Mexican journalist Juan Alberto Vázquez was covering the trial of drug trafficker Joaquín "El Chapo" Guzmán in January 2019 in a federal court in Brooklyn, New York, when he found out that a group of Mexicans accused of human trafficking would be sentenced in that same court.

Vázquez decided to attend the hearing and was surprised by the case. Five men from the municipality of San Miguel Tenancingo, in the Mexican state of Tlaxcala, who were part of a criminal human trafficking group had pleaded guilty to racketeering, sex trafficking and other federal charges. Although he was already aware of the existence of Mexican trafficking networks operating in the United States, Vázquez was unaware of the size and scope of criminal groups from Mexico's second-smallest state.

The journalist became interested in the subject and investigated thoroughly. Through court documents and hearing transcripts, he learned the gruesome details of how these sex trafficking rings operate. He found that entire families run million-dollar trafficking businesses from San Miguel Tenancingo, that this small Mexican town is one of the epicenters of human trafficking in the world, and that these groups operate with total impunity and allegedly in complicity with authorities.

But what surprised him the most was that few of these stories reach the press and society in Mexico.

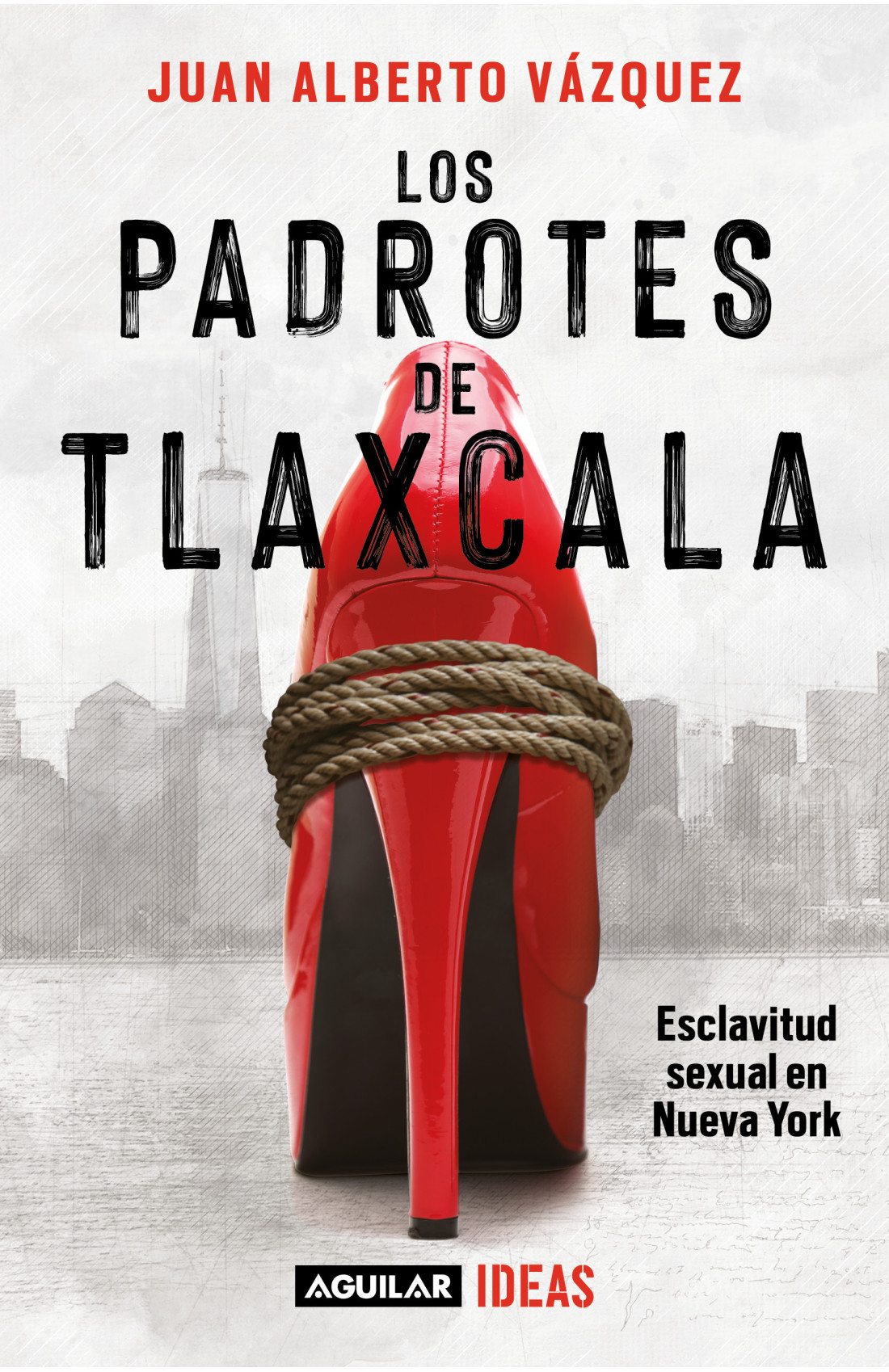

"Los Padrotes de Tlaxcala" (The Pimps of Tlaxcala) was released this year under the Aguilar brand of Penguin Random House Mexico. (Photo: Courtesy Juan Alberto Vázquez)

“I realized that there was not much information about what was happening here in the courts in the United States: when they are detained, the testimonies of the victims, how the processes are carried out... In other words, the judicial part [...] was something that was unknown to public opinion in Mexico,” Vázquez told LatAm Journalism Review (LJR).

The journalist discovered that the U.S. judicial system offered possibilities for finding information on cases of Mexican criminals tried in U.S. courts, which few journalists know they can access from Mexico. He undertook the task of conducting an in-depth investigation of sex trafficking in New York to reveal a complete picture of the problem, beyond the press releases that are picked up by the Mexican media. And he did it precisely through the legal proceedings.

The result was the book "Los Padrotes de Tlaxcala” (The Pimps of Tlaxcala), published in June of this year and which addresses the phenomenon from the stories of five groups of people accused of pimping who had been tried in New York. According to Vázquez, the objective of the book is not only for his compatriots to know the magnitude of the problem of human trafficking, but also to open the way for a discussion on how to combat it.

“Pretty much what I got myself into is trying to give an explanation, a big, real picture of a problem that is still going on,” he said. "Right now there are Mexicans who are being prosecuted, there are women who are being abducted and taken for this crime, so it is a very current problem."

Colleagues in Mexico believe that Vázquez's investigation focused on a part of human trafficking legal proceedings – what happens between the arrest of the accused and the issuance of their sentences — that had always remained off the radar of most of the Mexican media.

"The issue had never been addressed from the perspective of the sentences, which for me is an important element that media in the state [of Tlaxcala] do not have due to the economic difficulties of doing broader coverage," Fabián Robles, journalist and media manager from Tlaxcala, told LJR. “I speak of an important contribution, for revealing details of that part that occurs in the courtrooms of New York, which we miss here. [...] That is why for me it is the missing link, because we do not have that information here.”

Before delving into the subject of human trafficking, Vázquez had already covered high-profile court cases in New York courts. Since he settled in that city in 2017, he has reported for Mexican and U.S. media on trials such as that of the founder of the NXIVM cult Keith Raniere, and that of former Mexican Secretary of Public Security Genaro García Luna, as well as that of "El Chapo" Guzmán.

Vázquez has found in legal proceedings an important source of information on cases that are relevant to audiences in both Mexico and the United States, as well as a way to keep track of sources that would otherwise be very difficult to cover.

“The judicial part is something that I have seen that in Mexico does have a lot of relevance or a lot of interest from the people. Articles about arrested drug traffickers, all of that is very attractive to the reader there in Mexico and that's what I've been doing,” he said.

Unlike what happens in Mexico, where obtaining documents from judicial systems can become a bureaucratic mess, in the United States there are ways of accessing court cases relatively easily.

In that country, there are electronic repositories of legal case documents that anyone can access. One of the best known is PACER (Public Access to Court Electronic Records), created by the Administrative Office of the United States Courts. The platform offers electronic access to details of the cases, including data on the defendants, judges, lawyers and witnesses, case status, trial chronology and hearing transcripts.

The platform has been criticized by media such as The New York Times for requiring payment for access to information that is public. PACER charges users a fee of US $0.10 per page, with a maximum fee of $3 per document, according to its website. Searches also carry a cost, based on the number of pages generated from each search. Audio files of some hearings are available for US $2.40 per file.

However, for Vázquez, the platform is of great help to shed light on court cases of international relevance, even for journalists who follow the cases from other countries.

“[PACER] charges you very little, although if you're someone who works these cases on a permanent basis, obviously sometimes the bills are as high as $100 or $200,” he said. “But obviously what you find there is wonderful, it's gold, because there you find transcripts of hearings in which you were not present, some presentations of some evidence, photographs [...], everything that the prosecutors or the defense put in. There is a good amount of information there that is very useful for reporting purposes.”

According to the journalist, the fact that Mexican criminals and officials are tried in the United States and not in their country of origin opens a window of opportunity for journalists, as long as they learn to use systems like PACER and know how to approach the sources.

Vázquez's book addresses the phenomenon of women trafficking through the stories of five groups of Mexican pimps who have been tried in New York. (Photo: Courtesy of Juan Alberto Vázquez)

Although in Mexico there is the Federal Law on Transparency and Access to Public Information, there are also multiple bureaucratic obstacles that make the delivery of information to journalists and citizens difficult, especially when it comes from law enforcement institutions.

“To get a document there [in Mexico] is torture, really, it's a nightmare. There is supposed to be a system in the country – more than 10 years old – in which you can ask for the documents and they have to give them to you, but now there are a lot of problems,” Vázquez said. “And then that can take you months and months of litigation and suits, of asking for a document that you can get here in half an hour. It is the difference between investigating there and investigating here”.

Another advantage of investigating in U.S. courts is the availability of prosecutors to deal with journalists, Vázquez said. Although they are generally reliable sources, it must be taken into account that their views are biased and that even prosecutors sometimes try to use their interactions with the press to strengthen their cases, he said.

“Here in the United States it looks very bad for a prosecutor to lose a case. So they do everything possible to prevent that from happening. It generates a lot of discredit for them and then they do have tricks that are not entirely ethical, or legal, or correct,” he said. "Obviously, as a journalist, knowing that, you have to be careful when you have a judicial source that is telling you something."

Vázquez hopes that "Los Padrotes de Tlaxcala" will raise awareness about the exploitation of people for sexual purposes, an activity that the UN considers a form of modern slavery, along with other illegal activities such as child labor, forced marriage and the use of children in armed conflicts.

To achieve this objective of raising awareness on the issue, the author sought to give victims a voice and push from journalism so that States care about the affected women and girls, and help them regain a purpose in life.

“As journalists, we do have to concentrate and focus on denouncing, on exposing what sexual slavery is,” he said. “We have to be relentless in denouncing, publicizing and obviously investigating trafficking networks, when women are enslaved. Also try to give the victims a voice, try to put pressure so that the victims get attention.”

Accessing victims of human trafficking is not easy and requires a lot of sensitivity, Vázquez said. For his investigation, he was lucky that a woman who had suffered sexual exploitation contacted him on social networks in January 2022, after he published an article about the sentence of a group of pimps.

To reach other victims, the journalist approached organizations that help people who suffer sexual exploitation. One of them was the Comisión Unidos Vs. Trata, chaired by Mexican activist Rosi Orozco, who has fought for more than 20 years to combat human trafficking and who was interviewed by Vázquez for his investigation.

The journalist recommends collaborating with organizations and activists to learn the stories of the victims first-hand. Although there are women who do not agree to speak because they are still in a state of trauma, there are others who want to share their story and just need the journalist to inspire them with confidence.

"The NGOs have more relationships with victims because they are helping them, so when they realize that it is a serious job or that this approach that you are looking for has the seriousness and journalistic rigor, they normally talk to them," he said. “I also reached out to other people who are even mentioned in my book, who did not want to give me an interview because they are not ready yet.”

For his book, Vázquez was also able to talk with some pimps from Tlaxcala who are in jail, thanks to the fact that the U.S. justice system also offers this possibility. The United States Federal Bureau of Prisons maintains a website with a database where inmates of federal prisons can be located. The site also indicates ways to contact them, mainly through letters, or through their lawyers. The same is true of most state prisons.

“I sent letters to most of the Mexicans who are imprisoned here [for human trafficking]. I explained to them that I was a journalist and that I would very much like to talk to them, I gave them my phone number and that's it, that's how most of them responded to me," Vázquez said. "They dialed my phone and in these calls I was able to have access to them."

In these calls from prison, which are limited to 15 minutes, the journalist said that he allowed the people he interviewed to express themselves freely, instead of asking them specific questions, since in such a limited time there is no opportunity to create an environment of trust for questions.

“What I was trying to do was get them to vent a bit, to tell me what they wanted, without trying to intimidate them or accuse them again. Just trying to make it more relaxed and for them to express themselves and for part of what they think and believe to come out there,” he said.

There is also the possibility of visiting inmates, either through the prisons themselves or through lawyers. However, this is a bureaucratic process that involves more requirements and can take several months. Vázquez said that he was about to visit a couple of defendants in a Pennsylvania prison, but the process got stuck.

“But if you can, you can. If you push and if you try, you can go to jail as a journalist and you can interview an inmate,” he said. “These are resources that the United States judicial system offers you so that you can tell a story.”

Vázquez traveled to Mexico between July and August of this year as part of the promotion of his book. One of the stops on the tour was in Tlaxcala, where on Aug. 10 the author presented his book in the Congress of that state.

There he found out, however, that "Los Padrotes de Tlaxcala" was impossible to find in the Educal and Fondo de Cultura Económica bookstores, which belong to the Federal Government's Ministry of Culture, and that the only way to get it was by order in small private bookstores or through online stores.

The journalist does not rule out that this is due to an attempt at censorship by the state government, whose governor, Lorena Cuéllar, has insisted that human trafficking no longer exists in the state.

Some local reporters in Tlaxcala said they were instructed not to cover the presentation of Vázquez's book in the state's Congress, according to journalist Fabián Robles. (Photo: Screenshot from Facebook Live)

"What is happening right now with my book is that it is being obtained clandestinely [...], they have not put it on shelves, surely because they have received some kind of warning," Vázquez said.

Suspicion grew when no legislator from the governor's party attended the presentation of the book in the local Congress and when a woman discredited the book and other investigations that journalists and academics have carried out on human trafficking in Tlaxcala. Robles, who was one of the organizers of the presentation, interpreted it as an attempt to boycott the event. In addition, some local media said they had received instructions not to cover the event.

“I invited some colleagues from the media to cover [the presentation] [...], although some came, others did not. Some, because of the trust they have in me, told me that they definitely had instructions from the state government not to publish a single line about that event. So, once again we are facing an act of prior censorship," Robles said.

A source from the Penguin Random House Mexico publishing house, to which "Los Padrotes de Tlaxcala" belongs, confirmed to LJR that the book is not being distributed in government bookstores in Tlaxcala due to a debt that they have been carrying since previous administrations, so none of the publisher's recent releases are available in those bookstores.

The governor’s office of Tlaxcala did not respond for a request for comment as to whether Vázquez’s book is being censored by it.