Questions from journalists can be uncomfortable and embarrassing for public officials under pressure. It’s no wonder, many press conferences carry an air of tension and it is not uncommon for those who are on the other side of the microphone to try to protect themselves, cautiously answering questions. However, it is also not uncommon to try to control who and what can be asked, or, even worse, to call press conferences without questions, where contradiction is prohibited.

“Limiting the ability for journalists to ask questions is a discourse control technique. For this reason, it is a way to avoid incisive, critical journalism that could, for example, through intelligent interrogation, reveal contradictions, paradoxes, doublespeak, incoherence, ignorance, etc. of the authorities calling the press conference,” Pedro Santander, a journalism professor and director of the Communication Observatory at Pontificia Universidad Católica de Valparaíso in Chile, told LatAm Journalism Review (LJR).

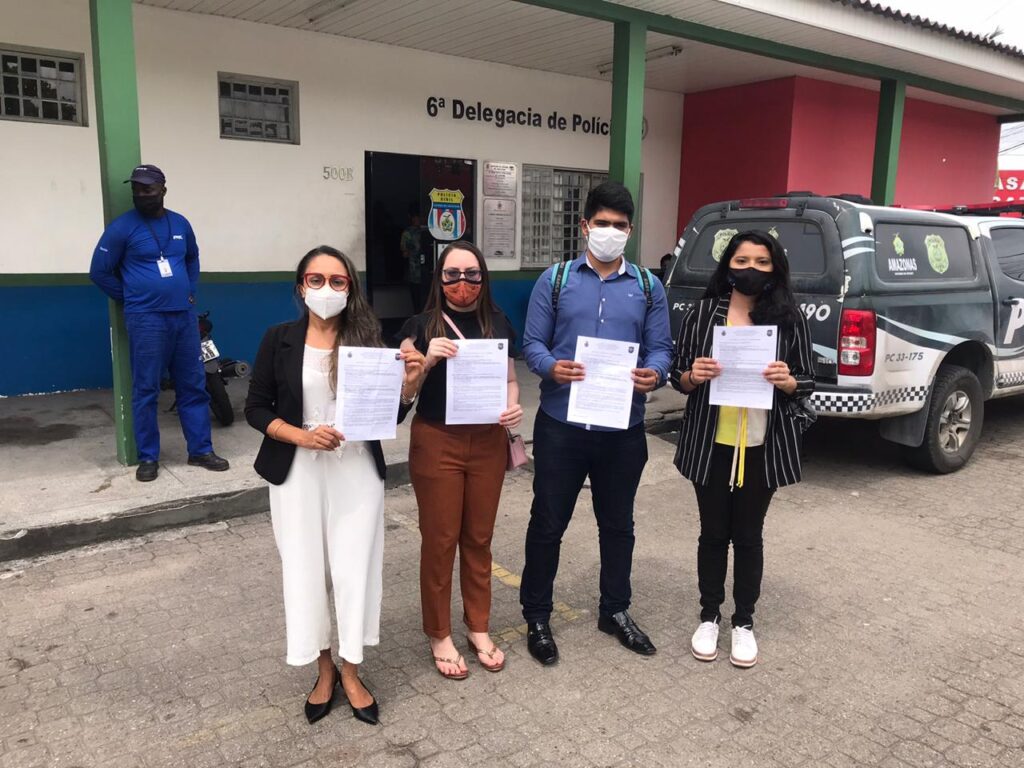

Rosiene Carvalho (in white, on the left) filed a police report on alleged assault when trying to ask a question to the deputy governor of Amazonas. Three fellow journalists showed solidarity with her. Photo: Union of Journalists of Amazonas

This tendency of some national and local political leaders in Latin America and the Caribbean gained strength with the pandemic. With social distancing rules, control over who asks questions –and when they’re asked– has increased.

In Chile, President Sebastián Piñera and his aides have adopted the practice of making statements without allowing questions from journalists starting with the social protests in late 2019. According to the “Freedom of Expression in Chile Report” of the Observatory on the Right to Communication, restriction to the press continued during the management of the COVID-19 pandemic, being replicated in regional governments, such as that of Atacama.

Indeed, the quality of Latin American democracies is increasingly in question, there is a degradation of democracies; [Jair] Bolsonaro, [Ivan] Duque, Juan Orlando, [Nayib] Bukele or [Sebastián] Piñera are paradigmatic examples in that sense,” Santander said. “Then, a correlation is established: the greater the degradation of democracies, the greater control over the discourse of the press and journalistic activity. Not allowing questions is, for this reason, a custom that occurs more and more since it reflects the low quality of democracy that is also increasing.”

In Argentina, the beginning of the pandemic was marked by the suspension of routine press conferences that took place at Casa Rosada, where officials from President Alberto Fernandéz's administration offered information and answered questions from journalists. At first, questions were banned during reports about the pandemic. Thereafter, interactions between journalists and federal officials were suspended entirely.

The Argentine Journalism Forum (Fopea, for its acronym in Spanish) suggested the government hold virtual federal press conferences to ensure necessary social distancing and the safety of those involved. But according to the organization, the proposal was not accepted.

“Despite the global experience in this regard and the virtual possibilities that the pandemic gave, these press conferences were never open to journalists from all over the country,” reads Fopea's assessment of press freedom in the country in 2020.

Also in Argentina, the government of the province of Formosa, in the north of the country, began to demand the prior and written submission of questions to be asked during interviews with local authorities about actions against the pandemic. For Fopea, what the government is doing is discarding the questions that are considered most uncomfortable.

“The journalists' questions in this context were practically the only space to be able to present the concerns of the people or to be able to question and put 'to the test' that 'official truth,’” Bárbara Read, director of the local newspaper La Mañana de Formosa, told LJR. “We understand that depriving journalists of the possibility of making themselves heard without impediment is a sneaky way of attacking freedom of expression.”

An even more serious problem occurs in Barbados, where the virtual environment in which interviews are conducted allows even more control, according to the president of the Barbados Association of Journalists and Media Workers, Emmanuel Joseph.

“You call a press conference, you’re there in Zoom and then, no questions. You’re not allowed to ask questions. Well, it’s not a press conference if you’re not allowed to ask questions. That’s one of the biggest feuds we have had in Barbados,” said Joseph, who is also a senior reporter at the newspaper Barbados Today, during a virtual event held by the Medium Institute of the Caribbean. As president of the journalists' association, Joseph is negotiating with the prime minister's office to ask questions in virtual press conferences.

In face-to-face interviews, in which journalists cannot be automatically put on ‘mute,’ failure to comply with what is determined and trying to ask questions in the scrum can cause problems for the journalist. At best, the journalist may have revoked their invitation for a future interview. At worst, the situation may escalate to physical aggression.

It happened in the state of Amazonas, in the north of Brazil. Reporter Rosiene Carvalho, from the site UOL, insisted on asking questions of the deputy governor of Amazonas at the end of his speech about alleged fraud in the purchase of respirators. He and other members of the government had been the target of an operation by the Federal Police and the case had national repercussions.

"I arrived at the moment when he was starting to read his statement, his version," Carvalho told LJR. At the end of the speech, she tried to approach the deputy governor, but was blocked and appears to have been pushed by a military police officer who was guarding him. The video of the moment of the aggression is online.

"I said I was a journalist, that I was going to ask a question, and that the deputy governor would decide whether to answer or not," she said. "The advisors were surrounding us, making a physical circle." Later, Carvalho and three other colleagues filed a police report and she posted the questions she was unable to ask on her blog.

LJR attempted to contact the deputy governor but had not received a reply as of publication time.

For the Special Rapporteur for Freedom of Expression of the Inter-American Commission on Human Rights (IACHR), Pedro Vaca, the possibility of journalists asking and counter-asking is a way of clarifying doubts on matters of public interest, the result of which is always the enrichment of the debate.

“I believe that leaders have the right not to respond. Now, the more open a leader is to that scrutiny, the more available they are to resolve doubts, on the scale of democratic credentials, they increase,” Vaca told LJR. “A closed-off leader, who does not speak, who does not expose themselves – I do not mean to say that they are authoritarian – but has less democratic credentials, is less open to debate.”