The Latin America and Caribbean region is one of the most biodiverse on the planet. Nearly 60 percent of terrestrial, marine and freshwater life is found in this region, according to the United Nations Environment Programme (UNEP).

So it is no surprise that environmental crime is on the rise in Latin America. During the COVID-19 pandemic, illegal exploitation of resources, as well as violence against environmental defenders, increased considerably, mainly in the Amazon region. Among these crimes, illegal mining is among those that are having the greatest negative impact on both the environment and the social fabric of the region.

Thinking about the growing challenges faced by journalists covering illegal mining in the region, the Global Investigative Journalism Network (GIJN) offered the virtual chat "How to investigate the impact of illegal mining in Latin America" on Nov. 17, 2022. The event was led by three journalists who have done outstanding coverage on the illegal extraction and trafficking of mineral resources in the Amazon region.

Joseph Poliszuk, Hyury Potter and Yvette Sierra were the speakers at the Global Investigative Journalism Network's webinar "How to Investigate the Impact of Illegal Mining in Latin America". (Photo: Screenshot)

Yvette Sierra, from environmental news outlet Mongabay (Peru); Joseph Poliszuk, from investigative journalism site Armando.Info (Venezuela); and freelance journalist Hyury Potter (Brazil) spoke about their investigations into illegal mining in their countries and shared lessons learned and best practices to improve coverage of this environmental crime.

When dealing with issues related to illegal mining, it is important not only to investigate extractive activities, but also to track the minerals that are being illegally extracted until, ideally, their final destination is known. This not only helps to provide a more complete picture of the phenomenon, but also to understand its causes and reveal who the main beneficiaries are.

"As the maxim of investigative journalism goes, follow the money," Poliszuk said. "The big challenge is to follow the chain, but it’s so challenging! This is because we are talking about informal and illegal smuggling chains."

However, there are several ways to keep track of the metals, according to the journalists. In a feature story published in February of this year in The Intercept Brazil, Potter told how gold refined in a company accussed of illegal operations allegedly ended up in products of multinationals such as Tesla, Amazon, Dell, and Starbucks.

To come up with this finding, the journalist investigated in the U.S. Securities and Exchange Commission which companies had reported the refinery on their lists of suppliers.

"In the U.S. Stock Exchange, companies are required to provide data on their mineral suppliers. Through this one can link a company that has problems here in Brazil, for example, with gold trafficking," Potter said. "An important way to see the productive chain is to always look for documents in the Judiciary, in the Stock Exchange, to try to better understand what is happening and where they are buying that mineral from."

Journalists investigating illegal mining, added Potter, have to try to break these complex trafficking chains by exerting pressure on any of their links. In a feature story for InfoAmazonia and Diálogo Chino, Potter and fellow Brazilian journalist Fábio Bispo revealed that a Canadian mining giant company withheld information from the U.S. Securities and Exchange Commission about legal disputes related to its plan to build a potassium exploration complex in the Brazilian Amazon. This was according to documents the mining company sent the regulator in an attempt to seek investors for the project.

"If you show investors that they [the mining companies] are lying, their stock goes down and the companies lose money. And that creates a damage to a company that is doing something wrong. That's important data," Potter said.

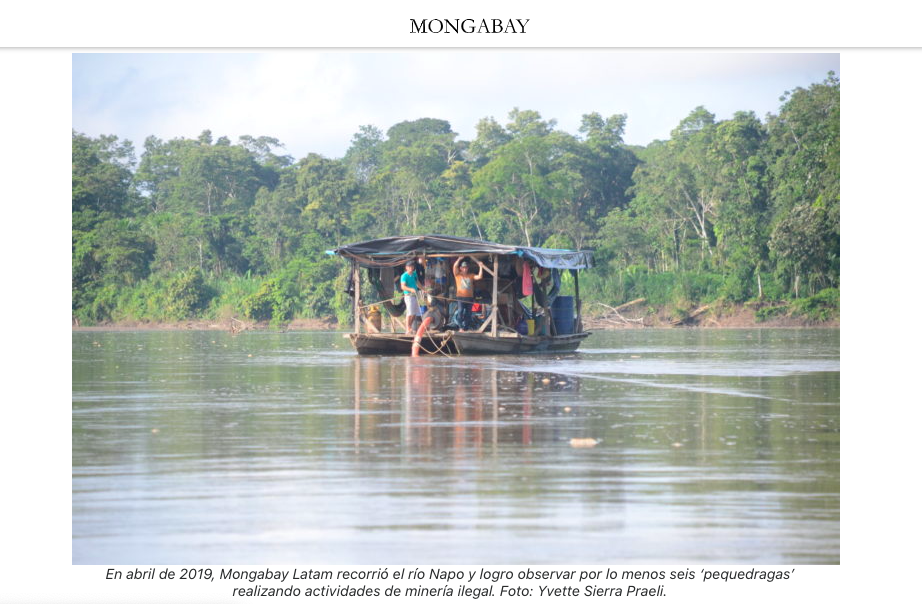

Georeferencing has been a crucial element in Mongabay's investigations into the illegal extraction of gold from the rivers of the Peruvian Amazon using modified boats known as "pequedragas". (Photo: Screenshot)

Similarly, in a Mongabay feature story published in 2019, Sierra found that illegally mined gold from several rivers in Peru was openly traded in trading houses in the city of Iquitos, capital of the Peruvian Amazon. Then, Sierra found that the gold was passed on to collectors to finally be laundered with extraction permits for areas where extraction is permitted.

As a result of Mongabay's work, the authorities launched an investigation that has involved key people in the gold trafficking chain that the news outlet uncovered in its investigations.

"Tracking companies that export gold, companies that sell, companies that stockpile, companies that process gold are ways to follow it [the mineral route]," Sierra said.

For the coverage of mining issues - and in general, for environmental journalism - satellite images are a great ally, especially in areas such as the Amazon region, where access is difficult and dangerous.

For both Poliszuk and Potter, satellite imagery helped them visualize the growth of illegal mining and clandestine airstrip construction areas in the Venezuelan and Brazilian Amazon areas, respectively.

The tools Poliszuk and Potter use to access satellite imagery range from free Google Maps to more specialized platforms. Planet.com, for example, is a paid platform but offers free plans that include limited access to imagery. QGIS, the free geographic information software, has geospatial databases that include imagery.

Mongabay often monitors specialized portals such as Global Forest Watch, the Monitoring of the Andean Amazon Project (MAAP) and the Amazon Network of Geo-referenced Socio-environmental Information, which have access to satellite images that help journalists analyze hard-to-reach places and follow up on environmental crimes, Sierra said.

"This satellite information allows us to have a precise location, we can, with georeferenced points, enter and see what is happening there. In other words, we can see if there is deforestation, if it is large, if it has grown.... We can distinguish, for example, if there are razed fields or if there are mining wells there," Sierra said. "You can know the extent of the area lost, you can analyze it by time periods. And that is often the beginning of an investigation."

Although the three speakers have taken advantage of the benefits of using satellite imagery to investigate illegal mining, they agreed that this technology is not infallible and does not replace traditional reporting techniques.

"It is one more methodology to add to the ones we were already using before, starting with traditional journalism. I do not believe at all that traditional journalism will die, much less in these areas, which are tropical jungles, and where there is a lot of cloud cover. Technology is not perfect and it is not going be useful for everything," Poliszuk said. "I think this is the best way [to do these coverages], mixing different methodologies."

The speakers also agreed that capturing information on maps helps to tell stories with a more complete dimension and offers the reader a contrast between different phenomena occurring within the same geographical region.

The series "Corredor Furtivo", by Armando.Info and El País, shows on satellite images the presence of illegal mines, clandestine airstrips, criminal groups and indigenous territories in the Venezuelan Amazon. (Photo: Screenshot)

Georeferencing was central to the "Corredor Furtivo" [clandestine corridor] series of feature stories, jointly produced by Armando.Info (Venezuela) and El País (Spain), and published in early 2022. This special series contrasts through map visualizations different layers of data, including the presence of illegal mines, clandestine airstrips, criminal groups, and Indigenous territories in the Venezuelan Amazon.

With the support of a satellite image analysis algorithm developed by Earthrise Media, Poliszuk and his team located 3,700 mines, many of them in territories where no mining is allowed.

"The idea [of 'Corredor Furtivo'] was to go beyond denouncing or narrating from a single location," Poliszuk said. "It was no longer just a work where technology was merely used, but rather technology helped us know where to go."

Similarly, Potter located on a map all mining requirements registered by the National Mining Agency (ANM, by its Portuguese acronym) in Brazil's Amazonian territory and contrasted that data with Indigenous territories and protected areas in that territory.

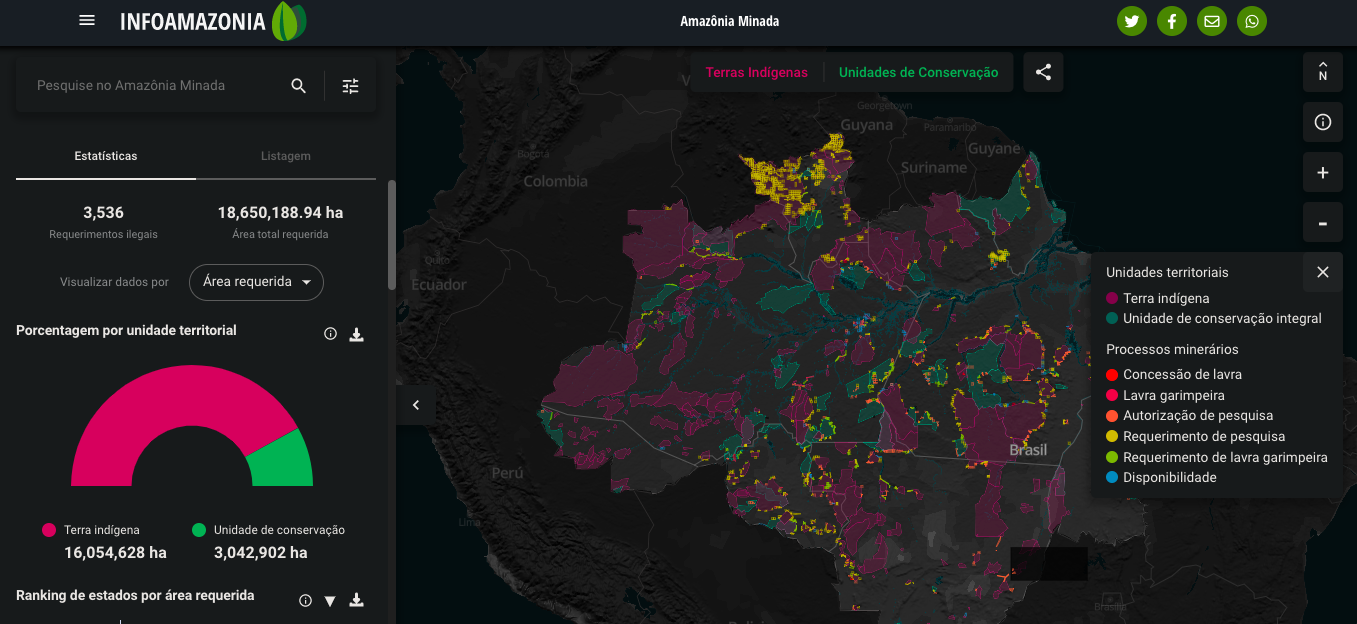

The result was "Amazônia Minada [Mined Amazon]" an interactive platform within the InfoAmazonia website that revealed that the ANM has received thousands of requests for mining within Indigenous territories and conservation areas, where all mining activity is prohibited by law.

"There are now 2 thousand 467 requests for [exploitation of] minerals. That doesn't mean that these are mines that are being exploited, but all of this would affect Indigenous lands in the Amazon," Potter said.

A similar geo-referenced contrast is shown in Mongabay's "Comunidades en resistencia [Communities in Resistance]" special. On a map, the news outlet cross-referenced data on the location of Indigenous communities in five Amazonian regions of Peru with information on illegal crops, illegal mining and deforestation. In this way, they were able to locate the Amazonian Indigenous communities most impacted by environmental crimes.

Georeferencing was also crucial to Mongabay's investigation of illegal gold mining in Peruvian Amazon rivers. Indigenous organizations that have spent years geolocating with GPS systems the "pequedragas," as they call the boats adapted to extract gold from the bottom of the rivers, approached the news outlet in order to denounce the mineral exploitation in their territories.

"Our research began precisely with information from Indigenous communities living along the Napo River," Sierra said. "We went to see what was happening and the georeferencing was very useful for us to know which places we were going to enter. Since we knew the places where these 'pequedragas' were, we were able to get much closer."

Illegal mining involves armed groups or organized crime in inhospitable and difficult to access places. For this reason, Sierra, Poliszuk and Potter believe that careful preparation is essential to reduce the risks when investigating this type of activity.

"Amazônia Minada" is an interactive platform of InfoAmazonia that shows mining permit applications within indigenous territories and conservation areas in Brazil. (Photo: Screenshot)

"First, we do a pre-production to know where we are going. You have to plan for everything, from [insect] repellent to health issues," Poliszuk said. "Speaking of illegal activities, it's good to find local people to serve as scouts or guides. Alliances with local journalists are always good, they really add up. That way we can cover not only more territories, but more topics."

The three journalists also agreed on the importance of being transparent with sources. This includes avoiding hiding a journalist's identity, using hidden cameras or deceiving the people involved to gain their trust.

"There's a whole ethical debate about these issues, but it also depends on each story. It depends on what we're looking for," Poliszuk said. "You need to look for sources and there is no philosopher's stone or method for how to win over those sources. A lot of times we’re talking about people who are committing crimes. I think not fooling them is a premise that has worked for us."

The pre-production of any story on illegal mining should include putting together a travel itinerary with contact information for each location and sharing it with the newsroom, Sierra said.

"Another very important matter is to have an ongoing connection with your editors," she said. "Specifically say 'I'm going to go to such-and-such a place, I'm going to be at this place.' Specify, if possible, how long you're going to be there, if you are going to enter a place without connection, and try somehow to communicate every day with your base, with your editors,"

Sierra advised carrying SIM cards from all the regions' cell phone providers to try to always have coverage.

Potter shared that this year, in the wake of the murders of British journalist Dom Phillips and Brazilian Indigenous activist Bruno Pereira, he redoubled the security measures he takes when reporting in the field. This includes the use of a satellite tracking device that sends location data to his newsroom.

"You can send a location message every five minutes of where you are," Potter said. “Someone in the newsroom, in the city, is watching my pace and the pace of the photographer and the team that's in the field.”

In addition to measures before and during on-site investigation, it is important for journalists to work collaboratively on stories that need to be told on a large scale, but that could put their physical integrity at risk.

"If organized crime and all these illegal trafficking networks operate globally, we journalists also have to get on the same page and take a global view," Poliszuk said. Along with Potter, he is part of the Pulitzer Center's Rainforest Investigations Network (RIN), which promotes cross-border collaboration on stories about climate change, corruption in the rainforest regions of the world, including the Amazon.

While it is important to put a human face on stories, when covering issues related to criminal organizations it is essential not to put at risk the sources who collaborate with the journalistic investigation.

In the case of illegal mining in Latin America, it is very common for local inhabitants, activists and journalists to suffer threats against their physical integrity, so it is necessary to be very careful when revealing their identity, the speakers said.

Potter showed the audience the satellite tracking device that he carries with him during his in field reporting in the Brazilian Amazon. (Photo: Screenshot)

"There are people who come up and say 'I want to give an interview and tell what is going on.' But a lot of times they don't know what can happen next after you publish their name," Potter said. "All of that has to be explained to them well, to be absolutely certain they are well aware of the risk they are talking."

With the recent increase in the number of environmental leaders, journalists and activists attacked and killed in the region, Mongabay has chosen to identify sources who may be at risk by first name or by aliases only.

"Not only are they people who live under threat, but they also stay in those places, as is the case of the inhabitants of Indigenous villages. They live there, so they face risks every day," Sierra said. "There are cases of leaders murdered in other countries, so we are very careful to maintain their physical integrity and not to make visible the people who are facing these threats."