“We joke that if a reporter were to come from mars, know Portuguese, and read the manual, he would be able to get by the elections”, said Angela Pimenta, who is the editor of the project and director of operations of Projor

Smith said that reporters are having to adapt to a new reality, trying to come up with different ways that simulate in-person conversations with voters

After a little more than eight months of preparation and arriving at agreements between organizations that support the new data verification initiative in the region, Uruguay has joined the fight against misinformation with the launch of fact-checking site Verificado.uy on July 22.

Each May 3 is a global celebration of press freedom and its importance to society. For this year’s World Press Freedom Day (WPFD), journalists and press freedom advocates will focus on media and elections, as well as the role of media in peace and reconciliation

Before and during the Brazilian presidential election that took place on Oct. 28, journalists were the subject of physical, verbal and digital threats and aggression.

Seven Brazilian verification initiatives presented a letter with suggestions of concrete measures that the Superior Electoral Court (TSE, for its initials in Portuguese) can take to help them fight general disinformation related to the country's elections, whose second round happens on Oct. 28.

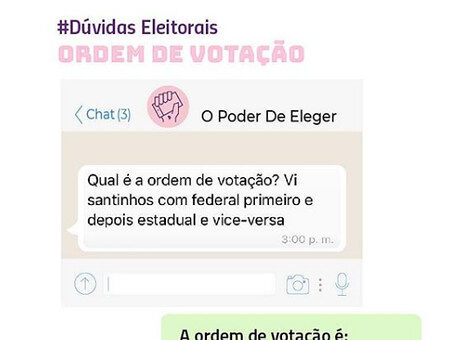

WhatsApp has 120 million active users in Brazil, according to what the company reported in July this year. This number is equivalent to more than half of the Brazilian population, estimated at 208.5 million people.

On Oct. 7, the Brazilian electorate goes to the polls for general elections marked by the intense dissemination of rumors and fraudulent news on social networks, also fomented by the public’s distrust of the press. In this charged political and media environment, journalists have been consistently targeted for doing their investigative and reporting work.

The year 2018 has posed several challenges for fact-checking initiatives in Brazil. In addition to general elections permeated by intense political polarization and the new weight of social networks in the dissemination of rumors, fact-checking professionals are also faced with the distrust of the public, still in doubt about the role of fact-checking in the Brazilian media environment.

In 2018 several Latin American countries will see presidential elections, and with them, the risk of widespread misinformation caused by fraudulent news. In Brazil, concern about the problem has moved public authorities, and within four months of the election, the Superior Electoral Court has made its first decision regarding the fight against fraudulent news in the electoral context.

Just after the controversial May 20 presidential elections, a regulatory agency for the government of Venezuela is using a controversial new communications law against the website of one of the country’s most widely circulated newspapers.

During the highly criticized Venezuelan presidential elections on May 20, monitors of freedom of expression recorded physical attacks on journalists as well as intimidation. It’s more of the same for a community of journalists that has been threatened physically, in the courts and online while covering growing political and societal unrest in recent years.