"We have not had the killing of journalists beyond what circumstances have caused."

This is what Mexico’s President, Andrés Manuel López Obrador, said less than a month before leaving office in a speech celebrating his achievements.

However, data from press freedom organizations paint a starkly different picture. During the six-year term that ends on Oct. 1, press freedom and the safety of journalists faced numerous challenges, including the murders of dozens of media workers.

Despite campaign promises to respect freedom of expression, López Obrador's government was marked by an alarming rise in attacks against journalists, as well as a controversial strategy for dealing with the media.

The same day López Obrador assumed the presidency of Mexico, Dec. 1, 2018, the body of journalist Jesús Alejandro Márquez Jiménez, editor and founder of the outlet Orión Informativo in the state of Nayarit, was found lifeless.

Nearly six years later, Alejandro Martínez Noguez, who lost his life on Aug. 4 in the state of Guanajuato, may be the last journalist killed under the outgoing administration. Martínez Noguez, who ran a Facebook-based outlet covering crime in the city of Celaya, had been under police protection due to previous attacks.

Journalists in the state of Guerrero protest the murders of colleagues in 2023. (Photo: La Prensa Gráfica, CC BY 2.0, via Wikimedia Commons)

The number of journalists murdered during López Obrador’s term stands at 47, according to data from independent media watchdog Article 19. This figure is the same as that of his predecessor President Enrique Peña Nieto.

The overwhelming majority of journalists killed during this administration had one thing in common: they worked for small local outlets, many of which were social media-based personal projects in remote regions dominated by organized crime. The deadliest year was 2022, with 13 murders, while the most violent states were Sonora, with seven cases, and Veracruz, with five.

Impunity reigned. According to the 2023 Global Impunity Index by the Committee to Protect Journalists, or CPJ, Mexico ranks seventh among countries with the highest number of unresolved killings of journalists.

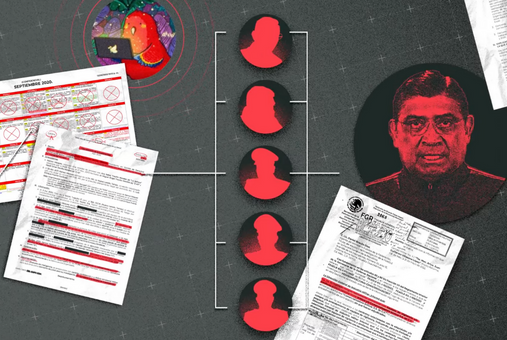

Here is a list of journalists murdered during López Obrador’s administration, according to Article 19’s tally. The numbers differ from those of other organizations due to varying criteria in considering journalism as the motive for the killings.

Mexico also leads the list of missing members of the press. By April this year, Reporters Without Borders (RSF) recorded 31 journalists who had disappeared in Mexico since 1989. This accounts for nearly a third of journalists missing worldwide.

During López Obrador's term, at least 10 media workers were reported missing, according to RSF’s tally. Of those, five are still missing: Jorge Molontzin Centlal, Pablo Felipe Romero Chávez, Roberto Carlos Flores Mendoza, Juan Carlos Hinojosa Viveros, and Alan García Aguilar.

According to Article 19, at least four journalists are still missing by the end of the current administration. (Photo: Article 19, CC BY 2.5 MX, via Wikimedia Commons)

Molontzin Centlal, a native of Chiapas, disappeared on March 10, 2021. He lived in the state of Sonora, where he worked as a reporter for Confidencial magazine in the city of Caborca.

Also in Sonora, Romero Chávez disappeared on March 25, 2021. After a three-year break from journalism, he had returned to work as a crime reporter at a radio station in the port city of Guaymas and for the newspaper El Vigía.

Flores Mendoza was reported missing on Sept. 20, 2022, in the town of Comitán de Domínguez, Chiapas, after being intercepted while driving his car. Flores Mendoza ran the Facebook page Chiapas Denuncia Ya, where, days before his disappearance, he had posted information about an alleged internal struggle within a criminal group, according to press reports.

The most recent disappearance is that of Hinojosa Viveros, a photographer and editor of the digital outlet La de 8 News in Veracruz. Hinojosa Viveros was last seen on July 6, 2023, in the town of Nanchital, where he lived.

Article 19’s list also includes Alan García Aguilar, who was abducted by a criminal group on Dec. 25, 2022, alongside two other men identified as Fernando Moreno Villegas and Jesús Pintor Alegre, in the region known as Tierra Caliente in the state of Guerrero.

On Jan. 7, 2023, a video was posted on the Facebook page Escenario Calentano, which García Aguilar had founded in 2018 to publish content about organized crime. The video showed García Aguilar and Moreno Villegas handcuffed and barefoot, saying they were “paying the consequences for their publications.”

Moreno Villegas and Pintor Alegre were released on Jan. 11, but García Aguilar’s whereabouts remain unknown.

While violence targeted members of the press in Mexico, López Obrador's administration officials became the main perpetrators of attacks and harassment against journalists.

López Obrador’s morning press conferences, considered the centerpiece of his communication strategy, were the primary stage for attacks on the media and journalists, and for spreading disinformation during his term. Article 19 documented at least 179 aggressions against journalists and media outlets in his “mañaneras,” as the conferences held daily from the Presidential Palace became known.

Press freedom organizations found Lopez Obrador developed a stigmatizing discourse against the press, frequently labeling them with insults such as “journalism mafia,” “hypocrites,” “elite press,” “conservatives,” and “corrupt.” Article 19 found this rhetoric often created a ripple effect among local and state authorities, and even citizens.

Judicial harassment was another form of attack during López Obrador’s term, with 158 legal cases filed against journalists or media outlets in civil, criminal, or administrative courts, according to the report. Of those cases, almost two thirds were initiated by authorities or individuals connected to public officials.

Carlos Loret de Mola was one of the journalists facing legal action and was also one of the most openly attacked by the president. Pío López Obrador, the president’s brother, sued Loret de Mola and the digital outlet Latinus for moral damages, demanding $400 million pesos (about $20.6 million USD) in damages after the publication of reports exposing alleged acts of corruption.

In June this year, Mexican tax authorities opened investigations into the bank accounts and properties of Latinus, Loret de Mola, his wife, and actor Victor Trujillo, who has also criticized López Obrador on the platform.

Journalist Carlos Loret de Mola was sued by the brother of the President of Mexico after revealing videos of alleged acts of corruption. (Photo: Screenshot of Latinus on YouTube)

“Constant attacks prevent journalists from carrying out their work freely and fully, which severely weakens the information they disseminate, undermines public debate, and, consequently, democracy,” the report says.

Another way in which López Obrador exerted harassment was by disclosing personal and financial information of journalists and critics. Loret de Mola was among those affected when, in February 2022, the president displayed a graph showing his alleged income, without citing a source. This occurred after Loret de Mola released a report about the luxurious lifestyle of López Obrador's eldest son.

In February of this year, during another “mañanera,” the president revealed the phone number of The New York Times journalist Natalie Kitroeff, who had reported the U.S. government had investigated alleged links between López Obrador and drug cartels.

In both Loret de Mola's and Kitroeff's cases, the National Institute for Transparency, Access to Information, and Personal Data Protection, or INAI, launched investigations against the president. In Loret de Mola’s case, the agency ordered the Presidency of the Republic to sanction López Obrador for violating the journalist’s personal data. However, no sanctions were imposed, according to press reports.

INAI was included among the autonomous bodies that López Obrador seeks to dismantle through a legislative initiative currently being debated in the Mexican congress, along with a package of reforms the president aims to have approved before leaving office.

More than 3,400 aggressions against the press were documented during López Obrador’s presidency, according to the Article 19 report “Pending Rights.” The most frequent types of attacks were intimidation and harassment, threats, and the illegitimate use of public power. Almost half the attacks were perpetrated by government officials.

"You can now speak freely on the phone. There are no more ‘birds on the wire,’” said López Obrador in Dec. 2018, just days after assuming the presidency, to promise his government would not spy on journalists and activists, as had happened under the administration of his predecessor Enrique Peña Nieto.

However, investigations by The Citizen Lab, a cybersecurity and human rights monitor at the University of Toronto, determined that during Peña Nieto's presidency, cases of espionage occurred using the Pegasus spyware, developed by the Israeli company NSO Group. At least 25 victims were targeted, including journalists Carlos Loret de Mola, Carmen Aristegui, Rafael Cabrera, Sebastián Barragán, Daniel Lizárraga, Salvador Camarena, Andrés Villarreal, Ismael Bojórquez, and Griselda Triana, the last two being the colleague and wife, respectively, of journalist Javier Valdez, who was murdered in 2017.

Despite López Obrador's commitment, espionage cases continued during his administration. The investigation “Espionage Army: Out of Control,” conducted in 2022 by the organizations Artículo 19, Red en Defensa de los Derechos Digitales (R3D), and Social TIC, revealed at least three cases of surveillance using Pegasus.

One of the cases involved journalist Ricardo Raphael, while another targeted a member of the digital media outlet Animal Político, whose identity remained anonymous. According to the investigation, these cases occurred, during López Obrador's presidency from 2019 to 2022.

The president claimed that no new contracts were signed under his administration for acquiring remote monitoring software. However, a 2022 leak of documents from the Secretaría de la Defensa Nacional, or Sedena, attributed to the hacker group Guacamaya, revealed the Mexican Army had signed a contract in 2019 with one of the distributors of Pegasus.

According to the investigation “Espionage Army”, Sedena initially denied the existence of contracts to acquire the spyware but later admitted they existed, though the information was classified for five years due to alleged national security concerns.

The investigation “Espionage Army” revealed at least three cases of spying on journalists with Pegasus during López Obrador's six-year term. (Photo: Screenshot of ejercitoespia.r3d.mx)

“They [the Army] conduct intelligence work, not espionage, which is different,” López Obrador said when questioned about the findings.

In a subsequent report from “Espionage Army” in 2023, it was revealed that surveillance of journalists and activists took place within a secret structure at Sedena’s facilities, known as the Military Intelligence Center. It also disclosed the monitoring of Raphael and the journalist from Animal Político occurred with the knowledge and approval of Defense Secretary, Luis Crescencio Sandoval.

The evidence linking the military to these espionage activities alarmed freedom of expression organizations, given the significant power the military accumulated. Not only did they gain dominance in public security tasks, but also in intelligence operations. Additionally, Lopez Obrador granted them authority over customs control and public infrastructure projects.