Although trust in the news increased in 2021, countries in Latin America have rates lower than the world average. This is one of the main conclusions of the tenth edition of the Digital News Report by the Reuters Institute, published this Wednesday, June 23rd. A version in Spanish is forthcoming.

Globally, trust in the news grew six percentage points and reached 44 percent. That is, for every 100 people who participated in the survey, 44 responded that they trust the news most of the time. Finland (65%) leads the world rankings for trust in the media while the United States ranks lowest on the list (29%).

Newman: 'media have played a critical and valuable role in informing people at a time of crisis’

“Different factors are at play in different countries but to some extent, this is recognition that the media has played a critical and valuable role in informing people at a time of crisis. COVID has also squeezed out some of the partisan debates that we know undermined news media trust – at least in some countries – and that probably contributes to the rise in trust too,” Nic Newman, one of the survey authors, told LatAm Journalism Review (LJR). “Of course, the U.S. is a bit of an exception here in that we have seen divisive debates over a 'stolen election' and race. It is one of the few countries where trust in the news has not gone up this year.”

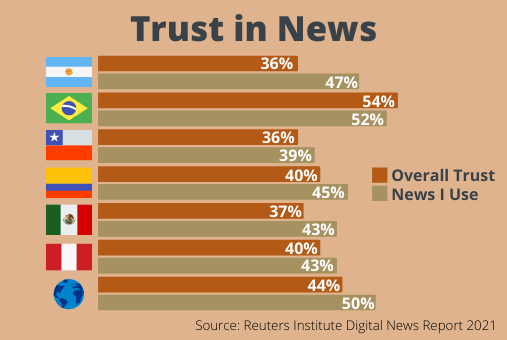

In the six Latin American countries included in the report, overall trust in the news reaches 40.5 percent. Trust is lowest in Argentina and Chile (36%) and highest in Brazil (54%). Despite this, all countries followed the trend of increasing trust in the news, with the exception of Mexico (37%), where it fell by two percentage points to reach 37 percent. In Colombia and Peru, included for the first time in the report, trust in the news is 40 percent.

In Mexico, President Andrés Manuel Lopéz Obrador’s daily attacks on the press explain the trend of increasing public mistrust, according to the report. In the mañaneras, as the president's daily morning briefings broadcast live on TV are called, "journalists who challenge him find themselves on the end of a verbal bashing." While "the president is getting more popular, and people are trusting the media less."

In Argentina, one of the justifications for low trust in the media (36%) is the polarization of coverage, with media that support and others that oppose the Casa Rosada, the report says. Even so, confidence grew by three percentage points.

In Chile, the effects of popular demonstrations at the end of 2019, before the pandemic, still explain the level of trust in the media. There was a growth of six points in 2021, the highest on the continent, but the current rate of 36 percent is still 10 points below what was recorded before the protests.

Brazil is a unique case in the region, with a trust index of 54 percent. According to the Reuters Institute report, "the uncertainty brought about by the health crisis apparently strengthened people's appetite for reliable information."

“The major Brazilian press adopted a posture aligned with the recommendations made by science. Unlike what happens in the United States, for example, there are no news channels questioning the effectiveness of vaccines,” journalist Rodrigo Carro, who wrote the section dedicated to Brazil in the study, told LJR.

Mitchelstein: ‘Argentine citizens are distrustful of the media in general, but trust in their own criteria and ability to discern what is true from what is false’

The report also records the level of trust in media that respondents use to obtain information. In Argentina, it reached 47 percent, 11 percentage points more than the average trust of media in general.

“Although this question was not asked in the survey, we know from our work that the Argentine citizens are distrustful of the media in general (and other institutions), but trust in their own criteria and ability to discern what is true from what is false, so it is not surprising that they have more trust in media they choose,” Eugênia Mitchelstein, director of the Department of Social Sciences of the University of San Andres in Argentina, told LJR.

The global average of trust in the media that respondents consume is 50% (six points higher than the general trust). In Brazil, it is 52%. Next comes Colombia (45%), Mexico (43%), Peru (43%) and Chile (39%) (see graph).

Confidence in the media is lower in Latin America compared to the world average. Art: LJR

According to Carro, the fact that Brazil is the only country in the region where respondents trust the news they consume (52%) less than news in general (54%) is probably due to the high use of social media as a source of information. Brazilians are among those who get the most information, for example, by WhatsApp (43%) and Facebook (47%).

“The pandemic, added to the polarization that has taken over social networks and instant messaging applications in recent years, apparently led Brazilians to question the credibility of the content broadcast by these channels,” Carro said.

The survey also shows that some digital native investigative media outlets are already being cited among the most consumed and the most reliable outlets in Latin America. These are the cases of Ojo Público and IDL-Reporteros (Peru), CIPER (Chile), La Silla Vacia (Colombia) and Animal Politico (Mexico).

Cueva Chacón: ‘digital native media that have emerged in the last five to 10 years in Peru are seen as more independent’

“In the specific case of Ojo Público and IDL-Reporteros, these media outlets have already been producing investigative journalism for about a decade. At the risk of angering investigative divisions of media such as La República and El Comercio, I would dare to say that they are the heirs of the great investigative journalism that existed in Peru in the 1980s and 1990s,” Lourdes M. Cueva Chacón, of San Diego State University, told LJR. "In addition to that, the digital native media that have emerged in the last five to 10 years in Peru are seen as more independent.”

Print media and digital payments

If on the one hand the COVID-19 pandemic has contributed to an increase in confidence in the news, on the other hand it has placed another nail in the coffin of the print media, “partly due to restrictions on movement and partly due to the associated hit to advertising revenue.”

The sharp drop in print media was greatest in richer countries where newspaper circulation is traditionally higher. In Latin America, this acceleration represented the end of some paper publications. In Chile, the popular newspaper La Cuarta stopped circulating in print format and La Tercera, from the same group, suspended the print edition on weekdays.El Mundo (Colombia), El Bocón (Peru), and Jornal do Commercio (Brazil) also ended their print editions. Also in Brazil, O Globo removed the print edition from newsstands in the capital Brasília and Época magazine, from the same group, stopped circulating.

“As elsewhere, print sales have been badly hit, accelerating the structural trends of the last few years. Restrictions on movement and commuting have affected newsstand sales across the region and in some cases, people were worried about catching the virus from printed newspapers,” Newman said.

In other cases, the economic crisis generated by COVID-19 led to the creation or deepening of paywall systems. This is the case of Colombia’s El Tiempo, which launched its own in October 2020. Argentina’s Perfil launched its system in September 2020. “Every day it becomes more difficult for us to sustain structures that allow us to carry out journalism that is critical, incisive and uncomfortable for power and by definition expensive,” wrote Agustino Fontevecchia, executive and digital director of the publication, upon announcing the paywall to readers.

However, “overall progress remains slow. Across 20 [rich] countries where publishers have been actively pushing digital subscriptions, and that we have been tracking since 2016, we find 17 percent saying that they have paid for some kind of online news in the last year,” the report says. “The vast majority of consumers in these countries continue to resist paying for any online news”.

In the six Latin American countries investigated, the rate of readers who paid for online news is 15 percent on average among survey respondents. In this regard, Mexico had the highest result (18%), with Brazil second (17%), followed by Peru (16%), Argentina (15%), Colombia (15%) and Chile (12%).

“The ability to pay in Colombia is also limited and many families prefer to have a Netflix subscription to access paid information services. The low intention to pay shows that the paywalls model must be complemented with other strategies to obtain resources from different sources and to diversify the business in an innovative way,” Victor Garcia Perdomo, director of the doctorate in communication at the University of La Sabana, in Colombia, told LJR.

According to Newman, the numbers for Latin America need to be evaluated with caution, as the survey sample has a higher proportion of people with a higher level of education and who are more likely to consume paid news.

“Industry data tells us that the numbers (as a proportion paying for news) is low in Latin America. Even if some publishers in Brazil and Argentina (and now Colombia) have been asking people to pay for some time, the number of paying subscribers is still very low as a proportion of the overall population,” Newman said. “Why is that? Probably a mix of factors, lower usage of reading/print than many European countries, lower disposable income, and the fact that most news is free on the internet. Until recently there have been very few publishers even trying to charge for online news.”