Digital violence against journalists is a growing phenomenon in Latin America. In response, a group of journalists from Brazil and Mexico turned to artificial intelligence to explore the source of violent narratives against journalists in the digital world.

The Brazilian Association of Investigative Journalism (Abraji) and Mexican data journalism nonprofit Data Crítica joined forces to develop "Attack Detector," a tool that combines data journalism and machine learning to detect hate speech online.

In Brazil alone, the environment of digital violence against journalists has increased compared to previous years. In its most recent Monitoring of Attacks on Journalists in Brazil, published this March 29, Abraji revealed that throughout 2022 more than 550 aggressions against journalists and media outlets had been recorded.

The report "Monitoring of Attacks on Journalists

in Brazil 2022", published on March 29 by Abraji, revealed that in 2022 more than 550 aggressions against journalists and media outlets were recorded. (Photo: Abraji)

Of this total, 61.2 percent corresponds to episodes of verbal violence or stigmatizing speech, with 341 registered cases. And of those, 298 cases (87.4 percent) originated online, mainly on social media.

In this context, "Attack Detector," a natural language processing (NLP) model, was created to detect attacks via Twitter, not only against journalists, but also against environmental activists and land defenders in Brazil and Mexico.

The tool was developed by Fernanda Aguirre, Gibrán Mena (from Data Crítica), Schirlei Alves and Reinaldo Chavez (from Abraji) as part of their participation in the first generation of the JournalismAI Fellowship, an initiative of JournalismAI, the London School of Economics and Political Science (LSE)-based organization on journalism and artificial intelligence. The program gathered 46 journalists and technical media professionals from 16 countries in 2022 to develop projects that explore a responsible application of artificial intelligence in journalism.

"In Brazil we have this problem that is not over, where [there is] hate speech on social media against various types of people involved in political issues, not only journalists, also women in various positions of power or people from minorities and people who defend the environment," Chaves, Abraji's project coordinator, told LatAm Journalism Review (LJR). "We thought: 'Why not use machine learning techniques to begin to understand this better?' And together with Data Crítica we made a project that is still in a Beta phase. There are many things which could be done this year, but we can already investigate in an automated way in a social media platform -Twitter- these kinds of speech against journalists and environmental activists."

The team took as a precursor the Political Misogynist Discourse Monitor, a tool for detecting hate speech against women developed in 2021 by Data Crítica, Revista AzMina, La Nación, and CLIP, as part of the Collab Challenge, a previous initiative by the JournalismAI Fellowship. This Monitor worked by training a PLN model with dictionaries of misogynistic terms the model had “learned.”

"Attack Detector, on the other hand, is based on open source multilingual models, such as RoBERTa, a PLN model for sentiment analysis (also called opinion mining) that identifies the emotional tone behind certain text, among others.

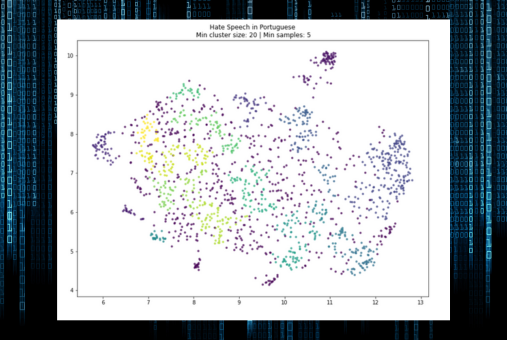

"We use sentiment analysis to check the similarity or proximity of words to understand whether they reflect the same sentiment. In our case, we look for hate. With this we can 'cluster,' separate large blocks of posts," Chaves said. “In our case, we use this clustering for that, to have those degrees of hate possibilities.”

Before training PLN's models, the team conducted research on which journalists' and activists' profiles were most attacked on social media, the words most used in such attacks and the most frequent types of perpetrators, among other criteria. To do so, they interviewed experts and organizations that closely follow online violence against members of the press, such as Article 19, in the case of Mexico.

By tracking those profiles, they selected a sample of tweets directed at frequently attacked journalists and activists and manually labeled those that met the characteristics of hate speech attacks. With that information they trained PLN models, automating the analysis and then optimizing it.

With the data obtained through the model and metadata such as user data, date, time, and geographic location of the tweets, it is possible to make analyses of, for example, how the flow of dissemination of these attacks arises, the interaction between users and tweets, and whether there are already established communities for the creation and dissemination of such attacks.

"We can also know at what times of the day [attacks] usually happen. Because if we can identify that, maybe later we can link it to the context of what's going on in the country. So, maybe if a certain political event or some incident happened, we can know what could be triggering that attack," said Aguirre, who was also part of the team that developed the "Misogynist Political Discourse Monitor."

The development of "Attack Detector" began in June 2022 and took about six months. It was not until November of that year that the model entered a pilot stage, in which it was launched to monitor selected Twitter accounts.

From then until now, the team is still working on optimizing the tool's operation. It aims to adjust it so that it is increasingly capable of identifying not only attacks with specific offensive words, but also attacks with less literal expressions, such as those that include irony, veiled insults or attacks that are not so straightforward.

"You also have to deal with phrases that look like attacks, but they contain irony. There is no computer that can manage to detect with certainty whether it’s irony or whether it’s a hate speech attack. This can only [be done] by a human being who understands, for example, the reality of Mexico or Brazil," Chaves said. "Today we can detect these cases of irony, but they are classified as attacks. For them to be classified as ironic, we have to improve our training database, which is one of this year's priorities and goals."

Fernanda Aguirre and Gibrán Mena, from Data Crítica (Mexico); and Reinaldo Chaves and Schirlei Alves, from Abraji (Brazil) formed the team that developed "Attack Detector". (Photo: JournalismAI)

The "Attack Detector" team hosted all the information related to the model in a GitHub. They will also enable a website where the public can download the tool’s databases and see a series of data visualizations created with the monitoring results. Some of these visualizations will include the Twitter users with the highest number of attacks, the users who initiate the most attacks, and the most attacked journalists and activists, both in Mexico and Brazil.

Although the JournalismAI Fellowship program ended last December, Abraji and Data Crítica plan to continue working together on the Attack Detector training, using resources from both organizations. The next step, they said, is the development of an API (application programming interface) so that other organizations can make use of the model to monitor online hate speech in other areas. The team expects the API to be ready later this year.

"We want to leave the door open for other organizations to use it through the API," Aguirre said. "For example, in an election period in Mexico, if there is any organization that monitors political violence, as the model detects sexist language, it can be applied to many other things, such as monitoring female candidates for those elections or women land defenders, exclusively. I think its use can be quite broad and can be adapted to different types of investigations."

The use of artificial intelligence in journalism is always accompanied by ethical dilemmas, and PLN tools are no exception. Aware of this, the Attack Detector team members made sure that their model had some level of human supervision at all times.

During its training to detect hate speech, the tool was constantly audited to evaluate how well it was doing its job by manually verifying its results.

"It's not a process that is entirely automated, because there is always human presence to a greater or lesser degree, even if it's simply to check and say that the labeling was correct. But we don't let it be something that can only be decided by the algorithm," Aguirre explained.

When the model encounters text in which hate speech is not so obvious or when it is veiled, the team intervenes to make a second assessment. According to the developers of Attack Detector, PLN models do not always follow a defined pattern, and their results do not take into account contextual factors.

"Attack Detector is based on open source multilingual models for sentiment analysis, which identify the emotional tone behind certain text. (Photo: Attack Detector)

"It's hard to sort [hate speech] just through a robot and not have the human part there to really understand what's going on in a barrage of attacks," Alves, a data journalist specializing in human rights and the other Abraji representative on the team, told LJR. "It helps in this effort to [handle] a large volume of information, but you also need to have someone there to make the final adjustment, so to speak. You always have to have that human eye to be able to do the final sorting of seeing what really is and what really isn't [a hate speech attack]."

Like the social phenomena they analyze, computer models such as "Attack Detector" evolve and change over time, and therefore must undergo constant maintenance and updating of the databases they run on. Abraji and Data Crítica representatives plan to continue testing new PLN and linguistic analysis models to improve the accuracy and performance of the tool.

The team hopes in the near future to partner with other organizations that defend freedom of expression, both in Brazil and Mexico as well as in other countries. The model can have a practical application in the understanding of digital violence against journalists and its combat. It can also expand the capacity of "Attack Detector" to perform not only with content from Twitter, but also in other platforms where there’s hate speech violence, such as Facebook, Instagram and TikTok.

"We have noticed that there is digital violence, unfortunately and quite frequently against journalists and environmental defenders on Facebook," Data Crítica co-founder Mena told LJR. "We are looking for broad partnerships and funding to expand efforts. First in developing analysis on other platforms, such as Facebook, and then in creating impact strategies where we can make a tool like this have a clear impact on decreasing digital violence against journalists."

The second edition of the JournalismAI Fellowship will be held this year and registration is now open for those who wish to develop new projects that link the use of artificial intelligence with journalism.

JournalismAI invites journalists and media technical professionals from around the world to participate in the program, which is free of charge and conducted entirely online.

“Unlike other fellowships, the JournalismAI Fellowship Programme will not select individual fellows. Instead, up to 15 pairs of Fellows will be selected to join the 2023 cohort. They will form teams that will work together over six months towards building AI-powered solutions that enhance reporting,” Lakshmi Sivadas, project manager, told LJR.

The JournalismAI Fellowship will run from June to December 2023. Those selected will be required to spend at least eight hours per week on the development of their projects. Each team will receive financial support, as well as mentoring and training from experts in the use of artificial intelligence in journalism.

The deadline for applications is April 21.