Three years ago, in the midst of the COVID-19 pandemic, a group of Argentine journalists from different media began to notice that, although in the capital Buenos Aires there were a wide variety of traditional and independent media practicing journalism in a relatively safe way, in the provinces in the interior of the country the story was very different. Especially when practicing investigative journalism on topics such as corruption and abuses of power.

Faced with this reality, members of the group, led by Edgardo Litvinoff, then-editor of the newspaper La Voz del Interior, and Sergio Carreras, author and political columnist, joined forces to create a collaborative media outlet. It would have a horizontal structure and journalists would work in a network, producing investigative reports based on public data to alleviate the news vacuum that exists in the country.

“We had a lot of problems doing investigative journalism on issues related to transparency, access to information and corruption,” Litvinoff, who is based in Córdoba, told LatAm Journalism Review (LJR). “We began to notice very clearly in our media that there was a great news desert in most Argentine provinces because there are very few media outlets and the media that do exist have become excessively dependent on official advertising.”

The Ruido team includes journalists in each of Argentina's 24 provinces, as well as open data specialists. (Photo: Screenshot of Ruido's Instagram profile)

The journalist said that they know of some media outlets in the provinces whose income from official advertising from local governments was up to 70 percent. That, he said, translated into pressure from local authorities on the media and journalists, the impossibility of carrying out journalistic investigations and self-censorship.

According to the 2021 study News Deserts in Argentina, by the Argentine Journalism Forum (FOPEA, for its acronym in Spanish), up to three quarters of the territory of that country have scarce or weak conditions for the practice of professional journalism.

Litvinoff and Carreras concluded that the best way to try to change that reality was by creating a collaborative network of local journalists who would join forces to approach coverage from a macro perspective. This is how Ruido (or Noise) was founded at the beginning of 2021.

“[Ruido] is the response to the state and political dependency that the media have due to their financial crisis,” Fernando Ruiz, professor of journalism at the Austral University in Buenos Aires and former president of FOPEA, told LJR. “It is 'flashmob' journalism, a national newsroom with good professionals that comes together like a spontaneous orchestra to investigate a critical and sensitive topic. ‘Flashmob’ cooperation is key to addressing issues that are left off the agenda, or are not addressed with the necessary depth.”

Ruido is currently made up of at least one collaborating journalist in each of the 24 provinces of Argentina, in addition to open data specialists and five people in its central newsroom.

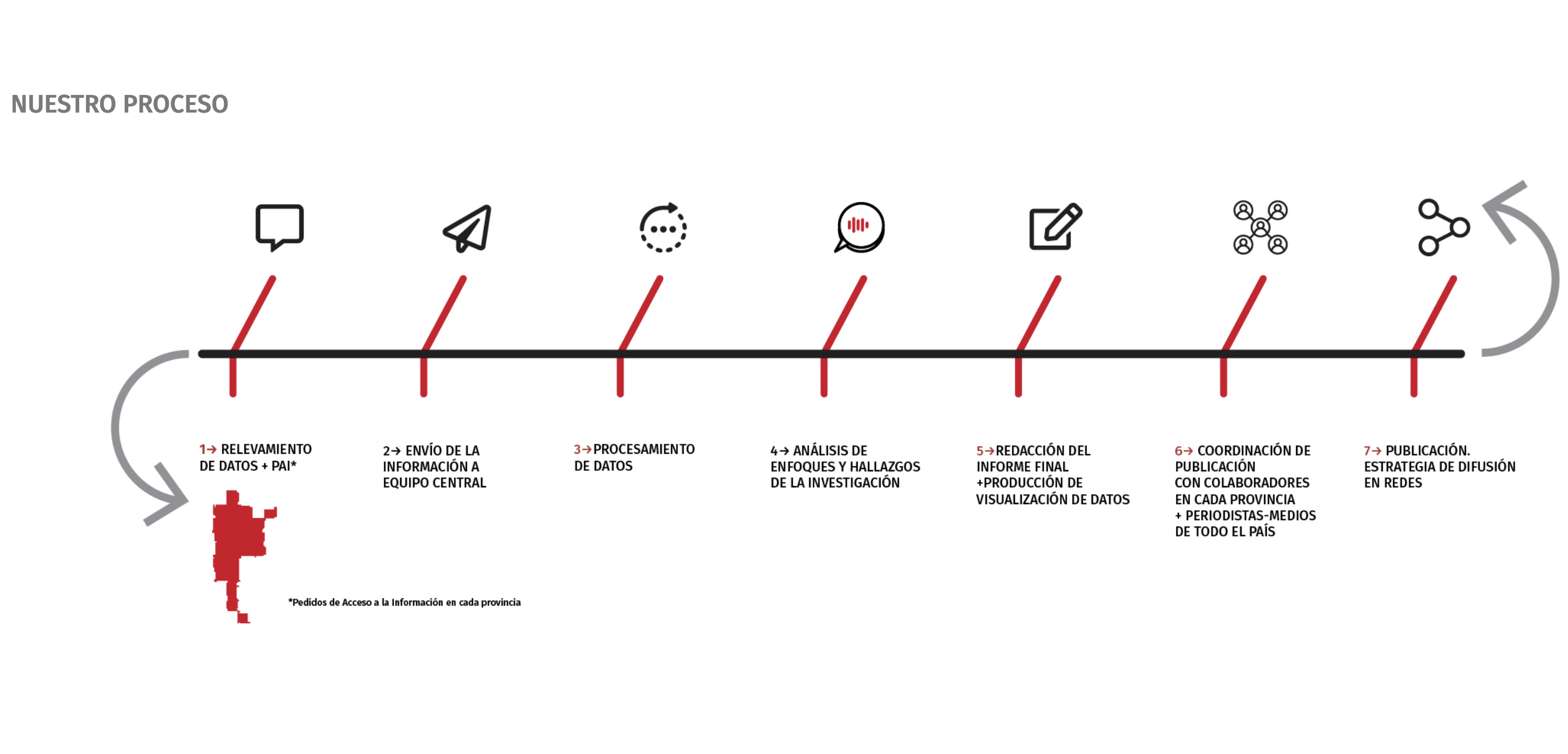

The journalists produce reports based on journalistic investigation that are national in scope. These investigations are based on requests for access to public information, which, Litvinoff said, are Ruido's main tool.

Each of the investigations begins with requests for access to public information presented in each of the 24 Argentine provinces, according to local laws. The team has prepared 24 access to information request models, given that each province has its own law on the matter, with the exception of five provinces that do not have access to information laws. Argentina also has a federal law on access to public information.

“Every time we make a request, we create a protocol to obtain the same indicators in each of the provinces. Then, we process that information and create journalistic content,” Litvinoff said. “There are five provinces that do not have a law on access to information, but we invoke the National Constitution and international laws that are already norms in Argentina.”

Although Argentina is not among the countries with the greatest transparency in the world (the country obtained a rating of 50 out of 100 in the Transparency category in the 2021 Open Budget survey), Litvinoff said that the federal government has mechanisms for access to information that are more or less organized. But at the provincial level, there is a very different story.

Although mechanisms exist in most provinces, they are deficient, according to Litvinoff. On many occasions, public agencies do not respond to requests for information, or take a long time to do so. When information is obtained, it is delivered in formats in which even its open data experts find it difficult to find the requested information.

“What little there is is very difficult for journalists to navigate,” Litvinoff said. “If we’re looking in a database and we want to know how much a public work project costs, it is almost impossible to navigate. Even though the province says that the data is there, it is not disaggregated in a way in which we can determine how much a public work project costs.”

According to Litvinoff, in none of the investigations they have carried out so far have they had full access to public information. In all investigations, some collaborators from the provinces have to resort to other methods to obtain information, including legal resources.

“Our collaborator in Tierra del Fuego… was able to take [the data request] to the final stages. But even with court rulings, it has been very difficult to access information,” Litvinoff said. “In another case, they gave [another collaborator] access to a file that had 15,000 pages and told him that he had to pay for copying those 15,000 pages, which was the same as telling him that they were not giving him the information.”

In addition, Ruido based its methodology for access to information requests on what Chicas Poderosas developed during its 2020 collaborative and national investigation based on public data, “Los Derechos no se Aíslan” (The rights do not isolate themselves). For this project, Chicas Poderosas carried out requests for access to public data on women's sexual and reproductive health during the pandemic in all provinces of Argentina.

Every Ruido investigation begins with requests for access to public information in each of Argentina's 24 provinces. (Photo: Screenshot of Ruido's Instagram profile)

“They saved us a lot of work at the beginning of this project,” Litvinoff said. “We were able to have an Excel that they had already made about what the Access to Information Law was in each province, what requirements are needed, how many days they had to respond. For us it was very useful because it immediately allowed us to present requests for access to information in a much easier way.”

The obstacles to accessing information, added to the work of processing information and the double verification process they carry out, mean that the completion time for each investigation can last up to six months. One of the network's current challenges, Litvinoff said, is to reduce these times to increase the frequency of publication and, as a consequence, be able to aspire to more funding.

So far, Ruido's sustainability system has been based on international funds, to which the network applies prior to each investigation. In 2023, Ruido began experimenting with crowdfunding to fund an investigation currently underway on provincial legislatures.

Also last year, the network received funds from the Impulso Local program, the Association of Argentine Journalistic Entities (Adepa), the International Center for Journalists (ICFJ) and Meta. This support was used to redesign its website and build its crowdfunding platform.

This financing model has allowed the organization to provide permanent employment to two members of its team, as well as distribute resources among the collaborators of its network in the 24 provinces of the country.

One of Ruido's main missions is to strengthen citizens' access to public information, even if that means giving up scoops.

“We are clear that we are a media outlet that does investigative journalism against corruption, but in the way we disseminate it, we are much more interested in the content being disseminated than in having a scoop,” Litvinoff said. “Each investigation is taken up by between 40 and 60 media outlets that reproduce the information.”

Ruido's dissemination strategy consists of distributing its reports free of charge to journalists in its network, as well as to a list of local and national journalists and media outlets with which they have an alliance. It’s not just the reports that are distributed, but also all the content that was used to carry out the investigation: databases, infographics and images, so that each media outlet or journalist can use the raw information to take their own approaches.

The content is sent a week before its publication under an embargo and under the agreement that it must be published on the same day and at the same time as the Ruido investigation.

“Every time we publish a report, we send an email that briefly says what it’s about and we send the link with the content. Afterwards, each journalist from each province is also in charge of disseminating that same email among their colleagues,” Bárbara Maidana, audiences coordinator for Ruido, told LJR. “We agreed on dates and a time to all go out together and make more ‘noise,’ precisely. That gave us more results than each one publishing when it had a place on the agenda.”

Maidana added that the main audience they cover with this distribution strategy is the sector of journalists, researchers and academics. However, they also target the general public. For this, the audiences team produces articles derived from the main reports about each province and distributes them on social networks.

¡Ganamos con @RuidoRed el Premio Mayor al Periodismo de Investigación de @FOPEA por el informe sobre nepotismo en las provincias! Este año también logramos un premio Adepa. ¡Y nos vamos a México con "Los dueños del litio"! https://t.co/awdpPkeOJa pic.twitter.com/8mgGuC497L

— Edgardo Litvinoff (@edlitvin) December 2, 2023

Distribution on digital platforms emphasizes publishing hard data and engaging the audience, above all on Instagram, Maidana said. In order for the data derived from the investigations to reach the audience, they use surveys and other interactive elements offered by Instagram.

“A strategy that we are preparing for this year is to make more explanatory videos, because seeing the information in an infographic or in a graph may not be as accessible to the general public, and it is more accessible for them to receive that information through explanatory videos,” the journalist said. "It is something that we proposed this year: to be able to explain the topics more and not stop at those who perhaps can understand the graphics better."

In the end, what Ruido seeks with its different ways of disseminating its reports is for sensitive information about public administration – produced by its network of collaborators – to reach the public, regardless of the medium.

“This is a bit like rugby: the ball has to reach the opponent's in-goal, it doesn’t matter which player does it. Here the in-goal is the public. The information has to reach the public no matter what. Therefore, when journalists cannot publish information of public interest in their media outlet, these mechanisms exist to continue fulfilling our social role,” professor Ruiz said. “Ruido is, therefore, a key mechanism.”

According to the former president of FOPEA, Latin American initiatives like Ruido are a response to the different types of crises facing journalism. Although there are still not similar projects in Argentina, several forms of cooperation between journalists similar to Ruido have existed in Latin America, following episodes of violence.

“In Colombia, Proyecto Manizales was created following the murder of journalist Orlando Sierra, the IAPA with Ricardo Trotti also supported joint investigations among editors on the northern border of Mexico that were completely devastated by drug violence. Or the project Frontera Cautiva, in which FLIP and Fundamedios among other organizations participated to investigate the murders of three Ecuadorian journalists. And recently we had the magnificent Proyecto Rafael in the region [after the murder of Colombian journalist Rafael Moreno],” Ruiz said. “Ruido is a similar cooperative effort –although fortunately without a prior misfortune–, which allows for group investigation on essential issues for citizens.”

But for Litvinoff, Ruido aspires to become an organization similar to ProPublica, the independent, nonprofit media outlet based in New York, that produces investigative journalism in the public interest. Although they also identify with the collaborative and transnational work that CONNECTAS does, from Colombia.

The networking methodology allows Ruido, based on multiple hyper-local stories in each province, to have an impact at the national level.

“The most positive thing we have is the scope, because there is no other Argentine media outlet that is truly federal and transversal, and with investigations that are of interest at the national level and for all the provinces,” Litvinoff said. “Suddenly in this hyperlocalism that we reveal, we find stories of great national impact.”

Ruido's investigation and publication methodology allows any media outlet or journalist to use its reports to find their own approaches. (Photo: Screenshot of ElRuido.org)

One of the impacts of the organization's work is that it has managed to expose the level of opacity that reigns in some provinces. After their first investigations, local governments that did not respond to public information requests as required by law were exposed. Although in several provinces it is still common for collaborators not to receive a response, some of the provinces that did not respond have begun to do so, even if it is to say that they do not have the information, the journalist said.

“Now [local governments] are more attentive to the fact that if we make a request for access to information, they have to answer it because otherwise they will be exposed as one of the provinces that does not respond. That, for example, is a positive reaction,” he said. “Or in places where this lack of access to information has gone to court, the fact that the justice system has said that the government has to deliver the information is another positive reaction.”

In December 2023, Ruido won the Major Prize for Investigative Journalism in Argentina, awarded by FOPEA, thanks to a report on alleged nepotism in the Argentine provinces. A month earlier it also won two ADEPA Awards in the Investigative Journalism category, for the investigations “Official advertising: more than half of Argentine governors do not respect the public ethics law” and “The owners of lithium in Argentina.”

However, for the Ruido team, the main impact that the media outlet’s work has had is – paradoxically – silence. In its years of existence, Litvinoff said, none of its investigations has been refuted. They attribute this to their rigorous fact-checking process but also to coordinated collaborative work.

“We have never had any public complaint from any official and they choose silence,” he said. “In that sense we see that we are protected, not so much because it is a network or because of the way we work. The way we check the data seems to me to be our greatest shield.”