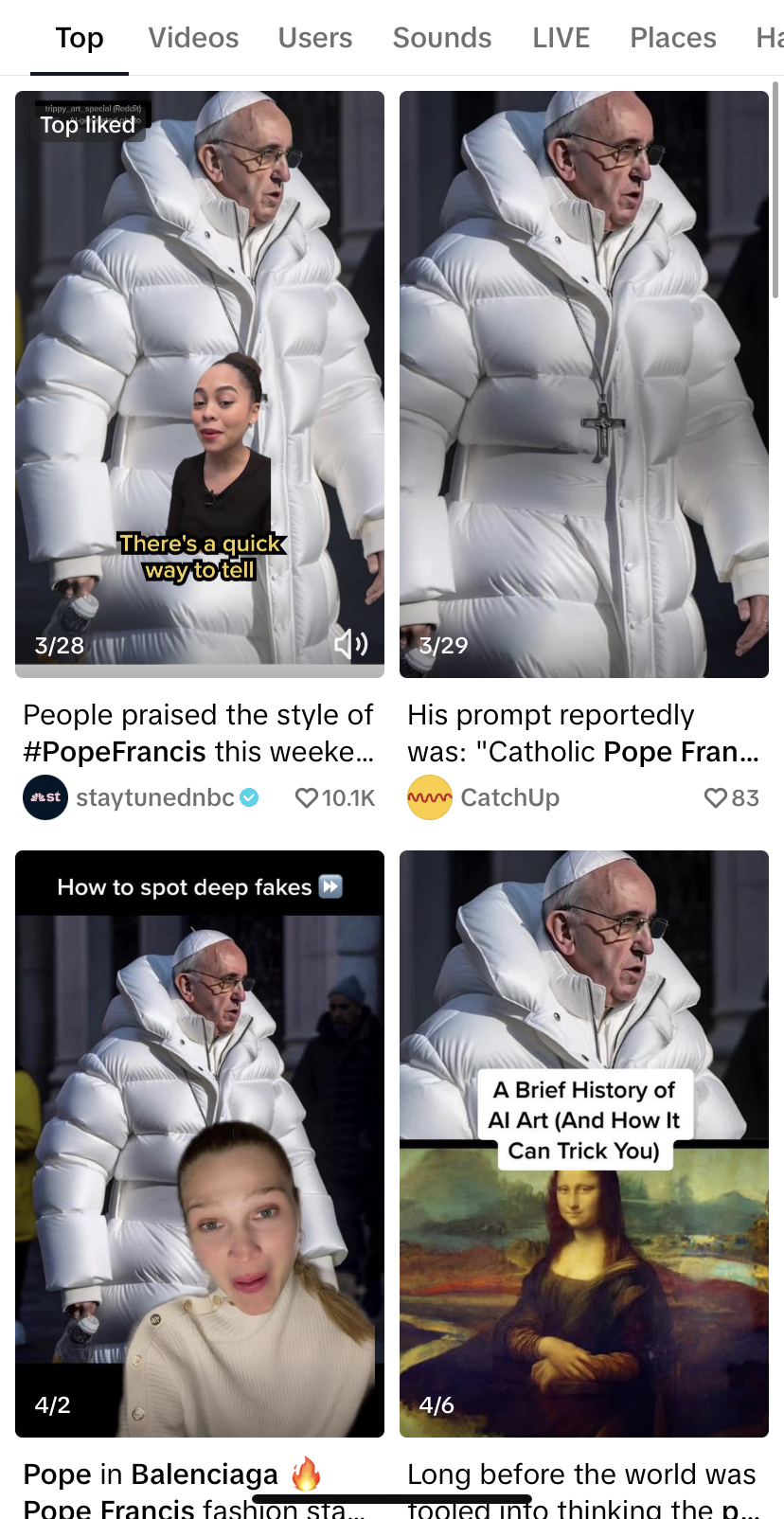

An image of Pope Francis wearing a white Balenciaga puffer coat and a series of photographs of former U.S. President Donald Trump being subdued by police officers caused controversy in the media and social networks in March of this year. It wasn't long before fact-checkers around the world made clear these were images created by the generative artificial intelligence application Midjourney, which creates images from natural language descriptions.

Fake and hyper-realistic materials such as the ones mentioned above have been a source of red flags due to their high capacity to generate disinformation and manipulate public opinion. For several years, fact-checkers and technology companies have been trying to find a convincing answer to counteract the power of deepfakes, as audiovisual pieces created by artificial intelligence that seem authentic but are false are known.

A project called the Content Authenticity Initiative (CAI), led by software company Adobe, seeks to combat disinformation through the widespread implementation of a technology standard that provides information about the origin and alterations of digital content on the Internet.

The initiative seeks to engage various industries, including media, technology companies and device manufacturers, around an open source protocol with interoperability between multiple tools.

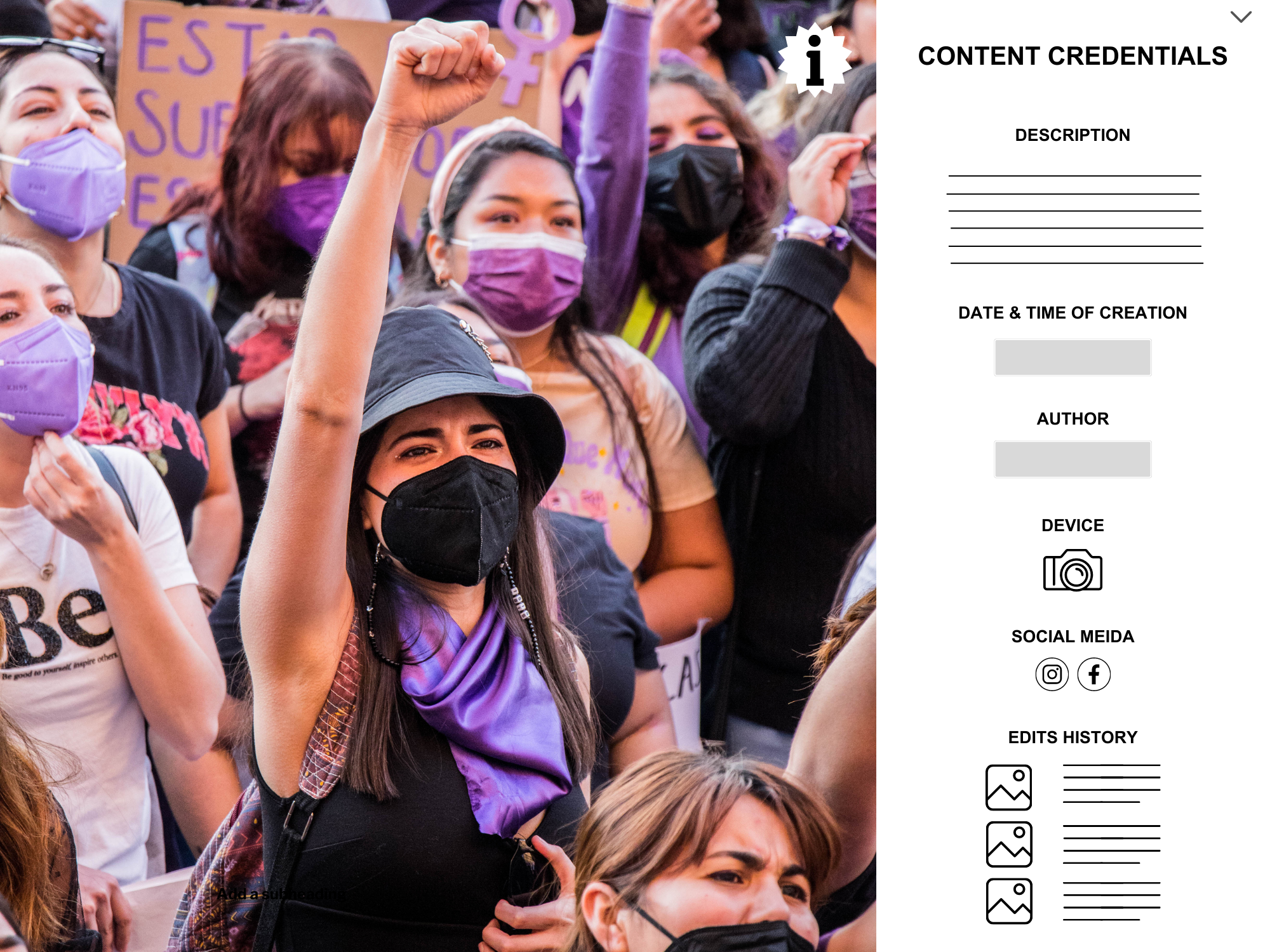

Representation of how a photo's content credentials would be displayed, according to the Content Authenticity Initiative's description. (Photo: Norma Galván via Canva.com)

"With the advent of artificial intelligence, came the possibility of a large proliferation of false information that is even more difficult to detect," journalist John Reichertz, CAI consultant for Latin America, told LatAm Journalism Review (LJR). "What the initiative seeks is to try to give the public elements with the idea of transparency, which is a value of journalism, so that they can determine whether an image, a video recording and eventually a document, is real or false."

The initiative's open source technology standard will enable "content credentials" to be embedded in digital material. That is, provenance data that provides users with tamper-proof contextual information about changes made to content over time, from its gestation on a device to its publication on a news outlet or platform, including data about its identity, the types of edits used and modifications made.

The CAI proposes that, once the standard is implemented, each image and video on the Internet will include an information symbol (i) on the upper right corner, which, when clicked, will show the data of provenance and alterations. In a later version, the tool will even allow viewing the different versions of each piece of content, from the original file to the published file, Reichertz said.

"It's very similar to when you buy a can of tomatoes at the supermarket and you see a can that says only 'tomatoes' and has no other information, and you see another one that has a nutrition label with a package date, expiration date, that in addition to tomatoes it has water, sodium, colorants, preservatives, and so on," he explained. "You're almost certainly going to grab the can that has information on it. It's the same concept in that you're consuming a product and you want to know more about where it comes from and what the contents are like."

This year's images of the Pope and Trump were not the first deepfakes to go viral. In 2017, researchers at the University of Washington created a fake video of Barack Obama from an artificial intelligence technique that "learned" to accurately replicate the former president's movements as he spoke.

The difference is that, nowadays, generating hyper-realistic fake images does not require a group of artificial intelligence experts. Almost anyone can create them in applications such as Midjourney, Dall-E or Stable Difussion, which could lead to a point where you don't know how to distinguish which content on the internet is real and which is not.

"Before, to fake [material] you had to understand Photoshop or some other program, you had to have some skill and also invest in a program," said Reichertz, who was Latin America editor for Reuters and EFE agencies. "Today anyone can do it and that has several implications."

One of those implications is that people's distrust of the media could grow even more, the journalist said. According to the most recent edition of the Reuters Institute's Digital News Report, more than half of global respondents find it difficult to distinguish between real and fake news on the Internet, which, in an information ecosystem polluted with altered content, ends up affecting people's credibility in all sources of information, including the news media.

"People have a lot of trouble distinguishing between what is real and what is not real. When you start to doubt what is real and what is not real, you start to question everything. And that for the media industry is, in my opinion, an existential crisis, because the highest value of the journalistic product is your credibility," he said.

At the moment, CAI is placing great emphasis on implementing its technology standard in photography. However, it is expected that in the coming years all types of digital content will include source and alteration data.

Although the initiative is still in its early stages and no photographic device manufacturer has yet implemented it, two camera brands — Nikon and Leica — have committed to implementing the CAI code in their equipment most commonly used by professionals, Reichertz said. Meanwhile, Truepic, a company specializing in digital content authenticity, is developing software to enable the technology standard to work on smartphones.

In addition, Adobe has already included the content credentialing feature in a Beta version of Photoshop, one of the most popular image editing programs, as well as in Firefly, its generative artificial intelligence product.

The Content Authenticity Initiative seeks to implement its technological standard throughout the entire process of digital content. (Graphic: César López Linares)

Although all international agencies in the West have joined the CAI, including AP, Reuters, AFP, EFE and DPA, Reichertz said it is not yet clear when they will start integrating content credentials into the images they send to the media.

However, in the very near future it will be possible to start including credentials from the editing stage onwards. The team behind the initiative is working to bring media content management system (CMS) developers on board, with the aim of achieving full interoperability of the technology standard throughout the process.

"What you could do today is from the editing on down, get [the credentialed file] to go through the CMS and get it published in the news outlet, so that the moment agencies start sending credentialed information, it flows right through the system automatically," Reichertz said. "Or when cameras and smartphones start having the credentials from the get-go, that flows through the whole system."

CAI content credentials are antecedent to metadata from photographs taken with digital cameras and smartphones, which commonly include image date, location, device, measurements, among others.

The difference is that while the metadata of current digital photos is lost once the material is edited or exported, the CAI credentials are securely linked to the file and even if attempts are made to alter them, these attempts will also be reflected in the metadata.

"If you take a picture with your smartphone, you can see where you took it and at what time. But that's not secure information, it's not linked in a secure way to the photo file and the data can be deleted or changed," Reichertz explained. "In this model, it's all secure: It's encrypted and the information about the photo and where it came from are intimately linked so you can't alter that information."

The CAI tools for digital content authenticity and provenance are open source and are available for any company, media or developer to use to create applications or integrate them into their systems. Although they have no cost, they require an investment for their implementation. And, above all, they require a collaborative effort among device manufacturers, software developers, media and social networking platforms, Reichertz said.

What CAI representatives are currently seeking is to create a sense of urgency among all stakeholders in the digital world, introduce them to the initiative and promote the use of the technological protocol.

"There has to be overwhelming pressure for all players in the digital ecosystem to agree to include this as a staple in their service or products," Reichertz said. "That's the goal, that this is not a nice-to-have option. The pressure coming today is that this should be part of the basic service, without an additional cost, and that we all agree."

CAI has more than 1,300 members worldwide, including world-renowned media outlets such as The New York Times, The Washington Post and The Wall Street Journal.

The initiative arrived in Latin America in September 2022, when Reichertz and his team began presenting the project to major news groups and media associations. As of July 2023, more than 50 Latin American media outlets and organizations have endorsed the initiative. They include the Asociación de Entidades Periodísticas Argentinas (ADEPA), the Associação Nacional de Jornais (ANJ), the Asociación de Medios de Información de Colombia (AMIC) and the Alianza de Medios de México.

The photo of Pope Francis wearing a luxurious coat caused controversy on social media for being an image created by the generative artificial intelligence site Midjourney. (Photo: Screenshot of TikTok)

Among the Latin American media that have joined are fact-checking organizations such as Ecuador Chequea (Ecuador), ColombiaCheck (Colombia), Verificado (Mexico), Chequeado, Proyecto Desconfío (Argentina) and Comprova (Brazil), as well as news outlets such as El Tiempo, El Espectador (Colombia), Infobae (Argentina), El Mostrador, La Razón (Chile) and Perú21 (Peru), among others.

At this stage, the mission of CAI's representatives in Latin America is to make the initiative known and gain the support of the region's media. For the time being, the initiative has created a Discord channel where members can comment on technical issues and where discussions about the project are being held.

According to some Latin American fact-checker members, although CAI will not replace their verification work, it will complement their traditional strategies to fight false information.

"Solutions to combat disinformation are multiple and collaborative and have had little effect when applied in isolation. So, we seek to support all initiatives that can collaborate with improving the information environment," Sérgio Lüdtke, editor-in-chief of the Comprova Project, a coalition of 24 news outlets that verify false content in Brazil, told LJR. “We understand that we could not be left out of this joint effort to promote the adoption of an open industry standard for the authenticity and provenance of content circulating on the internet and social networks.”

Ana Maria Saavedra, director of ColombiaCheck, said that the fact that the leading fact-checking organizations in Latin America have joined the CAI gave them confidence to join as members. Although so far they have not started implementing the technological protocol, in the coming months they will hold meetings to discuss the steps to follow for the implementation of the initiative.

"We believe it’s a project that can contribute to the fight against disinformation," Saavedra said. "It's not a very big commitment because it's not that we've signed a document in which we commit to do something that we're not sure about or that goes against our guidelines. Rather, it's something that seeks to support us to be able to identify disinformation."

Verification organizations tend to focus on the most viral or far-reaching material, Lüdtke said. And content credentials would help prevent manipulated pieces from reaching that virality and misinforming the public. Comprova's editor-in-chief said he hopes CAI's digital content authenticity and provenance tools will serve to prepare his teams for when they face verifying deepfakes.

Both Lüdtke and Saavedra agreed that these tools will work in a complementary way with the journalistic verification techniques used by fact-checkers, such as reverse image search and detail analysis.

"We have a step-by-step for verification of deepfakes, modified images, or images made with artificial intelligence," Saavedra said. “To do fact-checking journalism of the photo’s context, the photo’s truthfulness, all the elements one has to analyze as well during a check.”

For Adrián Pino, coordinator for the Argentine fact-checking organization Proyecto Desconfío, which offers fact-checking training to journalists in the region, CAI is an opportunity to explore standards that could accelerate the process of verifying suspicious content.

"The more signals we can generate to distinguish authentic content from fake, manipulated or misleading content, the more opportunities we have to bring trustworthy content to citizens," Pino told LJR. "The more agencies and news outlets adopt this standard, the faster the fact-checking work will be."

Reichertz said that CAI is not being presented as an ultimate solution to disinformation regarding digital content and agreed that it’s not coming to replace the work of journalists.

"There are few concrete solutions [to disinformation], and while this [the CAI], being concrete, is not complete. It is additional support to combat disinformation, but it’s not the solution," he said. "Fact-checkers know this very well. They know very well the challenges they're going to face with artificial intelligence and they know very well that they won't be able to get to everything."

Banner: Illustrations generated by artificial intelligence through Bing Image Creator