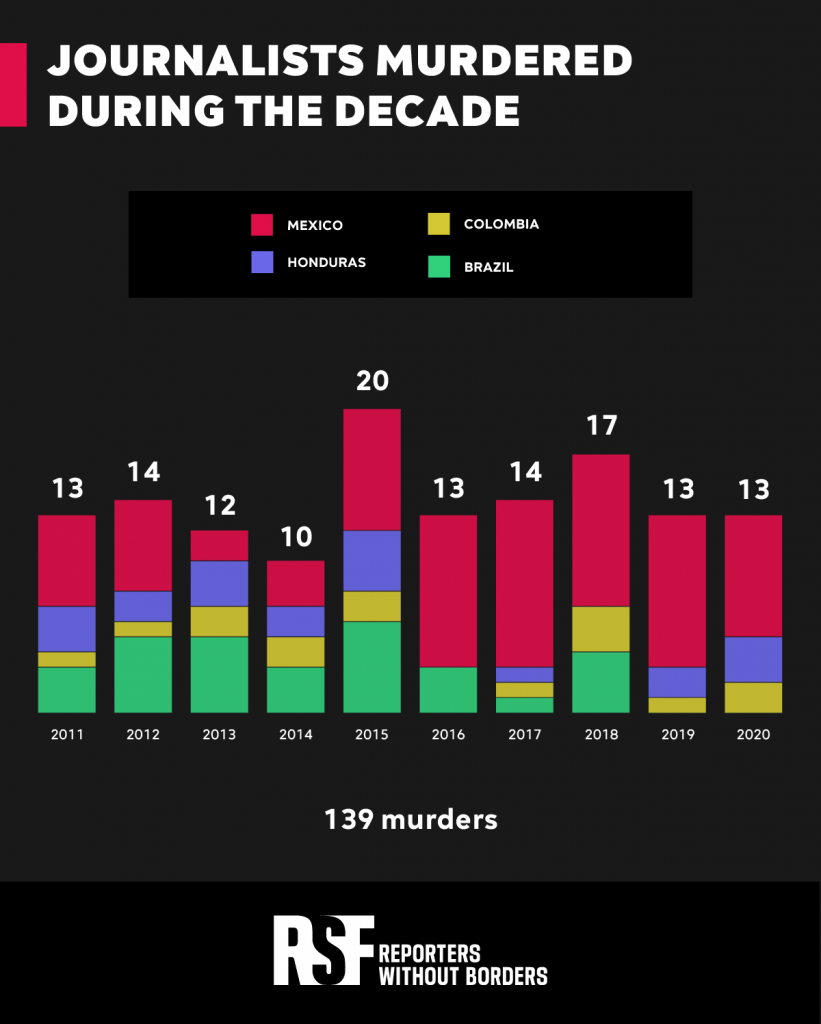

Journalistic coverage and investigations of politics, corruption and organized crime carried out in small and medium-sized cities in Brazil, Colombia, Honduras and Mexico were at the root of 139 murders of press professionals that took place between 2011 and 2020, recorded by the organization Reporters without Borders (RSF, for its acronym in Spanish). According to RSF, half of these people had reported threats.

The information was collected within the framework of the development of the project “In Danger– Analysis of journalist protection programs in Latin America,” carried out by RSF with the support of UNESCO through the Global Media Defense Fund, which will take place over 12 months.

Although at the beginning of the project there was no plan to carry out thematic publications before the final report, the data found so far are important enough not to wait a few months, Bia Barbosa, project coordinator, told LatAm Journalism Review (LJR).

“When we started the project, there was not even a forecast of making publications during the production process of the investigation, but […] when we started to study the context and the risk situation a little – the profile of the journalist, that of the communicator most vulnerable to the more serious violence, which is murder – we found it interesting to publish,” Barbosa said.

Infographic from Volt Data Lab and RSF about journalists killed in the last decade in the four countries with protection mechanisms and who are part of the RSF project. (Courtesy)

This profile, for example, shows that the victims are mostly men (93% of the cases) and that they lived in relatively small cities.

“The statistics do not fit the popular image of an investigative journalist who works for a major newspaper based in a capital city, who is killed for having reported information of national importance,” the RSF publication reads. “To the contrary, most of the journalists murdered in Brazil, Mexico, Colombia and Honduras in 2011-2020 lived far from major urban centres, often worked in precarious economic circumstances, contributing to several media organisations, and covered issues that directly affected local officials and inhabitants.”

The study also indicates that in 92 percent of the cases, journalists were the “target,” that is, they were in the crosshairs of their attackers. Only 10 of the 139 cases occurred during risky coverage. In these cases, the journalist was shot without necessarily being the target.

Precisely because they are clear objectives, most of the crimes – 58% – share the way in which they were carried out: journalists were followed by their attackers and the crime was carried out by professional murderers, the publication said. In these cases, journalists were attacked near their offices, in their homes, or on the way between their places of work and home.

One in four journalists, especially in the case of Mexico, were abducted before being killed. Most of the corpses were found with signs of torture and in some cases even mutilated.

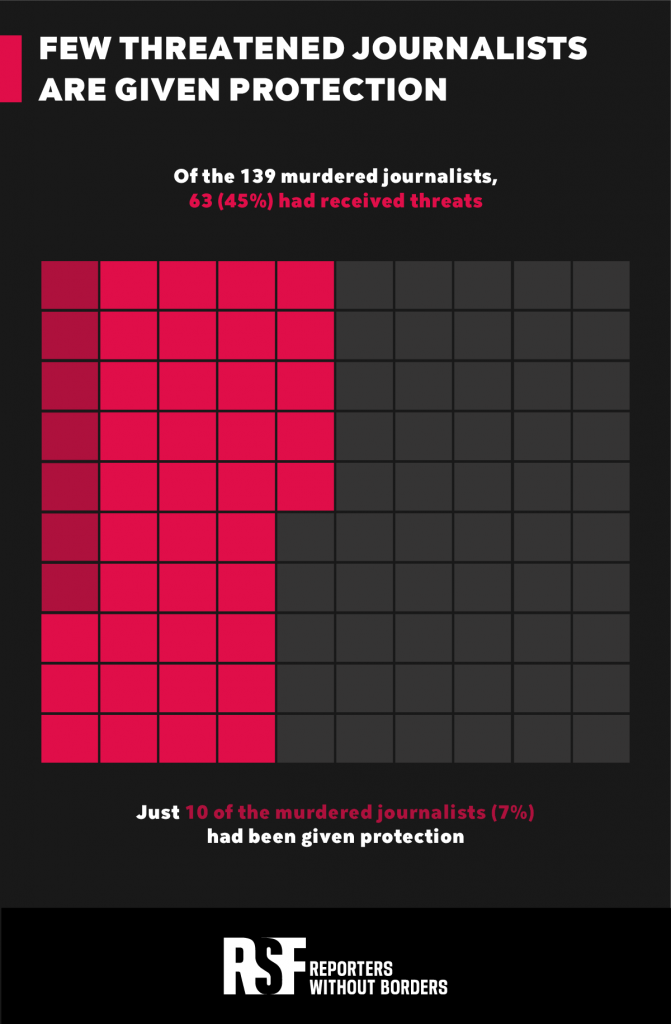

One of the most relevant findings that is directly related to the objective of the project is that at least 45 percent of the victims “had reported receiving threats and had made them public – either in the media they worked for, on their social network accounts, or directly to local security forces,” according to the RSF publication.

However, only 10 of them received some type of protection from the State, that is, 7.2 percent of the total and 16 percent of those who had been threatened.

“There are [cases of] journalists who were under the protection of mechanisms […]. It happened in Mexico, it happened in Colombia, they were under protection and they ended up murdered. So it is certain that there are problems, there are things to face. The idea is to analyze these more structural deficiencies,” said Barbosa, who stressed that for now the need to strengthen the mechanisms is clear.

The region’s protection mechanisms under the magnifying glass

Analyzing the situation of the mechanisms for the protection of journalists in Brazil, Colombia, Honduras and Mexico with the purpose of offering practical recommendations for their strengthening is the main objective of the project “In Danger– Analysis of journalist protection programs in Latin America,” Barbosa explained to LJR.

For the final report, the regulatory frameworks – laws and decrees of the four countries –, reports from international organizations, civil society and even the same mechanisms, will be analyzed. According to Barbosa, interviews will also be conducted with the three main groups: beneficiaries of the programs; managers and public officials as well as the team that is part of the mechanism; and civil society organizations that monitor protection programs or are part of them, in the case of countries that allow this participation.

“In the end, we are going to produce this report and also carry out a series of actions and political advocacy activities to present the results to governments, public authorities in general, and international organizations so that we can get some of these measures and recommendations implemented,” Barbosa said.

For the project coordinator, working with the public policy approach is what will allow a better understanding of the deficiencies of the mechanisms as well as the different particulars of each one. For example, Brazil has had a protection mechanism since 2005, but journalists were not included until 2018. However, she also understands that the “Latin American context” unites them and therefore allows these comparisons to be made.

“The idea is to contribute so that [...] not only so that the mechanisms are strengthened, but so that other countries that come [later] to develop protection mechanisms can learn from the successes and errors of the mechanisms that are already in operation,” Barbosa explained.

Turning what was found in the project into concrete actions is precisely one of the biggest challenges. The team knows that for years the mechanisms have been under scrutiny not only by local, but also international, organizations.

Infographic from Volt Data Lab and RSF shows journalists who were threatened before being killed. (Courtesy)

In the case of Mexico's mechanism, the second to be implemented in the region, due to the levels of violence against journalists experienced in the country, the Office in Mexico of the United Nations High Commissioner for Human Rights presented an extensive report with 104 recommendations to strengthen the mechanism in 2019.

“Probably we are not going to find anything unprecedented in the matter of problems of the Mexican mechanism that the United Nations Commissioner did not find in 2019. But, what happened in the last two years since this super-detailed analysis? Why was it not possible to implement the recommendations that were made two years ago? So, we are going to investigate, even the recommendations, and work with more practical measures that can actually be implemented,” Barbosa said.

In Colombia, the first mechanism in the region is also subject to criticism. The lack of a quick response to threats against journalists, as well as the lack of commitment from the government, according to some local organizations, have affected its efficiency. In 2017, Colombia’s Press Freedom Foundation (FLIP), which promoted the creation of the mechanism in 1999 and was part of the mechanism's Risk and Measures Recommendation Committee for 16 years, decided to withdraw because it said its contributions were dismissed at the moment of protecting journalists.

Something similar happened in Honduras. The National Association of Journalists reported it was withdrawing from the mechanism due to the large number of murders and assaults and the impunity surrounding these crimes.

In order to achieve more effective changes, the RSF team presented the project to mechanism representatives from the beginning, thus guaranteeing their active participation and commitment.

“Because the idea is not to just make the criticism – we are going to do all the critiques that we have to do–- but the idea is actually to make changes in the end. And for this, we need the commitment and goodwill of the mechanisms, from officials to the coordination of the protection program,” Barbosa said. "So, we presented the project to the mechanisms and they all thanked us for the initiative and signed a commitment of 'well, let's go, let's work together.’”

Guilherme Canela, head of UNESCO’s section on Freedom of Expression and Security of Journalists, told LJR that the entity has worked for years to promote different mechanisms so that States can comply with their obligations to prevent attacks, protect journalists and prosecute aggressions against them. The purpose, according to Canela, is to foster a more favorable and safe environment for practicing journalism, which has been promoted with the Global Media Defense Fund.

“However, there is no doubt that there is still a great space to reinforce the operation of these protection mechanisms and the commitment of government, judicial and civil society actors with their implementation,” Canela. “The information collected by the RSF study is relevant to determine where these mechanisms could be failing, identify what are the lessons learned and the main challenges or limitations that have hindered their full or successful implementation. Therefore, having this information is of great importance to propose specific adjustments, solutions and recommendations for the specific context of each mechanism, and thus increase the safety of journalists.”

Although women journalists are murdered less, comparatively, the project seeks to analyze the security situation of this specific group and the protection measures granted.

“In terms of the number of murders, for example, women are not the main victims. But, when we look at threats and even in the digital environment, which is a more current problem in terms of threats for journalists and communicators than, for example, for human rights defenders in general, women are the main victims,” Barbosa said.

The final report will have a special chapter to analyze what the specific needs are and why it is necessary to guarantee a gender perspective in public policy. An important perspective not only when evaluating cases and their risk analysis, but also in what type of protection measures should be offered to women journalists. For example, the issue of forced displacement, which tends to be tougher for female journalists with young children, Barbosa explained.

At the moment, a large part of the project has been carried out virtually and with the help of RSF correspondents in each country. The first interviews have already started and a first questionnaire has been sent to the protection mechanisms. The project that began in February 2021 will end in the first months of 2022. Barbosa does not rule out thematic publications throughout this year, such as the one recently made on the profile of the victims, if relevant data is found.