When, in 2018, Mexican journalist Alejandra Ibarra began build the Defensores de la Democracia [Defenders of Democracy] project, which seeks to preserve and catalog work published by journalists murdered in her country, one of her main concerns was to understand why Mexico was such a violent nation for the press, despite being a democracy with all the protections of the law.

Ibarra and her Defenders of Democracy team thought that in the work of murdered journalists they could find clues to understand the reason for such violence, which between 2000 and 2023 had claimed the lives of at least 162 journalists, according to Article 19.

The journalist said that at first, when reviewing the work of her murdered colleagues, she expected to find aggressive journalism, with hard-hitting revelations or sensitive topics. However, she came across journalism that appeared to be the most harmless and about the everyday.

For her book, Ibarra investigated what the journalists murdered in Mexico have in common, their work, and the historical moment in which they were killed. (Photo: Courtesy)

"I was expecting to find highly sophisticated investigations, of lurid subjects, of organized crime, that would have found quite sensitive evidence," Ibarra told LatAm Journalism Review (LJR). "Quite the opposite. What I found is everyday, community-based journalism. And that prompted the first big question: Why is it that this journalism that seems so harmless in a certain sense is the one that causes colleagues to be murdered?"

From the research and compilation of Defenders of Democracy, and dozens of interviews for the podcast that stemmed from the project, "Voces Silenciadas [Silenced voices]," Ibarra began trying to find patterns and figure out what the murdered journalists have in common, their work and the moment in which their lives were snuffed out. The findings of that research were presented in the book “Cause of death: Questioning power. Harassment and murder of journalists in Mexico.”

In the book, Ibarra argues that it is not so much the information journalists disseminate, but the role they play in their community that leads them to be targeted for assassination. One of the patterns that the journalist found is that the journalists killed in recent years in Mexico were mainly local reporters or citizen journalists who held a place of respect in their community. They were able to promote some social participation when they took a stand on the facts. They were also figures who often questioned the powers that be in their town.

"I argue that [their journalism] arises from them being members of the communities they cover. In their journalism, they take a stand. That is, they don't just say 'this hospital lacks medicine,' they say 'this hospital lacks medicine and that’s unfair,'" Ibarra said. "This taking a stand comes from the role they have as social leaders. They invite other people to also take a stand, raise their voices, be nonconformist, and participate in issues."

Another pattern she found is that the murdered journalists in the cases she analyzed had a lot of editorial freedom and were founders of their own news outlets, from Facebook pages to print media, or worked in community media.

When the above two factors come together at a time when local power, official or de facto, is going through moments of instability — such as electoral campaigns or territorial dispute among several drug cartels — the likelihood of lethal violence against journalists who take a stand and raise their voices increases, Ibarra argued in her book.

"These homicides are not a means to an end. That is, they don't kill the journalist to hide certain information, but rather homicides are an end in themselves," she said. "They kill to punish them, they kill to say 'this is what happens when you dare question me.'"

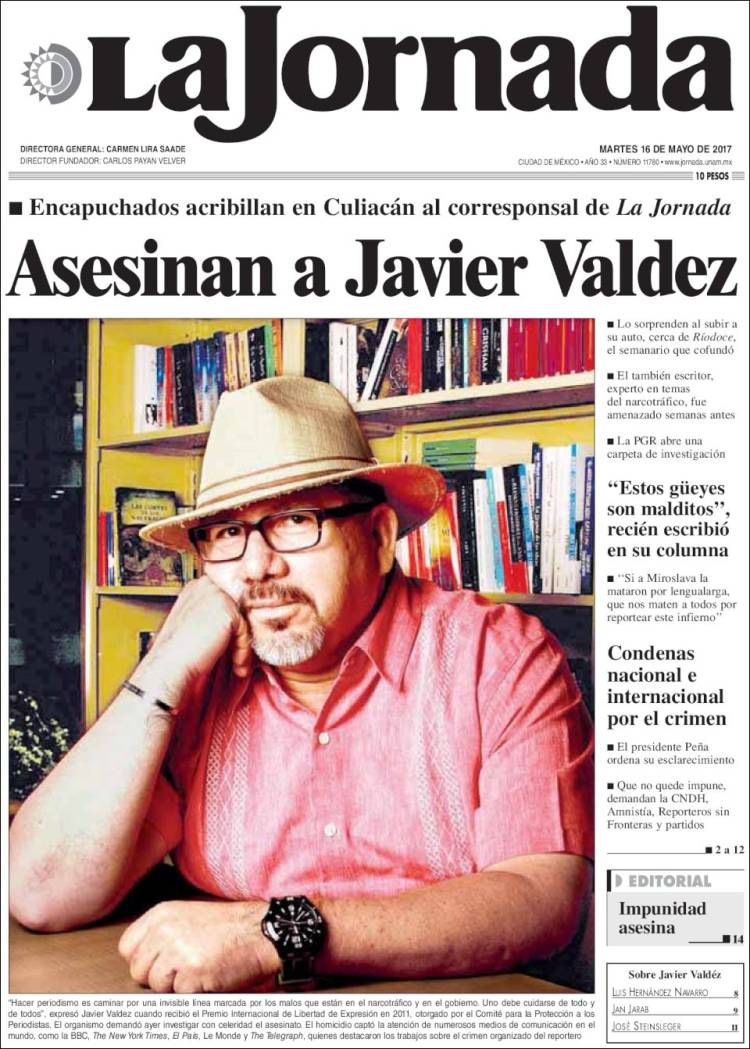

The cases analyzed in "Cause of death: Questioning power” are those of Javier Valdez, founder of the weekly Ríodoce who was murdered in 2017 in Culiacán, Sinaloa; Nevith Condés, founder of the news outlet El Observatorio del Sur who was murdered in 2019 in the State of Mexico; Samir Flores, founder of the community radio station Radio Amiltzinko who was also murdered in 2019; and Juan Antonio Salgado, a police officer in the state of Baja California Sur who denounced in social media wrongdoing by his superiors and who was murdered in 2014.

The case of Salgado and that of Felicitas Martínez and Teresa Bautista, these last two also mentioned in the book, are, for the author, examples that illustrate the disagreement that exists between authorities and organizations defending freedom of expression about who should be considered a journalist and who should not when classifying a murder. Martínez and Bautista were members of an Indigenous community who founded the community radio station La Voz que Rompe el Silencio, in the state of Oaxaca, and were murdered in 2016. Salgado was a policeman, but is considered by Ibarra to be a person exercising journalistic activities.

According to Ibarra, such disagreement contributes to pave the way for impunity, when prosecutors rule out journalism as the cause for the attacks when the victims are not qualified journalists or were not practicing the profession at the time they were killed.

"These are local, hyper-local, community, and citizen journalists. Often, their journalism is not their main source of income. They drive a cab, which is what they live off, or a taquería, or an Internet café," she said. “I personally stick to the more liberal or more progressive definition, which is that anyone who is documenting what is happening in real life, corroborates it, and publishes it to inform others, is a journalist.”

Ibarra said that prosecutors often believe that the murder of a journalist only has to do with journalism when there is an element of censorship, to prevent certain information from getting out, which is not always the case. In her book, she maintains that censorship is not required for the motive to be journalism.

Although he was not a journalist, police officer Juan Antonio Salgado used social media to denounce injustices, which is a journalistic activity, according to Ibarra. (Photo: YouTube Screenshot)

"I think the very role of raising their voice, of asking, of denouncing, of demanding, that many of these journalists do, that to me is also journalistic work," she said. “They have a credible voice and a leadership voice in society. And they would not have that voice of credibility and that leadership if it were not for their journalism.”

Ibarra referred to the almost total impunity that prevails in the murders of journalists. This, she said, is simply a reflection of the impunity that exists in general throughout the Mexican justice system. In some of the cases, the perpetrators are found, but almost never the masterminds.

Ibarra found that, in the cases in which the intellectual authors have been found, they have turned out to be people who hold a certain level of power at the local level, whether political or from criminal groups.

For example, according to the investigations of Mexico’s Special Prosecutor's Office for the Attention of Crimes Committed against Freedom of Expression (FEADLE), the alleged intellectual author of the murder of Javier Valdez was a drug lord, son of a collaborator of Joaquín "El Chapo" Guzmán. In the case of the murder of journalist Moisés Sánchez in 2015 in the state of Veracruz, the alleged mastermind was the then-mayor of the municipality Medellín de Bravo, according to authorities.

"One way of looking at it is very much in the Latin American tradition, if we think of caciques, or caudillos or local strongmen. Historically in Mexico, political caciques were a bit combined with organized crime and I think that's what still happens," Ibarra said. "I think of them, not as two different spheres, but as people who hold power in a community for whatever reason. But the way in which they hold power is very similar."

While mainstream journalism tradition states that reporters should be impartial and avoid taking a position on the facts, this does not exactly apply when it comes to citizen or community journalists, according to Ibarra.

Throughout her research, she found that it is easier for a journalist to be neutral and objective when the political system around them is not in question, or when it does not directly affect them. This is not the case for journalists who are killed in Mexico, according to her book.

"There are a lot of male, cisgender, white journalists who really aren't affected by political debate. So they do have a bit of the privilege of distance, to be able to be objective. But when the political debate affects you, I find it much more complicated," Ibarra said. "If I lived in a town where young people are disappearing and I have children the age of the disappeared young people, I don't know how or why I should be objective."

Javier Valdez, murdered in 2017, founded his own media outlet, had broad editorial freedom and was respected in his community. These factors are present in other murders of journalists in Mexico. (Photo: La Jornada)

The murders of journalists are the ultimate expression of violence against the press in Mexico, but they are not the only one. In that country, officials at all levels frequently criticize journalists who question authorities. The President of the Republic himself, Andrés Manuel López Obrador, constantly verbally harasses journalists and news outlets, exposing them and accusing them of being his opponents.

For Ibarra, both regarding the murders and the verbal harassment, the motivation for attacking the press is the same.

"Those who verbally assault journalists and those who physically assault them are based on the same principle, which is to feel offended or feel that the journalist is stepping out of his or her assigned place by challenging them or questioning them," she said. “They believe it’s a kind of affront, instead of understanding it as a democratic function.”

In her opinion, the fact that critical journalism is seen in Mexico as an affront and not as a manifestation of democracy has to do with a lack of democratic education, especially on the part of public officials. And this, she said, is due to the fact that the country lived through more than seven decades of government by a hegemonic party, during which most journalism did not play a critical role, but rather reproduced the messages of the government in power.

"I think there is a tradition from the authorities and public officials, who still do not conceive of journalism as something different from that. I don't think the value of journalism is understood and there is this expectation that journalists should reproduce the message of public officials," she said. "I do think there is a lack of democratic education on the part of public officials, in that sense."