For publishing a documentary book about César Acuña, an influential Peruvian politician, journalist Christopher Acosta was sentenced for aggravated defamation and crimes against honor. The judge who led the criminal proceedings first sentenced Acosta and also the director of Penguin Random House in Peru, Jerónimo Pimentel, to two years in suspended prison terms, after ruling that various journalistic quotes in the book were defamatory.

The defense appealed the ruling and the legal process will continue if the judge accepts the appeal.

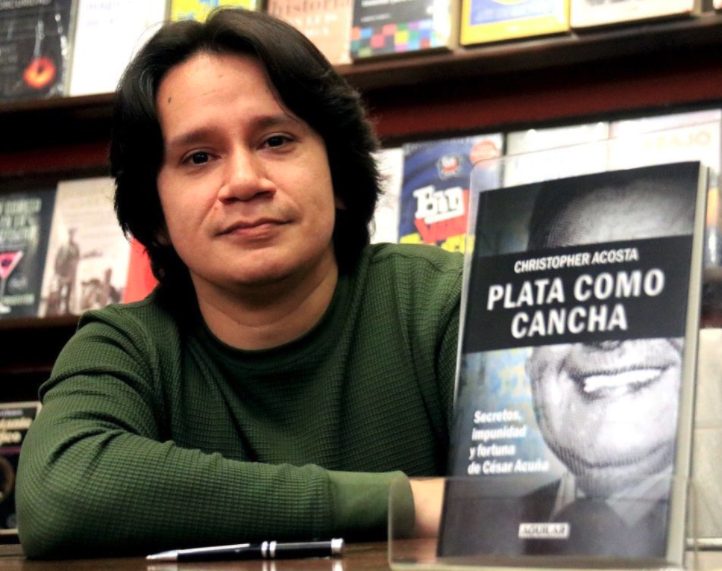

Christopher Acosta during the presentation of his book "Plata como cancha". (Foto: Paco Sanseviero via Instagram)

After reading the conviction, on Jan. 10, Acosta told the press that the judge had set "too high a bar" on journalism by considering 34 journalistic quotes from his book as defamatory. "[This] should not be a limitation for journalism."

Acosta’s book, ‘Plata como cancha: secretos, impunidad y fortuna de César Acuña’, (Lots of Money: Secrets, Impunity and the Fortune of Cesar Acuña) is a journalistic investigation that seeks to examine the career, and political and business influence of Acuña in Peru. It was published during the 2021 electoral campaign, in which Acuña was again running for the presidency.

Roberto Pereira, Acosta's lawyer, told LatAm Journalism Review (LJR) that the judge is demanding from Acosta a standard "absolutely incompatible with freedom of expression," which is to verify the "absolute truthfulness" of what the sources identified by the author have said.

"Quoting is essential to journalists, and this book 'Plata como cancha' is an investigation with testimonies of people who, using their first and last names, recount events they experienced, heard or saw from César Acuña. These are testimonies [previously published by the press], this is not a book citing anonymous sources,” Acosta said. "For me, this is nothing more than the end of an entire intimidation campaign that Mr. Acuña started since the book appeared."

In an interview on the Willax TV channel, Acuña said regarding the sentence that "a person’s honor is beyond freedom of expression."

The conviction also mandated civil damages for 400 thousand soles (about US $100 thousand dollars) to be paid by Acosta, Pimentel and the publisher to the alleged victim, César Acuña. Months ago, after the former congressman and two-time presidential candidate filed the lawsuit, he asked for the seizure of all Acosta's and Pimentel’s assets in order to receive 100 million soles (about US $25 million) for civil damages.

After the publication of the book at the end of February 2021, in the midst of Peru's electoral campaign, Acuña tried to censor the book in March, Acosta told LJR. He sued him and the publisher before the National Institute for Consumer Defense and Intellectual Property (Indecopi, by its Spanish acronym), Acosta said, arguing that the title of the book, “Plata como cancha,” was a phrase coined by him.

The phrase "plata como cancha" means "lots of money" in Peruvian slang, and it was a phrase that Acuña repeated during his campaign as a presidential candidate, when promising public works and jobs in his eventual government.

That first lawsuit ruled in favor of Acosta and the publisher, according to the journalist and author.

"My interpretation is that this has been a trial of intimidation that seeks to restrict the circulation of journalistic investigation," Pimentel told LJR. "First, they tried to do it with a civil lawsuit through Indecopi, ... and when this approach failed, they decided to file a defamation lawsuit against the author, the publishing house and the publisher's editorial director as a kind of ‘exemplary punishment’."

To Pimentel this is a clear message of self-censorship.

Acuña's lawsuit is "a multi-pronged threat to the journalist, the publisher and future journalists and publishers," Pereira said.

Adriana León, director in the area of informational freedoms of the Press and Society Institute (IPYS) of Peru, told LJR that this sentence sets a bad precedent for journalism and freedom of expression in Peru, given that the judge did not evaluate the context surrounding the testimonies presented in Acosta's book, nor the quality of the sources.

"That is precisely what journalists do, collect information from sources, referred to as a documentary source," León said. She also said that Acosta has been diligent and rigorous about his journalistic work.

Acosta said that throughout the legal process he has provided documentation, proof, and evidence of the origin of the information contained in his book. "All the information in the book comes from verifiable sources."

“The information comes from the district attorney’s files and from congressional investigations carried out on Acuña, and from testimonies from his closest circle, from ex-partners, a brother, former workers, former friends, and political enemies. What the book basically does is paint a portrait of how he operates as a politician and as a powerful figurehead in the country. He is a very powerful businessman and holds a lot of political and economic power,” Acosta said.

In an interview with Canal N, the plaintiff's lawyer, Enrique Ghersi, said that Acuña is only seeking to defend his honor. He also pointed out that Acosta never contacted Acuña to corroborate the information in his book, according to a publication from Agencia Andina. However, Acosta said that he did try to communicate with Acuña through his campaign manager, Richard Acuña, the plaintiff's son. And also through the César Vallejo University, owned by Acuña, but he was unsuccessful on both counts, according to the Peruvian site La Mula.

In addition to owning a university and being the founder and leader of a political party with several seats in Congress, Acuña has also been mayor of the city of Trujillo and governor of the Department of La Libertad.

Zuliana Lainez, president of the National Association of Journalists of Peru (ANP) told LJR that in Acosta’s case the National Board of Justice must intervene. In the last four years, the ANP has documented 104 lawsuits against journalists in the country for defamation and crimes against honor, most of them acquitted on appeal.

"But this is the first time we have seen that a ruling, more than on the issue of defamation itself, fully rests on the judge interpreting which source may or may not be credible in the midst of journalistic activity. That seems dire for journalism and for what this can create going forward. It’s an attack against the right to information in the country," Lainez said.

Regarding the large civil damages requested by the judge, Lainez commented that not only is it unfounded, but that it represents an "economic gag" for those who carry out journalistic research in the country.

Together with the ANP, the Peruvian Press Council (CPP) rejected the sentence of the criminal judge Raúl Rodolfo Jesús Vega, who considered that Acosta did not corroborate the quotes used against reliable sources. "This undermines journalistic work and the legitimate right of citizens to obtain public interest information," said both organizations.

The Office of the Special Rapporteur for Freedom of Expression of the Inter-American Commission on Human Rights (IACHR), expressed through a statement its concern about the ruling against Acosta, Pimentel and the publisher, observing the “a significant intimidating and self-censorship effect that affects not only the convicted persons but the entire press and Peruvian society."

In its statement, the Office of the Rapporteur mentions the protection parameters that the Inter-American Court establishes for persons of notoriety or who have voluntarily assumed public responsibilities. According to these parameters, public persons "have voluntarily exposed themselves to a more demanding scrutiny" by society and "their activities leave the domain of the private sphere to insert themselves into the sphere of public debate."

Therefore, the Office of the Rapporteur points out, Article 13 of the American Convention on Human Rights protects diligent information on matters of public interest and maintains that whoever disseminates it should be excluded from all civil or criminal liability.

"This ruling confirms our complaints about how in Peru and other countries, such as Panama and Brazil, there is an epidemic of lawsuits that officials use to gag journalists and the media to avoid criticism and to avoid bringing corruption cases to light, as well as other issues of public interest,” the president of the Inter-American Press Association (IAPA), Jorge Canahuati, stated on the organization's website.

In turn, the IAPA urged the Peruvian Congress to legislate "urgently" so that crimes against honor are not considered criminal, according to its statement.

Various organizations rejected the conviction against Acosta, Pimentel and Penguin Random House in Peru. Human Rights Watch said it was a serious attack on freedom of expression; the European Union asked Peru to respect freedom of the press; and the embassies in Peru of the United States, the Netherlands, Canada, Great Britain, among others, asked the country to respect democracy and freedom of the press and expression.

The organization IPYS registered the signature of seventy journalists who were accredited to ask the Judiciary to allow them to attend the hearing via Zoom. Those who signed also requested that the session be broadcast publicly, given that in principle it would not be. Finally, the conviction hearing against Acosta and Pimentel–which the complainant did not attend–was broadcast by the Judicial Power channel, Justicia TV, via YouTube.

“I am especially grateful to colleagues from all media who joined this request, because basically we’re not defending a person, we’re defending the right that journalists have to investigate and publish without–therefore, as long as all the information is duly documented–becoming the target of judicial intimidation,” Acosta said.