In the year leading up to Nicaragua’s presidential election on Nov. 7, President Daniel Ortega implemented increasingly strict limitations on press freedom— a move critics say is part of a years-long campaign to silence Ortega’s political opposition.

Tribute to those killed during citizen protests in Nicaragua in April 2018. (Photo: Jorge Mejía Peralta/CC BY 2.0)

“It's a very, very dire situation that we're going through in Nicaragua,” Nicaraguan journalist Cindy Regidor said at a briefing on the Central American country and its press held by the Committee to Protect Journalists (CPJ) and Foreign Press Association. “At this point, our colleagues are no longer putting their names in their articles, no bylines, because that also poses a threat after dozens of us have been interrogated by the prosecutor's office as a way of intimidating us.”

Press freedom in Nicaragua has been declining since 2018, when proposed social security cutbacks led to a rash of protests calling for the president’s resignation. Ortega’s Sandinista regime responded by deploying paramilitary forces against its citizens, an act of violent repression that left hundreds of Nicaraguans dead. Journalists covering the protests were singled out by the government and subjected to physical and online harassment, surveillance, raids on news outlets, and in some cases, imprisonment.

On the night of April 21, the most lethal case against a journalist occurred when Ángel Gahona was shot in Bluefields during a broadcast on Facebook Live. He was covering a clash between riot police and demonstrators.

In the three years that followed, the Nicaraguan government implemented several additional measures to deter independent journalism.

Police raided and occupied the headquarters of media outlet Confidencial in December 2018, and then took over its new editorial offices for a second time in May 2021. The production facilities of Nicaraguan TV news channel 100% Noticias were also raided and taken over in December 2018.

During these years, scores of Nicaraguan journalists have been forced to go into exile.

In October 2020, Sandinista party leaders passed a cybercrimes law, also called a “gag law.”. The legislation penalized publication of false information with fines and up to four years in prison. The law does not specify guidelines for what qualifies as false information, leaving that verdict to the judiciary’s discretion.

In the same month, the country’s National Assembly approved the controversial “Foreign Agents Law,” requiring all Nicaraguans who work for “governments, companies, foundations or foreign organizations" to register with the country's Ministry of the Interior. This includes journalists who work with foreign organizations or receive international funding, and foreign correspondents based in Nicaragua.

“Immediately for us, they set off alarm bells,” Natalie Southwick, the program coordinator covering Latin America and the Caribbean for CPJ, said at the organization’s briefing. “If you're receiving funding from really any entity outside of Nicaragua, you have to register as a foreign agent. Someone like Ortega will see a law like this used successfully to increase censorship and limit expression.”

Press freedom organization Violeta Barrios de Chamorro Foundation stopped operating following the approval of the Foreign Agents Law, but was still targeted by the Ortega regime. Former director of the foundation and potential presidential candidate, Cristiana Chamorro, was placed under house arrest in early June and charged with money laundering and mismanagement of the foundation.

Chamorro wasn’t the only one in the government investigators’ crosshairs.

María Lilly Delgado, a Univision correspondent based in Managua, was called to testify without notice in relation to the Chamorro investigation. When she arrived to give testimony— the 12th journalist summoned in less than a month— officials with the public prosecutor’s office stated her lawyer wasn’t allowed to accompany her to the interview.

“We told them that we would each go in with our lawyers separately, but they insisted that the lawyers could not be there because we were there as witnesses. They said if we insisted [on] the presence of our defense lawyers, the prosecutor’s office would have to change us from the status of witnesses to defendants,” Delgado said, according to a press releasefrom the National Association of Hispanic Journalists.

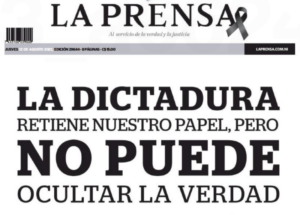

La Prensa's cover from Aug. 12. (Screenshot)

In August 2021, newspaper La Prensa, Nicaragua’s only remaining national daily print newspaper, announced it was going digital since the government was withholding its printing supplies. The following day, Sandinista police raided its headquarters.

The absence of print media and censorship of television outlets has a significant impact on news availability in Nicaragua— less than 30 percent of the country has access to the Internet.

“Nicaragua is the second poorest country in Latin America. I come from a low income neighborhood and I was the only one in the whole neighborhood, in the whole five blocks in my neighborhood, that had internet access at home,” Nicaraguan journalist Yamlek Mojica said at the CPJ briefing. “So, people have nothing to get informed. There's very few options for Nicaraguan people to know what is happening in Nicaragua if you are poor, and a lot of people are poor in Nicaragua.”

In August, police detained La Prensa publisher Juan Lorenzo Holmann on charges of alleged fraud and money laundering. Journalist Carlos Fernando Chamorro, director of the digital news outlet Confidencial and the son of a former president who defeated Ortega in 1990, was also accused of money laundering less than two weeks after Holmann.

“They say that this is because they're conducting an investigation on an alleged case of money laundering, but in reality the interrogations are all about who our sources are, how we work, how we decide how to cover the issues in Nicaragua, if we're being paid by the CIA,” said Regidor, who reports for Confidencial.

Foreign journalists have also faced roadblocks in Nicaragua in the months leading up to the presidential election. In June, a New York Times reporter was not allowed into the country, despite meeting all of the legal and health requirements for entry. The same happened to French journalist Frédéric Saliba from Le Monde in October. He was informed that his plane ticket had been cancelled by the airline a day before his flight, for “migratory reasons,” according to the French newspaper. On Oct. 28, Confidencial reported that a team from Honduran newspaper El Heraldo were expelled from the country after entering through a border checkpoint.

Ortega has faced international condemnation — notably from the United States, Canada, and the European Union — due to his regime’s crackdown on journalists and independent media. The Nicaraguan government refutes accusations of media repression, claiming instead that it’s protecting its citizens from fake news. The vice president and spokesperson for the Ortega administration Rosario Murillo called journalists “evil,” and “communication terrorists,” in an interviewwith Nicaraguan state-run media in June 2021.

From L: Nicaraguan Vice President Rosario Murillo and President Daniel Ortega (總統府, CC BY 2.0 via Wikimedia Commons)

“The chattering magpies, everyday they invent anything to sow terror in people,” Murillo said. “If it is not one thing, it is another, they are always deploying, wanting to instill fear and our people know how they lie, how they are evil, hypocritical, destructive, criminal, terrorist and communication terrorists as well.”

Just on Nov. 1, Meta’s Facebook announced that the Nicaraguan government has been running a troll farm since 2018 to spread disinformation, smear the opposition, and praise the government, as the Financial Times reported. For the month of October, it said it took down about 1,500 accounts, pages and groups on Facebook and Instagram.

Ahead of the upcoming elections, CPJ published a list of eight threats to press freedom to watch out for, including imprisonment, newsroom raids, police harassment and surveillance, judicial harassment, administrative harassment, self-censorship, exile and decreased access to public information.

Despite continued repression by the government, many Nicaraguan journalists aren’t backing down from reporting on the upcoming election.

“Even people that have relocated to other places are creating small projects that allow them to continue reporting on what's happening in Nicaragua...there's this really deep commitment to continuing to tell the stories of what's happening in Nicaragua even from beyond the borders,” Southwick said.

“It's going to be very hard for [journalists] to cover the voting process on Nov. 7, but I think that despite all those risks, we're still going to do it,“ Regidor said. “We're just going to be very cautious.”

Glorie Martínez, the author of this article, is a student at the University of Texas at Austin. She completed this post as part of the course "Reporting Latin America."