By César López Linares and Emily Engelbart*

Mexico will close the year with a record number of journalists murdered. The organization Article 19 for Mexico and Central America has counted 17 press workers killed so far in 2022 in that country. In at least 12 of these crimes, the causes are directly related to the practice of the profession.

While international press freedom organizations demand justice, journalists agree that only the application of justice and the end of impunity can stop the bloody wave that threatens journalism in Mexico.

The most recent crime against a Mexican journalist happened as recently as Nov. 21 in the state of Veracruz. It was the murder of Pedro Pablo Kumul, a reporter for the digital media AX Noticias and broadcaster of the station Es Amor 105.5 HD.

According to local press reports, Kumul was shot several times while driving the cab he was working as a side job. The attack took place in the Casa Blanca neighborhood of Xalapa, the capital of Veracruz state. After the shots were fired, Kumul's vehicle crashed into a pole.

Just a day earlier, the disappearance of Francisco Hernández Elvira, coordinator of Radio Azúcar FM and president of the Club de Periodistas del Municipio de Isla, Veracruz, was reported. He was forcibly taken from his home by armed men who beat him, stole his computer equipment and kept him tied up and deprived of his freedom for 48 hours.

Article 19 issued a statement on both events and asked the Veracruz Attorney General's Office to investigate Kumul's murder under the Standard Protocol for the Investigation of Crimes Committed against Freedom of Expression, an instrument of the Federal Attorney General's Office (FGR, by its Spanish acronym) to determine if the aggressions against journalists seek to limit, undermine or affect the right to freedom of expression.

"Throughout the year, our regional office has documented that the press is attacked every 14 hours. So far, 12 journalists have been murdered because of their work. This situation places Mexico as the riskiest country in the world in which to practice journalism," Article 19 said in a statement dated Dec. 1.

Journalist Pedro Pablo Kumul was shot while driving the cab he was working as a side job. (Photo: Facebook)

UNESCO Director General Audrey Azoulay called on Mexican authorities to investigate Kumul's murder. The organization's Observatory of Murdered Journalists recorded 19 media professionals killed in Mexico this year. This list includes members of a radio station's technical staff killed in August in the state of Chihuahua, who are not included in other organizations' counts.

"I condemn the murder of Pedro Pablo Kumul and call on the authorities to investigate this crime. Attacks on media workers concern the whole of society, as they are an attack on freedom of the press, freedom of expression and freedom of information," Azoulay said.

The Inter American Press Association (IAPA) joined in condemning the incidents and urged the Mexican government to investigate quickly and thoroughly the murder of Kumul and the disappearance of Hernández in order to determine the motives for these crimes. With almost twenty media workers murdered and with little or no progress in the investigations, the organization assured that Mexico is already "the most dangerous country for the work of journalists."

"Crimes against journalists in Mexico are doubly serious, because in addition to the violence itself, most cases go unpunished," said the chairman of the IAPA's Committee on Freedom of the Press and Information, Carlos Jornet. “The perceived lack of interest on the part of the country's high authorities in resolving this serious situation is deplorable.”

The International Federation of Journalists (IFJ), the Federation of Spanish Journalism Associations (FAPE) and the National Union of Press Editors of Mexico (SNRP) also expressed their repudiation of the murder of Kumul and the other journalists who have been killed in 2022.

In a joint statement, the organizations demanded an urgent investigation into the crime against Kumul that considers the possibility that the journalist was murdered because of his journalistic work.

"Although the circumstances of this crime are not yet clear, the situation for journalists in Mexico is becoming more precarious and dangerous every day, given that so far this year there have been 17 murders of journalists and in very few cases have the culprits been identified," reads the statement.

With Kumul's death, Veracruz became the Mexican state with the highest number of journalists murdered this year, with four cases. The first murder of a journalist in 2022 in Mexico was that of José Luis Gamboa Arenas, general director of the digital newspaper Inforegio, who was stabbed to death on Jan. 10, in the Port of Veracruz.

Gamboa Arenas was followed by Yesenia Mollinedo Falconi and Sheila Johana García Olivera, director and reporter for the weekly El Veraz, respectively, who were gunned down on May 9 in the municipality of Cosoleacaque.

Two days after Kumul's death, the governor of Veracruz, Cuitláhuac García, said that the State Attorney General's Office already had a clear line of investigation into the murder and that they had already made some progress, including information on the alleged perpetrator. But as of that moment, there were no reports of people in custody.

During García's administration, which began in 2018, there have been eight murders of journalists in his state.

Journalism and freedom of expression organizations attribute the rise in violence against journalists in large part to the extremely high levels of impunity that prevail in Mexico. As of 2021, of the almost 3,500 investigations for aggressions against journalists carried out by the Special Prosecutor's Office for Attention to Crimes Committed against Freedom of Expression (FEADLE), only 28 of them had resulted in sentences against the perpetrators.

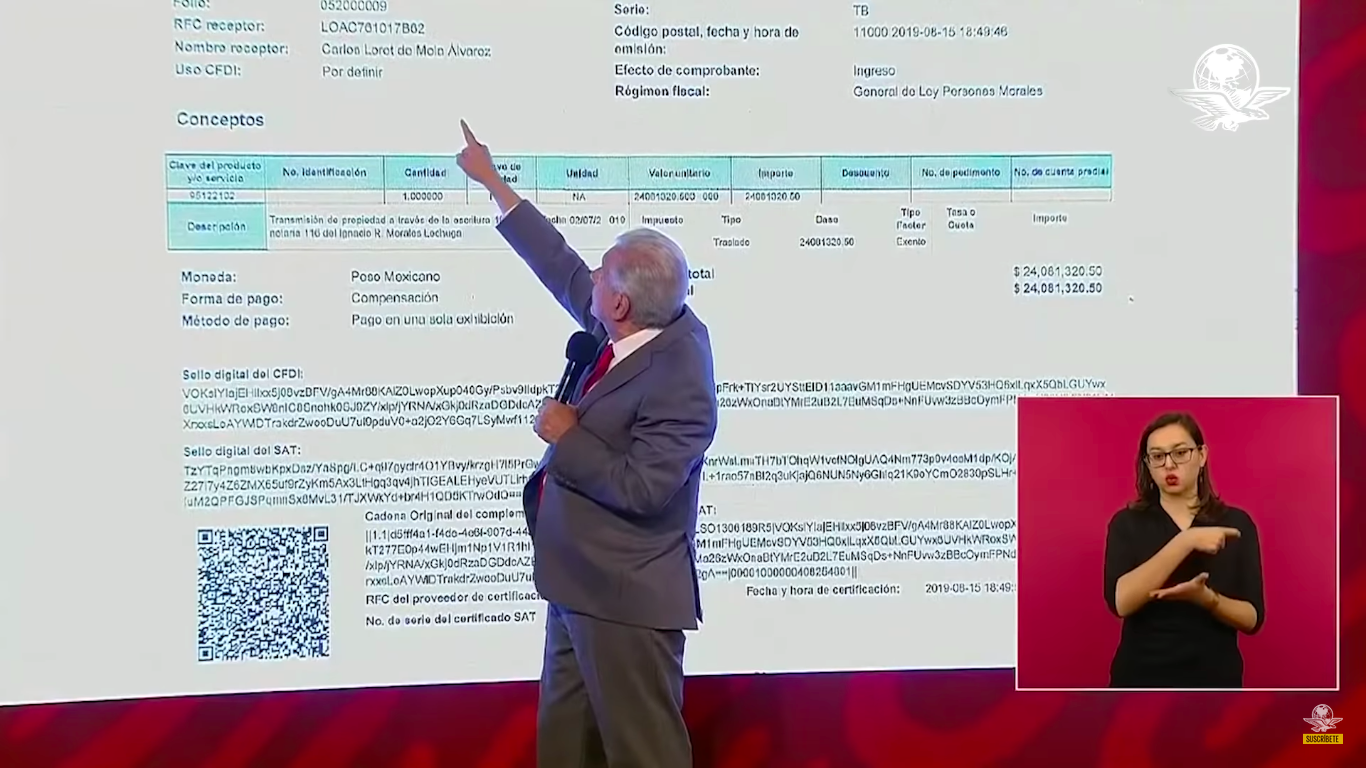

Mexico's President attacks and discredits the press at his morning press conferences. On several occasions he has disclosed the income and expenses of journalist Carlos Loret de Mola. (Photo: YouTube screenshot)

This means that the impunity rate for crimes against journalists in Mexico exceeds 99 percent.

“As impunity grows, and if crimes against journalists are not punished, there is incentive for those wanting to harm journalists,” Mexican journalist Javier Garza told LatAm Journalism Review (LJR). “Anyone who wants to kill a journalist [in Mexico] can be reasonably certain that they will get away with it because the last person did.”

American journalist and former Associated Press Bureau Chief for Mexico and Central America Katherine Corcoran said that the State institutions in Mexico designed to support and defend a free press are not active. That means that the press exercises its responsibility to expose government corruption and inform the public under no protection.

"[Journalists] say they keep putting out information because that is key to democracy,” Corcoran said to LJR in September on the occasion of the publication of her book "In the Mouth of the Wolf: A Murder, A Coverup and the True Cost of Silencing the Press.”

“So, that’s their purpose in continuing to investigate and write, also hoping that someday things will change," she added.

In addition to that, Mexican authorities, primarily at the federal level, have launched a campaign which threatens the validity and transparency of journalism. In 2022, Mexico’s president, Andrés Manuel López Obrador, raised the tone of his hostile discourse towards the country's media, using his morning press conferences to discredit, stigmatize and insult journalists that he considers opponents to his administration.

“This violates Mexico’s international principle of freedom of expression,” Sandra Rodríguez, a reporter and editor in the border city of Ciudad Juárez, told LJR. She added that authorities must investigate and punish crimes against journalists to ensure that this field can prosper and contribute to a harmonious and informed society.

“Only justice heals the social conflict resulting from the murders and sends the message that it is not allowed to commit them,” Rodríguez said.

Even though Mexico is one of the countries in Latin America with a State program for protecting threatened and at-risk journalists, this has been found to have serious problems and structural failures that thwart its proper functioning. This year, Reporters Without Borders (RSF) published a study that identified serious problems within the Federal Mechanism for the Protection of Human Rights Defenders and Journalists, which depends on Mexico’s Ministry of the Interior.

According to the study, the Mechanism requires urgent changes to ensure its effectiveness. Among the “important structural flaws” are dependence on ineffective institutions (such as the police, the army and the judiciary), risk analysis methodologies and protection plans that do not consider the particularities of journalistic practice, inadequacy of measures and delays in its implementation, and lack of human and financial resources.

This has resulted in a number of beneficiaries of this mechanism being killed or suffering assassination attempts. Some of the journalists killed so far in 2022 were under the protection of the Mexican mechanism, including Lourdes Maldonado, who was killed on Jan. 23 in Tijuana, Baja California, and Gamboa Arenas, killed on Jan. 10 in Veracruz.

But freedom of the press in Mexico is not only threatened by direct violence. Government advertising often represents a way of censorship to independent journalism, according to a study published by Article 19 last October. Many newspapers, local TV networks and other media outlets in Mexico are increasingly relying on government advertising because of the deterioration of their commercial business model, and that frequently becomes a tool of control.

"Billions of pesos have been used to maintain a culture of scheming and deception of the population through the purchase of space in the media and the expressions of various journalists throughout the country, with the intention of praising the government or government figures in office," reads the Article 19 report. "The perverse use of official advertising as a mechanism of censorship is a pillar of the structure of the Mexican political system, and the media have become accustomed to this."

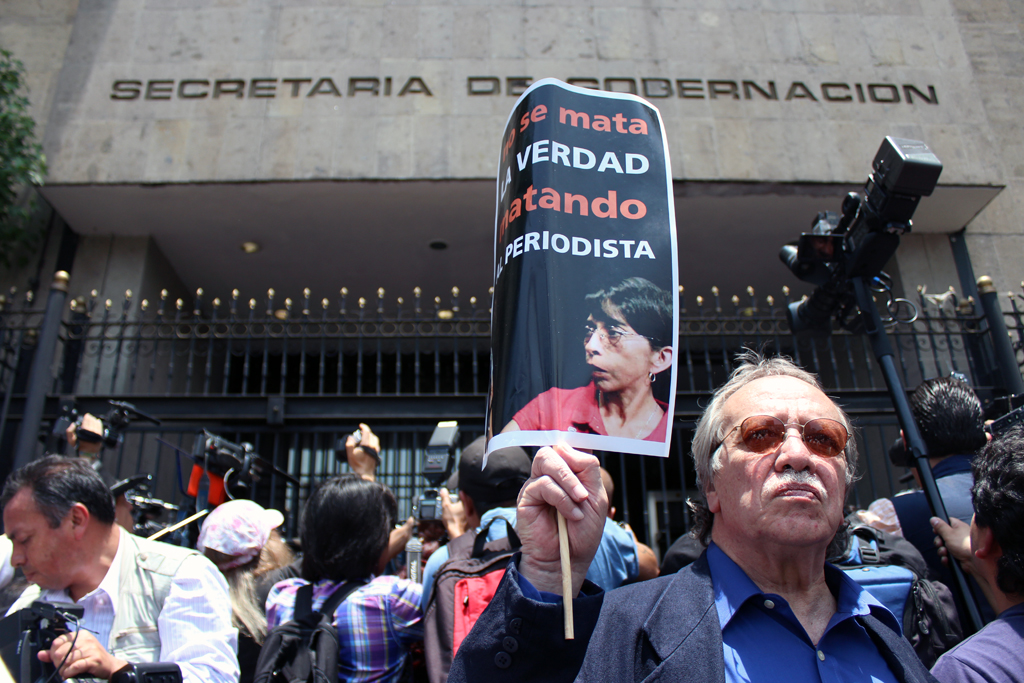

Several press members who were beneficiaries of the Mexican mechanism for protection of journalists, an instrument of the Ministry of the Interior, have been killed. (Photo: Cesar Mtz / Creative Commons)

Before the difficult landscape that Mexican journalism faces, journalists agree that their only hope is that the public get to understand the value of free press in their everyday lives and, consequently, they become a force that demands the government to protect journalists.

"We have to do a better job of explaining to our audiences what we do and why [journalism] is different from other types of information. [...] We must also explain to the public our role in maintaining freedom of expression," Corcoran said.

Garza pointed to how journalism communicates information to community members that pertains to their daily lives. Individuals need information on both global and local events. For example, he said, if the water is blocked-off in someone’s neighborhood or if there is an increase in gunshots in the neighborhood.

“People read about it and hear about it [threats against a free press] and say journalism is a dangerous profession. But I don’t know if they have actually weighed the value,” Garza said. “People need to know what happens when you lose independent journalism.”

When Garza and his colleagues received the first threats in 2007, he said he recognized that there needed to be measures taken to protect themselves and others working in the press. Doing so was a process of trial and error considering there was less research then available for reference.

“With Mexican journalists facing increasing danger, we need to be more aware of how to protect ourselves,” Garza said.

Some measures that he established include excluding the bylines of reporters for crime stories in order to protect their identity. Additionally, Garza said that it was best to avoid publishing explicit photographs, such as those showing bloody bodies on the street. Doing so could mean involuntarily being a messenger for a criminal to make a statement to the public.

Digital security measures are equally important, and everyone in the newsroom needs to be on the same page for it to be effective.

Frank Smyth, founder of GJS-Security, a U.S. company which provides training on journalistic safety, said to LJR that back in the late 80s, journalists had plaques to inform the public which news organization they worked for. Today this would be considered dangerous.

“Nobody tries to identify themselves as a journalist [now] because this would only invite threats,” he said.

Javier Garza Ramos believes that today more than ever, with crimes against journalism on the rise, journalists must be aware of how to protect themselves. (Photo: Courtesy of Columbia University)

Smyth recommends that journalists watch the “Hostile Environment and First Aid Training,” which is available on YouTube. Created by the International Women's Media Foundation (IWMF), the training prepares journalists to report with precautions in an increasingly dangerous field, especially for women. Additionally, it can improve journalists’ situational awareness, self-defense and first aid skills.

On social media, journalists need to be cautious of their posts, ensuring that the information posted is not too revealing of details such as location or travel plans, Garza said. It could also be useful to have a phone for personal purposes and another exclusively for work purposes and when reporting in the field.

Garza is the editor of the e-book “Protection of Journalists: Safety and Justice in Latin America and the Caribbean,” published in September of this year. The e-book is a compilation of 14 stories that were published on LJR from Dec. 2021 to July 2022, focused on how journalists can keep safe while covering protests and violent conflicts. It also talks about the development of protection mechanisms for journalists in Latin America and the investigation and prosecution of violence against journalists.

The e-book, funded by UNESCO’s Global Media Defense Fund, can be downloaded for free in English, Spanish or Portuguese from the JournalismCourses.org digital library.

* This story was produced as an assignment for the class “Reporting Latin America,” at the University of Texas at Austin School of Journalism and Media.

Emily Engelbart was born in Houston, Texas. She is a Journalism student with a minor in Spanish and a certificate in Environment & Sustainability at the University of Texas at Austin. Emily likes to report on topics relating to the environment and science in addition to current events in the US and Latin America.