The Brazilian Conference on Data Journalism and Digital Methods – Coda.Br, a pioneering event in Brazil focused on data journalism, will celebrate its third year on Nov. 10 and 11 in São Paulo and has opened registration on its website.

Seven Brazilian verification initiatives presented a letter with suggestions of concrete measures that the Superior Electoral Court (TSE, for its initials in Portuguese) can take to help them fight general disinformation related to the country's elections, whose second round happens on Oct. 28.

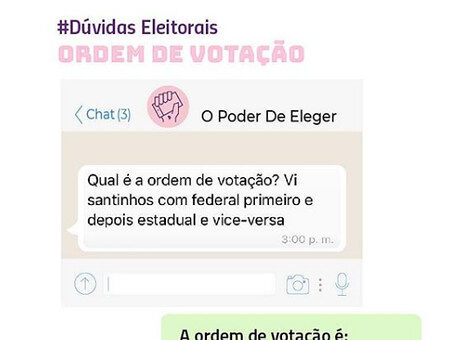

WhatsApp has 120 million active users in Brazil, according to what the company reported in July this year. This number is equivalent to more than half of the Brazilian population, estimated at 208.5 million people.

On Oct. 7, the Brazilian electorate goes to the polls for general elections marked by the intense dissemination of rumors and fraudulent news on social networks, also fomented by the public’s distrust of the press. In this charged political and media environment, journalists have been consistently targeted for doing their investigative and reporting work.

Eighteen journalists who completed massive online Portuguese courses with the Knight Center for Journalism in the Americas were at Google São Paulo on Oct. 1 to attend exclusive workshops on electoral coverage and fact-checking.

The intense mining activity that takes place in a vast area of the Venezuelan Amazon inspired a group of journalists interested in social and environmental issues to work collaboratively across borders.

A journalist in Ceará in northeastern Brazil was shot in the leg and told to stop talking nonsense on the radio.

Last Friday, Sept. 21, marked three months since radio journalist Jairo de Sousa was killed in Bragança, Pará, in northern Brazil, yet no suspects have been identified.

Communicators threatened for doing their work were officially included in the protection program for human rights defenders of Brazil’s Ministry of Human Rights (MDH, for its initials in Portuguese).

The year 2018 has posed several challenges for fact-checking initiatives in Brazil. In addition to general elections permeated by intense political polarization and the new weight of social networks in the dissemination of rumors, fact-checking professionals are also faced with the distrust of the public, still in doubt about the role of fact-checking in the Brazilian media environment.

Brazilian radio journalist Marlon de Carvalho Araújo, 37, was murdered on Aug. 16 inside his home in Riachão de Jacuípe, Bahia, in the northeastern region of Brazil. Police suspect that the crime was motivated by his "aggressive way of providing the news,” reported site G1.

Brazilian journalist, lawyer and writer Otavio Frias Filho died Aug. 21 in São Paulo at the age of 61. Newsroom director for Folha de S. Paulo since 1984, Frias Filho was responsible for the modernization project that made the newspaper a reference around the world for journalism made in Brazil.