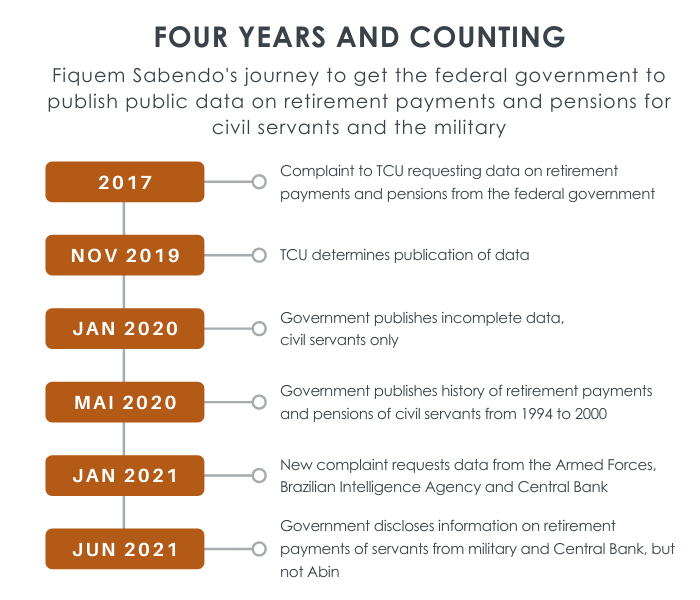

Seventy stories and still counting. This is the main result of an ongoing struggle waged since 2017 for the disclosure of all pension and retirement payments by the Brazilian government. On the front line is Fiquem Sabendo, a journalism agency specializing in the Freedom of Information Act (LAI, for its acronym in Portuguese).

“Our main objective is to show that the LAI can be used in daily journalism. LAI takes time. To work with LAI, you have to make hundreds of constant requests and stay on top of it,” Maria Vitória Ramos, co-founder and director of Ficam Sabendo, told LatAm Journalism Review (LJR).

Brazil’s Freedom of Information Act came into force in 2011, sanctioned by then-president Dilma Rousseff, to regulate an article of the 1988 constitution that ensures the right of access to information from the federal government and the federative units. This includes the breakdown of salaries, retirement payments and pensions paid by the government. However, although the salaries of active public servants were available on the Transparency Portal, this was not the case for inactive ones.

“The case of [retirees and] pensioners began in 2017 with the first complaint we made to the TCU* [Court of Audit of the Union] showing that it was not known who was receiving pensions, how much the government was spending. It was a totally obscure area,” Ramos recalled.

In September 2019, a decision by the TCU forced the government to disclose the data, which was done two months later. Fiquem Sabendo announced the feat in the January 2020 Don’t LAI to Me newsletter, but soon after, a number of corrections needed to be made.

Maria Vitória Ramos, co-founder of Fiquem Sabendo: Pensions and retirement payments were a totally obscure area. Photo: Courtesy

“There is no flawless victory. The government had said that they were all federal government pensions. And then when our first newsletter went out, we started receiving DMs on Twitter, 'look, I looked and I couldn't find my relative who receives a pension.’ And then we found out that the government had not published the entire federal government,” Ramos said.

Although the government announced that the data covered all pensions, they were incomplete: those referring to servants of the Brazilian Information Agency (Abin), the Central Bank (BC) and the Armed Forces were missing.

Even so, the Brazilian press was already taking advantage of this first wave of data to make several reports that, for the first time, shed light on information that should have been public for a long time. Thus, piauí magazine showed, for example, that the heirs of an auditor from the Federal Revenue received some type of pension for 107 years. He died in 1912 (at the time, the position was called customs treasurer), the last pension paid to his descendants had been made in 2019.

The government also had not published the entire history of payments to civil servants, disclosing only the most recent ones. In other words, the fight was on two fronts: for historical information and for data from Abin, BC and the Armed Forces.

New requests via LAI followed until, in May 2020, the history of payments to retired civil servants and pensioners since 1994 was made available online, in one of the largest databases ever obtained through LAI in Brazil.

“There were 27 files, with over 100 million lines of data. The total was 60 gigabytes in CSV format. We couldn't open the file [in common software, such as Excel],” Ramos said.

Fiquem Sabendo called in two data science experts to clean up the data and create a searchable visualization for lay people, such as journalists.

Fernando Barbalho: Processing, identifying errors, preparing visualizations out of 60 gigabytes of data, with more than 100 million lines. Photo: Courtesy

“It was a very large database. 1994-2020, 27 years of data. I had to process it, identify errors, prepare visualizations. The data was difficult to work with. We found several anomalies in these data,” Fernando Barbalho, one of the data scientists who accepted the mission, told LJR.

It fell to fellow data scientist Álvaro Justen to transform the inaccessible mess of separate files into a dynamic and easily accessible online tool for reporters, researchers and citizens. As a result, it was possible to identify a series of failures that ultimately contributed to the government improving and updating its own data.

In the accounts of Fiquem Sabendo, the detected anomalies amounted to BRL 4.9 billion, or the equivalent of USD $945 million.

“We made spreadsheets with payments above BRL 100,000. We looked at each of the payments. In 15 more serious cases, HR [human resources] had entered the wrong data. And the bulk of what we identified as error was data extraction [by the government system itself],” Ramos said.

According to the director of Fiquem Sabendo, the identified flaws were relayed to the government and later corrected in the database: "we found a technical sector interested in knowing what was happening."

“When civil society takes possession of these data, one of the gains for the government is the improvement in the quality of the data. There is a possibility of better evidence for public policies, gaining legitimacy, decreasing information asymmetry,” said Barbalho, who is also a researcher in the area of transparency and public data.

Parallel to data processing, Fiquem Sabendo coordinated a collaborative task force with four journalists to produce reports using the database.

“We knew that we as Fiquem Sabendo did not have the arms to report on this data. We are focused on LAI,” Ramos said.

Lucio Vaz: Data used in 15 reports on public servants' retirement payments Photo: Courtesy

One of the collaborators was reporter Lúcio Vaz, from Gazeta do Povo.

“I have been reporting on civil and military pensions, mainly military, continuously for four years, but I had been having difficulties. I was able to advance a little [by myself], but it wasn't enough,” Vaz told LJR.

In successive requests via LAI, Vaz had been able to find out the total value of military retirement payments and pensions and some demographic data, such as age groups, but the Ministry of Defense refused the requests for details, such as names, individual values, etc.

“Fiquem Sabendo had this super important role [in the release of the data]. They have legal support that I don't have,” said Vaz, who has already written 15 stories based on the data released. One shows that the oldest pension is for the single daughter of a federal employee. The pension marked 100 years in 2021.

In the most recent victory, the government released data on military and Central Bank pensioners at the beginning of July. This time, the data was added to the Transparency Portal in a way that any common user can search. Information about Abin, however, is still kept confidential.

Bruno Fonseca: Pensions for heirs of soldiers accused of crimes under the dictatorship. Photo: Courtesy

Reporter Bruno Fonseca, from Agência Pública, used data on pensions and retirement payments from the Armed Forces to show that heirs of soldiers accused of crimes in the dictatorship receive BRL 1.2 million a month from the Brazilian government.

"The reports were only made possible by the judicial victories obtained by Fiquem Sabendo against the federal government's refusal to disclose the databases," Fonseca told LJR. “I already had a request for information denied, as well as other journalists. Even today, the database would not be known by the public were it not for the legal victory of Fiquem Sabendo.”

With a team of ten people, of which only one works full time, Fiquem Sabendo has an annual budget of BRL 288,000 for 2021 (USD $55,000). The agency makes and monitors between 2,000 and 3,000 requests via LAI per year to the federal government, other powers and federative units.

LJR contacted the Office of the Comptroller General, the agency responsible for transparency in the federal government, but the request for an interview was not granted.

*Translator's note: TCU is the Brazilian federal accountability office.