On a visit to relatives in the western Irish town of Westport, Ioan Grillo, an English-born journalist who has lived in Mexico for more than two decades, realized that stories of drug traffickers [narcos] from Latin American countries amassing multi-million dollar profits, becoming popular idols and escaping national and international authorities hold a special fascination for people far removed from that reality.

While talking about his experience covering the violence generated by the rivalry between the Los Zetas cartel and the Sinaloa cartel for control of Nuevo Laredo, a city in the state of Tamaulipas bordering Texas, Grillo realized that, told in the right way, these stories of violence can also create empathy among people from any latitude who may not know the context and causes of these phenomena.

Ioan Grillo has been covering organized crime in Mexico for more than two decades. (Photo: Courtesy)

"People have a human interest in these stories, about what's going on, about - for example - that paid hitmen were trained as children. It's interesting how I see it, how I tell it, how people hear it and how they react to these things," Grillo said in an interview with LatAm Journalism Review (LJR). “In the end, it's how you tell a story, how you take this story into people's homes.”

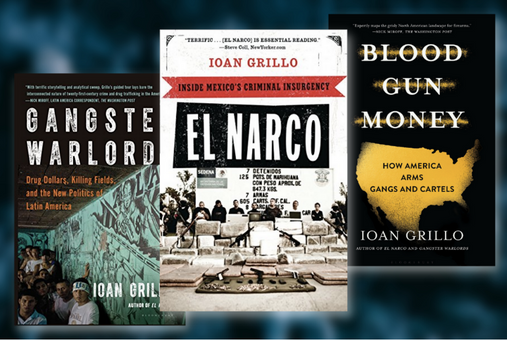

The journalist received the Gold Medal of the Maria Moors Cabot Awards 2022 from the School of Journalism at Columbia University in New York on July 21. Grillo captured his investigations on organized crime and violence in Mexico in three books that have been read around the world: "Blood Gun Money: How America Arms Gangs and Cartels" (2021), "Gangster Warlords: Drug Dollars, Killing Fields and the New Politics of Latin America" (2016), and "El Narco: Inside Mexico's Criminal Insurgency" (2011).

In addition, Grillo has published his stories in The New York Times, National Geographic, Time Magazine, The Houston Chronicle, and The Associated Press, among others, as well as podcasts and television series.

Grillo himself, 49, confesses to having had a fascination with the drug phenomenon from an early age. Growing up in a seaside town near Brighton, England, he experienced firsthand the addiction crises of the 1980s and early 1990s in the United Kingdom. He says he even had friends who died from heroin overdoses.

After studying Politics and History at the University of Kent, Grillo decided to follow his teenage desire to become a journalist. To do so, he traveled to Mexico in 2000, at the age of 27. He was interested in investigating the connection between drug consumption in first world countries and the trafficking that unleashes violence and destroys societies in Latin America.

"It seemed to me a bit like the narco issue was like a puzzle, something that doesn't make sense: you have a very compelling story, but it's not complete. Some pieces are missing and you have to find them," he said.

Determined to look for those pieces and put the puzzle together from the point of view of journalism, Grillo learned the trade from scratch. He began working at the English-language newspaper The News, a publication with a circulation of around 20,000 copies a day published by Novedades Editores in downtown Mexico City. Journalism figures such as Tom Buckley (The New York Times), Ted Merz (Bloomberg News), Laurence Iliff (The Dallas Morning News) and David Luhnow (The Wall Street Journal) have written for The News.

He then became a freelance reporter for The Houston Chronicle, which later, in 2004, gave him a full-time contract as their Mexico’s correspondent. He said he learned from then-Bureau Chief Dudley Althaus much of what he knows today about journalism.

From there he jumped to the Associated Press, where he worked until 2007. By then he had already mastered the sources of organized crime in Mexico, had covered the beginning of the war against cartels initiated by the former president of Mexico Felipe Calderon and had reported from drug violence hotspots, such as the states of Sinaloa and Michoacán. The following year, he began planning his first book.

"I was working for The Houston Chronicle when the violence started in Nuevo Laredo, on the Texas border, and I began to cover the start of a very strong escalation in the conflict," Grillo said. "Suddenly, I realized that this was a very strong moment, historically speaking, that was going to change and really do a lot of damage to Mexico during those years. That's when I started writing books."

Like all journalists who cover drug trafficking, Grillo has been exposed to the dangers that this implies in a country that is currently considered one of the most dangerous for journalists in the world. Most of the attacks against journalists come from organized crime. But also, as a foreigner, he faced extra obstacles.

"Once, when I was in Michoacán, I was accused of being a DEA [U.S. Drug Enforcement Administration] agent. I was covering the self-defense groups [groups of civilians who have taken up arms to protect themselves from the cartels] and a group arrived that were not self-defense groups, they were narcos. They had a lot of heavy weapons, they had AK-47s, grenade launchers, and they began to accuse me of being from the DEA," he said. “I have received threats to leave places, pressure from high-profile people, from public officials. I already have a 21-year [career]. I believe anyone that has put in that kind of time has experienced these kinds of things.”

Grillo has written three books on drug and arms trafficking in Mexico and Latin America.

However, he is aware that the real danger is not experienced by foreign correspondents or those who travel from the Mexican capital to areas of violence. It is the local journalists who must learn to live with danger permanently, and who suffer the onslaught of drug violence in Mexico.

"I am very aware that when I go to Reynosa, when I am with colleagues, we are traveling and working, but then we return to Mexico City. They [local journalists] live there. They can run into these people [the narcos] when they go to the supermarket, they see them in the street... [The narcos] know where [the journalists] work, where they live, so it’s another kind of pressure that is harder for colleagues who live in the provinces," he said.

The situation of his colleagues in the interior of the country is something that moves Grillo. But it’s also something that has helped him understand how organized crime works in relation to the control of the press in Mexico. It ends up causing censorship and news deserts in various regions of the country.

In border cities like Tijuana, Ciudad Juarez and Nuevo Laredo, the drug traffickers practically dictate what can and cannot be covered by the local news media, the journalist said. This has resulted in dozens of massacres, shootings and assaults that have taken place in the northern highlands of Mexico and in towns near the border, of which there is little or no record in news stories.

"This kind of super strong pressure from a violent de facto power is such a strong thing that exists in Mexico. Something similar happens in other countries, but the way it happens in Mexico, in few places is the situation that strong. This is a very hard challenge for journalists," he said. "I have seen drug dealers in those places with my own eyes, giving orders to journalists about how they can cover or not cover things. You see it and it is shocking. Those journalists in those places have to have a relationship with those crooks. They have to have almost their permission to be able to work."

Meanwhile, Mexico's current president, Andrés Manuel López Obrador, maintains a stigmatizing discourse against independent journalism, which includes calling journalists "conservatives" [as he calls his opponents], as well as publicizing the income of journalists who reveal corruption scandals in his administration. In contrast, López Obrador is soft on drug traffickers to the extent that some Mexican legislators have gone so far as to claim that the president has an alliance with criminal groups.

Nevertheless, Ioan Grillo believes that López Obrador's famous policy of "hugs, not bullets" towards criminals is nothing more than a campaign slogan and that the violence against journalists really dates back to previous administrations.

What Grillo does reproach López Obrador for is the total helplessness in which journalists live. His administration has left them practically at the mercy of organized crime. So far in 2022 alone, fifteen journalists have lost their lives violently in Mexico.

"Violence [against journalists] is a problem that many times comes from drug traffickers, from hitmen, although sometimes it also comes from hitmen [in alliance] with corrupt politicians, sometimes it also comes from police," Grillo said. “The bullets against journalists are not coming from AMLO's government, but as a government it should have a robust defense of journalism. Journalism is something crucial to democracy. The government and society should defend journalists and this is not happening.”

In his more than two decades of a career in Mexico, journalism has given Ioan Grillo great satisfaction. But what he values most are the different types of impact his books have had.

While his first book, "El Narco", has so far allowed him to receive messages from various parts of the world with feedback from readers, his most recent, "Blood Gun Money", about arms trafficking from the United States to Mexico, was quoted as a reference in the lawsuit the Mexican government filed in 2021 against U.S. arms manufacturers. They argued that their negligent business practices have unleashed the bloodshed south of the Rio Grande.

Receiving the Maria Moors Cabot Awards 2022 award next Oct. 11 means for Grillo a recognition of the effort he has made throughout his career. In previous years, the award has honored journalists such as Carmen Aristegui (Mexico), Jorge Ramos (United States), Mario Vargas Llosa (Peru) and Martin Caparrós (Argentina).

"Winning this award gives meaning to all this work, this journey I have followed in the past 21 years. As a journalist, you put your heart into it, you want to do things and it feels good when you write each story, each article, a book and people respond," he said. “One feels it’s been worthwhile, that I have achieved something. So for me it has a great meaning. I feel good about what I have done with the last 21 years of my life.”

Independent journalist Laura Castellanos (Mexico), investigative journalist Daniel Matamala (Chile), journalist and founder of Radio Ambulante Daniel Alarcón (Peru) and independent journalist Javier Garza Ramos (Mexico) complete the list of this year's winners.